|

CHAPTER III

Clovelly

HERE being no other passengers, the

coachman smiled respectful approval at us, while he wound his horn

gaily, and off we started over Bideford bridge on our way to Clovelly.

Bideford town lies stretched along the estuary more asleep than awake.

The busy days of Sir Francis Drake have long departed. A few small

coasting-vessels ride by their cables on the great iron rings in the

side of the stone quay, in place of the many galleons just home from

the Spanish Main in these good old days. The quaint inns, where once

browned sailors drank and boasted of their deeds, are still hoary and

picturesque, unchanged outwardly since the departure of the former

rollicking guests. They now depend entirely on a few topers for their

existence.

Bideford is built on a steep incline, so

up we went, too, with vigorous horn-blowing by the guard, until the

last fringe of cheap, ugly villas was left behind, and we were out on

the broad highroad with ten miles of drive before us. Overhead arched a

lovely sky, and to the sea tumbled thick-wooded cliffs. The waters of

the bay were as full of shades and colours as an orchid leaf. The lazy

swells rolled off to the horizon, where Lundy's Island, the former home

of smugglers and outlaws, lay as innocent as a pink sea-shell, changing

its colour and shape to a violet cloud, where the road curves, and

offered us new views every moment.

The whole way to Clovelly is hallowed by

the remembrance of Charles Kingsley and the hero of his great novel,

"Westward Ho!" Indeed the home of Amyas Leigh lay in this direction

from Bideford, and as we drove, so did he stalk along on foot to visit

his friend Will Cary at Clovelly.

The roofs of many country residences

show among the trees. Here and there a bit of the point of a gable, or

a red roof just peeping above the green leaves, Sheep, so big and fat

that we think our eyes deceive us, are feeding in the rich green fields

beyond high, luxuriant hedges. The road dips again and again down

slight hills, and the tinted sea and deep-red cliffs are then shut off,

only to appear again in new colours.

Finally, at a spot among tall, thick

trees, we stop without warning, and the driver announces that our

journey is at an end. There is no house or village; a barn at the top

of the hill, a few seafaring men lounging about a mile-stone, and a

steep woodland path leading apparently nowhere, is all we can see. The

Invalid protests, but the rest of us, more obedient to the driver's

command, climb down from our perch. We are then so much absorbed by the

difficulties of the slipping and sliding descent that, before we have

time to make any comment, by a sudden turn the green balconies, the

funny little bay-windows, and jumble of toy houses buried among flowers

and foliage; announce to us that we are in one of the most noted

villages of England.

It hangs there at our feet, crowded in

between high banks of dark green, zigzagging down the narrow bed of a

former stream to the huge, liquid; opal sea. It has the prosaic name of

Hartland Bay, but "it certainly is like a jewel to-night," declares the

Matron. "The clouds above us are models for poster artists, with their

gay hues and dark, decided outlines."

If, in the picture before us, any

variety was wanting, it was supplied by the red sails of the

fishing-boats slowly rocking to and fro on the glassy water; or by the

sturdy little donkeys who were picking their way from side to side down

the broad cobble-paved steps of the street, bearing our bags and

bundles before us to the door of the New Inn.

When we told our names to the hostess,

the wisdom of sending a telegram several days before our advent was

made manifest. Instead of being packed away in the large and ugly

Annex, we had the original ancient miniature New Inn quite to ourselves.

"I feel as if I had got into my own

dollhouse," said Polly, as she mounted the low step into the

bay-window, and, seating herself there, proceeded to fill its space

entirely.

It is a doll's inn, but so perfectly

proportioned that we had decided that, were it possible to nibble some

of the wonderful Wonderland mushroom on the proper side, we should be

in a palatial dwelling. We have none of Alice's specific on hand, so we

remain big and clumsy, and look with anxiety at the wealth of breakable

objects with which our little sitting-room is encumbered. There are

tables laden down with shepherdesses and cupids, more or less maimed;

on the walls the china plates hang thick, and the mantel-shelf is

littered with vases, great, small, and of middling size, while in every

nook and corner, wherever there is a vacant spot, are flowered

candlesticks.

There are four bedrooms in the little

house, whose closed doors are defended from intruders by huge wooden

latches, quite out of proportion to the possible danger of thieves.

Low, long lattice casements, and a staircase that a tall man could go

down with one step, we have also in our tiny inn. The Invalid's bedroom

looks seaward, and into her window two bold roses peep; they climb up

over the roof of the next house, and nod and bow against the pane, for

in Clovelly the windows of the second story of the house, the next

highest up on the street, get a clean view over the lower chimneys.

While looking at these clustering roses,

we found the new moon gazing at us. The sky, the sea, the cliffs, and

all the beauties of Clovelly were doing their best to enchant our

senses.

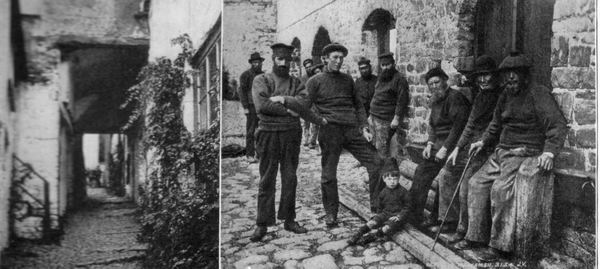

looking down Clovelly Street – Looking up Clovelly

Street

The perpendicular towns so common on

many parts of the Continent, have no more picturesque qualities than

this little hamlet. There are here the same unawaited flights of steps,

unexpected back courts, blind alleys, and mysterious passages under

arches and through houses; but there are here none of the malodorous

horrors and dirt of the Continental villages. Clovelly may have had in

Charles Kingsley's day an ancient and fishlike odour, for he mentions

the smells in one of his letters to his wife, but to-day Clovelly is

swept and garnished in every nook and corner, and the back gardens

blossom and overflow with every kind of flower, painted gaudier by the

soft sea air. The falling, twisting street is a riot of bloom from top

to bottom. Tall fuchsias and great purple clematis fight with the roses

for mastery to the very chimney-tops. The window-ledge boxes fling over

trailing vines, and are gay with geranium and petunia, while pots of

flowering plants adorn each one of the queer little porches, and the

brilliant nasturtiums crowd each other to stare over the walls of the

tiny gardens. Every house is small in Clovelly but the Annex to the New

Inn, and that would not be called large in any other town. Although it

has been lately built, the vines are doing their best to hide whatever

there is ugly about it. All the other cottages well suit the little

white wedge made by the village in the dark hillside. Down by the

water's edge is a small pier, winding itself like a curved arm about

the gaily painted fishing-boats which come to be, sheltered there at

night. There is a diminutive lighthouse at the point of this pier, and

the sea-wall, raised along one side of it, is draped with the rich

brown seaweed, an ornament furnished by nature that blends with the

dark red nets of the fishermen.

The pier follows a natural formation of

rock, which is probably the reason for the existence of a village in

this strange precipitous glen. It is the very best place for lounging

away the long, pleasant twilight; for gazing out around the tall

neighbouring headlands on to the waters of Bristol Channel, and

watching the lights come out slowly in the village hanging above.

Along the pebbly beach are a few houses

looking like escaped Italian villