CHAPTER I

THE QUEEN'S ARMS

Selborne, Hampshire

THE steamer that goes between Havre and

Southampton was just rounding the Isle of Wight, when three

dejected-looking young women stepped out of a deck cabin into the clear

air of the July morning. They had survived and endured with bitter

complaints one of those noted passages which the English Channel has

the monopoly.

The waves had dashed furiously all night

long against the small ship; it had groaned and shivered in response,

and these three women had groaned and shivered in concert with each

creaking timber.

They had denied themselves the pleasure

of longer wanderings in lovely France for the sake of a short tour

through rural England. My persuasive tongue it was which had brought

them to this decision and over the rough waters of the Channel. I had

therefore not only suffered with seasickness myself through all the

wild night, but had joined to physical pain the mental agonies of

responsibility and remorse. The bright sun now above, smooth water

around, and green land within sight dispelled regrets and reproaches;

we met with smiling faces.

"Here comes Polly, as fresh and rosy as

the morn," exclaimed the chief Invalid, as the youngest of our

quartette appeared smiling at the gangway door.

"She must get us some coffee."

"She can't," answered the blooming

Polly. "There is neither tea nor coffee fit to drink on board. I have

tried both. A jovial old Englishman suggested beer, but as I did not

wish to spoil my record as a good sailor, I declined that morning

beverage."

"Here are some tablets of chocolate, one

for each."

I had forgotten in my despairing mood

that I had wisely provided food for this very emergency.

"Must all these other poor seasick

creatures travel to London without food?" sighed the sympathetic

Invalid. The Southampton docks being now within sight, we lost interest

in everything but the business of landing. We seized our bags and left

the boat as rapidly as possible.

Pennies liberally distributed, and the

simple formalities of the English Customs passed, we crossed the

dockyard and turned down the street toward the Great South Western

Hotel, and breakfast! Our normal appetites had returned with increased

vigour after we felt firm ground beneath our feet. We were followed on

our way by our small luggage, piled upon a hand-cart and drawn by a

red-headed porter.

Breakfast soon waited our pleasure in

the sunny dining-room. Toasted muffins, hot coffee, marmalade, and all

the various accessories of that most comfortable English meal, while

the proprietor of the hand-cart went away murmuring because, having

demanded three shillings, Polly gave him but half that amount,

– quite enough for his service. Such encounters are sport

for Polly. We have constituted her Treasurer and Financier-in-chief of

the party. She proved so able in France, that we have voted unanimously

to continue her in office on our present journey. To speak truly, she

alone of the entire quartette does not consider arithmetic simply a

matter of fingers.

The cheery breakfast so completely

restored the entire party that the Invalid and the Matron began to make

anxious inquiry about our immediate destination. "Just take us where

you like, and surprise us," both the Invalid and the Matron had

entreated when they constituted me guide of the party, and now two cups

of coffee had excited them to indiscreet curiosity.

The Matron, be it told right here, is

not so venerable as the name would imply. She is young, but owes her

title to the possession of a husband. He is concealed somewhere in the

mazes of the United States, engaged in the most fascinating sport of

money-making, while she assumes, as a consequence of his existence, a

dignity we spinsters do not presume to imitate. She also has an excuse

to retire and write letters to the absent gentleman whenever she feels

bored in our society.

"You promised to ask no questions," says

my lieutenant, the Treasurer. "The tickets are in my pocket, the

luggage is labelled, and the train will be ready in half an hour to

bear us away to Alton, where we are to take carriage for Selborne."

"Gilbert White's Selborne?" inquires the

Invalid, in a whisper. Before any one bothers to answer, we are rolling

away from Southampton, past Winchester, to Alton. The Treasurer puts us

into third-class carriages; she insists that two cents a mile is quite

all we can pay. The Invalid and the Matron felt at first inclined to

rebel at the economy, but finding third-class so much better than they

expected, they spend half the time of the journey talking about it.

One of the eccentricities of the British

railway system is the aversion the officials display to calling out the

name of a station. At the extreme end of each small platform, hidden

among brilliant invitations to "Use Pear's Soap " or "Take Beecham's

Pills," the name of the town is shyly concealed by a modest gray sign.

My party almost refused to follow me, when I began to pull down the

bags at Alton.

"How do you know where we are?" asked

the Matron.

There was no time to explain, so I

bundled her on to the platform and quieted her fears by introducing her

to the host of the Queen's Arms, who sat on the box of his wagonette

waiting to drive us to Selborne. We had sent him a telegram from

Winchester.

The town of Alton saves itself from

hopeless dulness only by the pretty curve its High Street describes. I

have read somewhere that Mrs. Gaskell was building a house in Alton

when she died, yet the place itself possesses no visible attractions. A

barrel-bodied, piebald horse, mounted on a rolling platform by four

sticks of legs, and hanging in a most perilous and unnatural position

outside a quaint shop, excited the Matron so profoundly that she vowed

that Alton was a veritable picture-book town, but her imagination is

broad.

Alton, situated in the centre of a

hop-growing region, is a brewing town. The solemn brick Georgian houses

look comfortable and ugly. Public houses, mere drinking-places, supply

all the picturesque element by their names: the French Horn, the Hop

Poles, the Jug of Ale, and the pretentious Star, "patronized by

Royalty."

The green once passed, and the homely

little town behind us, we become aware of the charm which induced Mrs.

Gaskell to choose Alton as a dwelling-place. The road branches where we

leave the last houses; one way leads us over low hills to our

destination, the other is a shaded road to Chawton, where lived Jane

Austen's brother, who inherited the manor-house, and the cottage in

which that gentle authoress spent the last years of her life.

Over the hills and far away goes the

road to Selborne, past fields where festoons of the hop-vines make

bowers of green. The highway winds up and down for five miles through

copse and farm lands. We see noisy rooks gleaning the fields, and men

ploughing with oxen; these last a rare sight in England. From the high

points of the road we look down into the sunny valley on the little

village of Chawton, and see the noonday smoke rising from the cottages.

At the top of the last steep hill on our drive, the long, low ridge

before us is pointed out to us as the "Hanger," and nestling at its

base lies the village of Selborne.

None of the party, excepting the writer,

has ever before seen an English village inn. They are at first inclined

to be disappointed because "The Queen's Arms" does not more exactly

resemble the comic opera counterfeit. When the bedrooms are assigned

us, the Matron discovers we fill the house.

"A whole inn to ourselves! Could

anything be more perfect!"

We reach our bedrooms and our long

narrow sitting-room by an antiquated staircase, shut off with a door at

the bottom from the neat old-fashioned bar. At the "Queen's Arms" the

bar, true to its name, is a broad shelf of wood, lifted or put down at

the will of the innkeeper's pretty daughter, when she serves cider, or

more potent drinks, to thirsty customers. To be invited into the family

parlour, behind the bar, is the privilege of only the chosen few.

Our private stairway is decorated with

stuffed birds and porcelain tableware, all brilliant in colour but more

or less dilapidated by age and use. Our sitting-room possesses as an

object of luxury a grand piano, dating from the very earliest days of

grand pianos. Like many ancient singers, both its voice and most of its

teeth are gone, but, unlike a prima donna, its exterior has grown more

beautiful with each passing decade. The old French mahogany case is a

joy to the artistic eye. The mantel ornaments are frankly from

Birmingham, and bear the stamp of the peddler's pack; all ugly and

useless. The pictures evidently came from the same source many years

ago. A hideous coloured landscape and an impossible Joan of Arc

disfigure the quaint, venerable walls, but the lattice window opens

wide on a scene so lovely that the interior of the room is forgotten.

Behind the diamond panes a gay

flower-garden stretches away to broad fields, and past these are the

dark beech-trees in the long, narrow valley of the Lythe.

Our travel-stimulated appetites do full

justice when lunch appears. It consists of chops, new potatoes, and

gooseberry tart, an excellent specimen of many of the same kind which

we are destined to consume before our trip comes to an end.

"The sweet simplicity of English cooking

probably had its origin when salt was highly taxed," observed Polly

with solemnity, as she emptied the salt-cellar on her plate.

"We did not come here to criticize the

food," interposed the Invalid, sternly. "Still, salt is a healthy

condiment; you might ring for some more." Polly has not left a single

grain in the diminutive glass dish.

The village of Selborne has but a single

street which is honoured with a name, Gracious Street. It is now little

better than a deep, shady lane, which skirts the park of that

comfortable small estate where, more than a century ago, lived Gilbert

White, the naturalist, the genial writer of those graceful letters

which delight the reader of "The Natural History of Selborne." In the

time of Gilbert White, Gracious Street was the road through Chawton to

Alton. It was then even more of a lane than it is to-day, and Selborne

a nearly inaccessible hamlet.

The main village street, on which stands

our inn, boasts no name, yet it is lovely to look upon. It is lined

with thatched-roofed cottages in raised gardens that blush with roses

and bright-faced flowers. Vines climb over the white-curtained

casements, in which stand pots of gay blooming plants, and each cottage

door is closed by a bar. This is done to keep the little toddlers we

see peeping out curiously from tumbling among the carefully tended

garden-beds. A bird-cage well out of the reach of the family cat hangs

on nearly every cottage wall, with finches chirruping gaily in their

wicker prisons.

The ancient church dominates the entire

village. The square, squat Norman tower is shaded by a huge yew-tree,

reported to be a thousand years old; its dense foliage and

wide-spreading branches almost hide the body of the church. Near the

church is the vicarage. The old house in which Gilbert White was born

has been replaced by a modern dwelling, but the lovely garden where he

took his first steps among the flowers still thrives and flourishes

under the watchful care of the present vicar, Mr. Kaye. The yew-hedge,

planted over two hundred and fifty years ago, is now a superb wall of

green, and beyond its impenetrable foliage lies the churchyard. In a

nook made by an angle in the transept wall is the grave of Gilbert

White. A worn stone, in which are roughly carved the letters "G. W.,"

marks his last resting-place. He was born in 1720; his grandfather was

vicar of Selborne at that time. Here in the vicarage he was at home

until he entered Oriel College at Oxford, and here he returned before

taking up his residence at The Wakes and assuming the duties of curate

at Faringdon. While the colonies in America were fighting the mother

country, and France her royalty, Gilbert White, in a village nearly cut

off from the world by bad roads, was writing of the insect world to his

friends. In 1776, he is more interested in a cat who has mothered a

leveret than in the Declaration of Independence. In 1793, when royal

heads are falling across the Channel, he writes chiefly of sand-martins

and their young.

Since the death of Gilbert White there

have been some additions to his home by later owners, but the new

building has all been done in the spirit of the original dwelling. The

comfortable modern drawing-room and the pleasant dining-room are in

harmony with the old study used by the naturalist, now the favourite

den of the present owner. Out of the drawing-room a passage through a

well-filled conservatory leads to the lawns and beautiful gardens, but

little changed since the days of the naturalist. The trees he planted

are carefully preserved, and the sun-dial on which he noted the passage

of the hours still stands on the lawn.

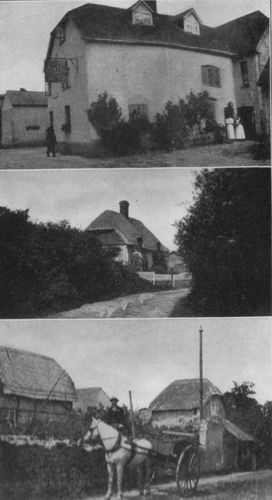

The Queen's Arms – On Gracious Street

– The Entrance to the Village.

Looking over the churchyard stile, on

the side of the Plestor (a playground for the village children), we see

The Wakes on the other side of the sloping space. The long, rambling

brick house, placed close upon the street, is shrouded to the very

gables by trees and shrubs, which hide the windows from inquisitive

eyes.

The early evening hours, in a country

where the twilight lasts until nearly ten o'clock, are the most

delightful times for walking. We climbed the Hanger after tea, with the

comfortable feeling that dinner could wait until we came back. There is

a steep path, called the Zigzag, said to have been cut by Gilbert

White, but we chose to gain the hilltop by a long, sloping ascent

winding up with an easy sweep under the beeches. At the top, from a

bench placed there for the comfort of wayfarers, through a clearing in

the wood, we looked down upon the sunny garden of The Wakes, and its

windows hung with ivy. Behind the house the church lifted its tower,

and still farther on the dusky trees of the Lythe twisted away like a

monster green serpent to the misty hills of the horizon. On the right,

smoke rising above the cottage roofs, buried in foliage, told of the

preparations for the evening meal, while on the left, down the yellow

road which winds along the steep hill toward Alton, came the ploughmen

and their horses.

A sheep-common stretches all over the

top of the Hanger, and a misleading path among the bracken and

scrub-oaks goes to a most interesting little hamlet, Newton Valance.

"Who wants to see a haunted house?"

"Everybody."

I march boldly ahead, with my friends

straggling behind. Fortunately for my reputation, the many lovely views

they get of the valley absorb their attention and save me from utter

disgrace. When I finally hail with glee an avenue of gloomy pine-trees,

I have, unknown to my comrades, lost and found the way not less than

five times.

The haunted house – so

called – is built almost within the Newton Valance

churchyard. The gloomy entrance, the neglected park, the empty

glass-house, the forsaken aviary, and the huge dilapidated stone barns

tell a dreary tale. The falling mansion is only to be described as a

solid Elizabethan manor-house with a Greek villa tacked on to the

front. Any more incongruous mixture of architecture it would be

difficult to imagine. The country folk have invented weird tales on the

strength of some bones found inside one of the plaster statues which

embellish the Greek porch.

"They do say all sorts of things, but we

ain't never seen no ghosts," the caretaker tells us. She lives in the

only habitable part of the decayed mansion, which is the great kitchen,

with a large family of children. Their laughter and games perhaps

frighten ghosts away. The original house was evidently built in

Elizabethan days for lavish hospitality, but that was before the owner

with shabby Greek taste appeared. Inside, in the ancient part, the

rafters are rotting, while in the modern addition the gay

French-mirrored doors are cracked and the walls covered with mould.

A long avenue, grass-grown and disused,

goes straight down the other side of the Hanger, past two fallen

lodges, and then through rusty gates, hanging each by a single hinge,

out on to a pretty, cheerful road, along which Gilbert White lingered

often to contemplate the wonders of his beloved mistress, Dame Nature.

He was curate of the little village of Faringdon, through which this

highway passes before it skirts the borders of Chawton Park.

Jane Austen House, Chawton

The Chawton of to-day is much as it was

in the time of the authoress who there wrote "Pride and Prejudice," as

well as all her later novels. The square brick house in which Jane

Austen lived when her brother became lord of the manor is opposite the

tiny inn, on a picturesque road of thatched cottages hiding behind

verdure-grown garden walls, over which nod masses of tall, yellow

flowers.

We were lucky in coming to Selborne in

July. Then occur the most festive days of the summer, the flower-show,

and the county policeman's dinner.

The flower-show is held in a large tent

pitched on the lawn in the park of The Wakes. The many gardens which

the villagers have carefully tended all through the year then give up

their choicest specimens for this exhibition. The schoolchildren spend

hours gathering wild flowers to compete for the prize given that little

one who shall show the greatest variety arranged with the best taste.

The Wakes, from the Hanger

The love which the English rustic has

for flowers, and the skill shown in growing and arranging them, comes

out fully at a village flower-show. The Invalid and the Matron were

most enthusiastic when they saw the successful efforts of the children

and the outcome of the gardens. They had formed their judgment of

British taste by the dress of the women.

The prizes were plentiful and

substantial. They were distributed by the charming wife of the squire.

The villagers looked pleased and happy, but the only noise and applause

was furnished by the squire's pet bulldog, who accompanied the

announcement of each prize-winner with loud barks and wild leaps of

joy, to the intense disgust of the vicar's poodle, who sat by with the

dignified bearing his station in life required.

There was music and dancing in the park,

while just beyond the gates a shabby caravan from Petersfield, a

near-by town, waited with its swings, carrousel, and shooting-gallery

to swallow up the prize-money.

The squire's hospitality is responsible

for the policeman's dinner. It is his entertainment. The constabulary

is a valuable and imposing institution in rural England. During the

hop-picking season Selborne and the country for miles around is overrun

by rough men and women from the dregs of the London streets, who come

to work in the hop-fields.

That muscular member of the county

police who keeps the peace in Selborne has proved himself such a terror

to the evil-doers among these hordes that the squire, with a desire to

show his appreciation for the protection afforded his village by this

athletic policeman, once a year gives a dinner in his name to all the

members of the constabulary for miles around. For many days before the

great event the innkeeper's wife and daughter are busy all day roasting

joints, baking cakes, and preparing dainties. Our meals are irregular;

the Invalid murmurs; the Matron makes excuses; but we only get fed

after a fashion until the great day arrives.

As early on that morning as is

consistent with British habits (between ten and eleven) the guests

drive into the yard of the inn. They bring their wives and children,

their sisters and mothers. They come in busses, they come in

wagonettes, in dog-carts, and every description of vehicle drawn by

horses. In the coffee-room, in the parlour behind the bar, and in the

tap-room tables are set. We were invited to go down and admire the

flowers and the wealth of good things in which the British palate

delights.

The County Constabulary is a very

important institution, but the annual dinner of the County Constabulary

is a much more important institution. We were greatly disappointed,

being females all, and Americans as well, to find that the invited

guests did not come in uniform. We finally decided that it would never

do to damage the immaculate smartness of the village policeman's

official attire by risking its glory at games on the green. The men

came therefore in those spick and span garments in which every

Englishman manages to array himself on Sunday. The women were as dowdy

as the men were trim, the children were cherubs, like all English

children, and the horses groomed until they shone like satin.

The visitors drove into the yard with

either a flourish of whips or of horns, as the style of vehicle

demanded. The women and children were helped out, and went their

various ways, to visit in the cottages, or to admire the gardens.

Before the men even glanced into that most inviting tap-room, the fat,

sleek horses were taken from the shafts, led away to shelter and

comfort, and the carriage cushions turned over to save them from the

sun. When these necessary duties had been performed according to the

tidy ways of this most tidy people, mild sounds of mirth began to issue

from the tap-room. It would not be consistent for the chosen

representatives of the sternness of the British code to be other than

mild.

The landlady and her daughters were busy

showing the culinary triumphs in the coffee-room to the women visitors.

These gazed and admired, but dared not taste. The feast was not for

them until their lords had eaten their fill. The inn is too small to

accommodate all; the occasion being a policeman's dinner, the policemen

ate first. After the women had looked and approved, the men marched

slowly in to the banquet; we watched them from the window above. A

period of perfect silence told loudly of the merits of the viands, but

after a time the guests waxed merry. When the Squire came in to the

dinner, he was greeted with song: "For He's a Jolly Good Fellow,"

which, nobody venturing to deny, was repeated countless times.

After the meal was over came games at

The Wakes. We had fortunately received an invitation to be present. We

sat on the lawn under the glorious old trees and watched the game of

cricket, which we did not understand in the least; a tug of war pleased

us better, it came quite within our limits of comprehension.

The host of the occasion wandered about

talking with old and young. We were exceedingly interested in the

relations between the classes here displayed. It was a novel sight for

republicans, no equality, no condescension, yet not the slightest sign

of servility.1

The policeman's feast is given before

the stern duties of the late August hop-picking season demand their

entire attention. When that strenuous time is past, Selborne sinks back

into reposeful quiet. There are no market-days to disturb the peace,

nor any unruly visitors. After the morning eruption of children on

their way to school, the village street is given up to an old labourer

with a full sack on his bent back, varied by an occasional carriage

with showy livery, driven rapidly, and bearing ladies on their way to

call upon neighbours probably five miles distant. To vary the scene

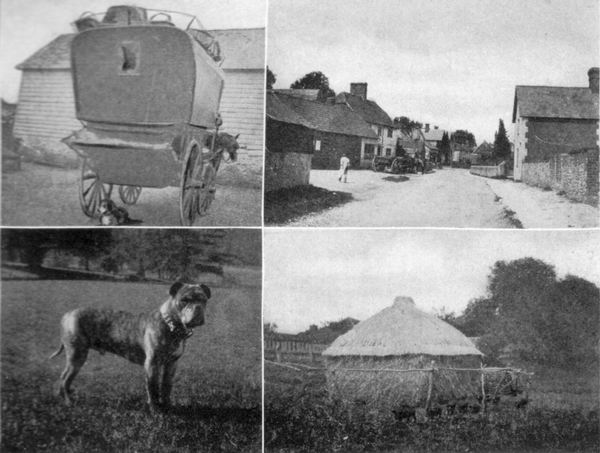

comes the carrier's cart from Alton. It draws up in the inn yard, and,

while the carrier lounges in the tap-room, his panting dog rests in the

shadow under the cart.

"I have been to The Wakes and borrowed a

male escort for our walks," said the Matron one morning. "Where is he?"

demanded Polly. "Outside on the door-step," answered the Matron. "How

rude to leave him there!" Polly exclaimed. "He refused to come in. I

could not force him." "Then he is the rude one. How did you meet him?"

"I was introduced to him yesterday, just after he had finished a

peppery meal of wasps. He is a Scotchman with four legs, a tail twice

as long as his body, and a passion for wasps. When I first saw him he

was chained to his kennel, giving forth the most remarkable growls and

yelps I ever heard. 'Them's Dirky's wasping growls,' said the coachman,

to reassure me. 'You see, ma'am, he 'ave marmalade for 'is tea. The

wasps come around and make 'im angry, but after 'ees eat five or six

'is tea tastes better.'" Dirky's tea consisted of bread and jam, which

naturally attracted the voracious Hampshire wasps in great numbers,

but, after Dirky had executed a war-dance, accompanied by the

death-song, they left him in peace to devour his delectable dish.

We found Dirky a most amiable and

willing guide. He trotted ahead and we followed to the church, where he

exchanged amenities through the fence with the vicar's poodle, while we

visited the Templars' Tombs. As soon as we came out, he resumed the

lead, and away we went through an opening in the churchyard hedge. A

slippery turf path took us down, faster than we intended, to Barton

Cottage, at the entrance to the Lythe. While we strolled across a

quaint foot-bridge, Dirky took to the brook, and came out dripping

before us on the path which skirts the valley under the beeches. The

ancient road to the Priory led this way; we had just seen the church

the Priors founded. The Priory was suppressed as long ago as when

Magdalen College in Oxford was founded. William of Waynflete, Bishop of

Winchester, dispersed the Selborne Priors for their unparalleled

wickedness, and bestowed their lands on his new institution of

learning. No sign now remains of the once rich Priory, its

chapter-house, refectory, or dormitories, except the stones which are

incorporated into the walls and cottages of the neighbourhood. Magdalen

College holds the lands, and has the living of Selborne in its gift.

The Lythe path was a favourite ramble of

Gilbert White. He mentions it constantly in his letters. It leads over

stiles and through underbrush to the Priory Farm, a relic in name only

of the former home of the gay monks who vanished with many other

monasteries less deserving of the fate.

Along a rough bit of road, over low

hills and through corn-fields, on a beaten track so narrow that we are

forced to go in single file, with Dirky wagging solemnly on ahead, we

come again upon the village. From the height we stop to gaze enchanted

at the perfect peace and quiet of the scene. The warlike Hampshire

flies, who have pursued us throughout the entire walk with the tenacity

of their kind, are the only blot on the landscape.

The bicycle is a great blessing to an

English tourist. The popularity of these machines has not waned as it

has in the United States. Motor-cars are plenty, but they are beyond

the reach of travellers like our party; we are glad that we learned to

ride wheels. The roads about Selborne are in fine condition. Through

Wollmer Forest and past Lord Selborne's estate at Blackmoor is a long

stretch with very few hills to mount. We rode in the long twilight

through deep-cut lanes and through moorland purple with heather.

The sun does not give us here at its

setting the brilliant fireworks with which it often favours us at home,

but, when we sit in the smiling garden of the Queen's Arms after

dinner, we are content to see the trees in the Lythe slowly change to

every conceivable shade of green with the fading light. At this hour, a

long line of white geese, who spend their days in the paddock back of

the garden, can be seen marching gravely home, in single file, in

answer to a whistle from the farm where they belong. A dozen or more

tiny black pigs, who are growing up in the same field, do their best to

break up the military goose line with their gambols, to the intense

delight of the innkeeper's tame magpie, who sits on the fence with his

black head popping up among the sweet-pea blossoms and squawks.

We spent a good part of our last day in

Selborne deciding how to proceed on our journey. Winchester lies on our

route to Devonshire, and it is but twelve miles by road from Selborne

to Winchester. We counted shillings, and finally concluded to take the

first stage of our journey by carriage. Our bicycles had been returned

to the man in Alton, from whom we hired them, but, even had we owned

the wheels, the rumour of a mighty hill with three miles of continuous

ascent would have prevented our using them on the road.

Many of our countrywomen would have

disdained the simplicity of our inn, which lacked all the luxuries to

which most Americans are accustomed, but we left it with keen regret,

glancing back until a fall of the road hid village and inn completely

from our sight.

The way to Winchester leads over through

pretty villages clustering along the banks of the river Itchen, which

here, as a tiny stream, gives little promise of the huge mouth it opens

in Southampton.

We stopped for tea at the

uninteresting-looking town of Arlesford. The pilgrims in the Middle

Ages, on their way to Canterbury, halted at old Arlesford. It is now

fast asleep, except on market-days, but there is good hunting

hereabouts, as the inn signs proclaim. "The Hare and Hounds," "The

Horse and Groom," "The Fox" mean sporting patrons. These houses of

entertainment date from stage-coach days. Their picturesque charms are

quite ruined now by the ever-present brewer's advertisement which

invariably disfigures the quaint architecture.

Itchen Abbas, a most delicious stretch

of comfortable homes behind high hedges and smooth lawns and shaded by

great trees, is our last halt before entering Winchester. We

appropriately halt at "The Coach and Horses" to water the horses.

Carriages, with smart liveries, rolling to and from Winchester caused

Polly to declare: "Here live the gentry!" She talks of "gentry" with

the delight every one takes in a word seldom needed. While she is still

turning it over on her tongue, we clatter through a fine carved gateway

at the head of the High Street, and go down to "The George," where to

welcome us the saint and his dragon are painted in glowing colours on

the corner of the house.

The Matron casts a longing glance across

the street at a black swan carved in high relief with a proud motto

underneath and a gold crown upon his head. She thinks that an inn with

such a fine sign must have very superior accommodations, but to The

George we have been taken, so at The George we remain. This hostelry

has existed as an inn for several centuries; now, very much restored

and reconstructed, it has dropped the homelier name of inn for the

grander title of hotel. The old courtyard into which the coaches drove

has become a glass-covered palm-garden, and the coffee-room has its

duplicate in every other cathedral town, yet there hangs about the

house an old-fashioned air of comfort which is never found in the newer

hotels.

The fluent writers of the Penny Guides

give full descriptions of the glories of Winchester Cathedral, and a

guide-book, which costs sixpence, fairly overflows with information. We

did not follow strictly these learned writers' advice. Polly refused to

admire the graceful perpendicular architecture of the nave, and the

Matron could not be torn away from the dream of knights and ladies,

induced by the grandeur of the rude Norman transepts, while the Invalid

lingered entranced before the delicate carvings of the rich mortuary

chapels in the choir.

"If architecture is frozen music, each

one of these is a sonata," she exclaims. One of the most lovely of

these monuments a barbarian called " Pummel " has disfigured with his

hideous name.

There is nothing more wonderful to my

mind, among all the wonders of Winchester Cathedral, than the

beautifully coloured effigies of bishops and prelates, which

fortunately escaped the vandals of the iconoclastic days of the

early Reformation. Cardinal Beaufort, a son of that very turbulent

gentleman, John of Gaunt, lies here carved in marble, clad in

magnificent red robes, looking prosperous and satisfied. He was rich,

powerful, and generous, for it is said he gave four hundred thousand

pounds to improve the condition of the poor prisoners of his time.

The ancient kings of England are more

interesting in Winchester than they are in history. Their remains, here

gathered together in chests as dainty as jewel-caskets, are placed high

above on the choir screen. Their names and the dates of their reigns

were the plague of my school-days. When the wise verger who was guiding

us about mentioned casually that one painted casket on the right

contained, as remains of one of the many Ethels, four skulls and six

thigh bones, and another on the left was filled with assorted biceps

belonging to an Edward, no one was the least surprised. Our child's

history taught us these kings were capable of an unlimited number of

heads and countless minor members.

The patron saint of the cathedral,

unlucky St. Swithin, lies low in the hospital for damaged carvings

behind the high altar.

"Serves him right," observes the

irreverent Polly, whose nerves are affected by the weather.

At the side of the great portal there

hangs on the wall some exquisite grille work. These fragments were

parts of the former gates used to keep the evil-smelling pilgrims out

of the choir. Through open ironwork they could witness the ceremonies,

and yet not bring contagion to the monks. These gates are soon to be

replaced for the sake of their artistic value; evil odours have now

quite departed from this fresh island.

At the entrance to the cathedral, along

with the prohibition which curbs a man's desire to marry his

grandmother, hangs an urgent request that "all worshippers shall leave

their dogs at home, lest their antics disturb the congregation."

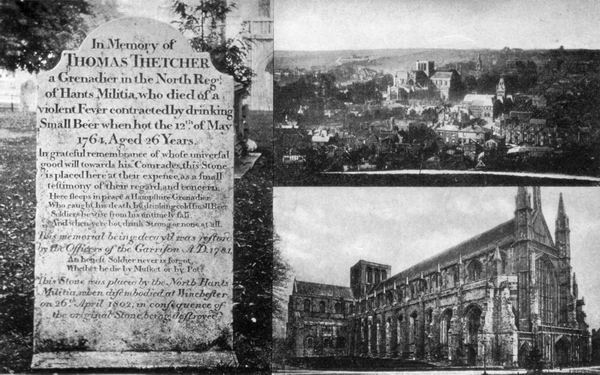

A few steps in front of the grand portal

is the tomb of Private Fletcher, a grenadier whose only claim to

perpetuated memory is that he died from drinking small beer when

overheated. What small beer may be none of this party has ever heard.

It is evidently much more deadly than any other kind. His comrades and

grenadiers of succeeding generations have deplored his fate in a

lengthy inscription on his fine tombstone.

Tombstone of Private Fletcher – General View of

Winchester – Winchester Cathedral.

The turbulence of old times in

Winchester, when the king sent messengers to defy the Church, the Pope

sent cardinals to intimidate the king; when the bishops came here to

quarrel with the nobles, and there was war among all parties, has given

place to a placid old city in which all the excitement is supplied by

the schoolboys of the Winchester College. How far the young gentlemen

of the preparatory school, founded by William of Wykeham, respect their

motto, "Manners maketh man," we had no chance to judge. The long

vacation had deprived Winchester of even that source of gaiety.

Winchester College also has an ideal

conception of the servant question. Above the entrance hangs "The

Trusty Servant," not pretty to look at, but how valuable one may judge

from the description:

"The Padlock shut, no secret he'll

disclose; Patient the Ass, his master's wrath to bear; Swiftness in

errant, the Stag's feet declare; Loaded his Left Hand, apt to labour

saith; The dress, his neatness. Open Hand his faith; Girt with his

sword, his Shield upon his arm, Himself and Master he'll protect from

harm."

________________________________

1 The estate of The Wakes has changed hands

since the above was written. It is now owned by Mr. Andrew Pears, who

will doubtless preserve all the traditions.

|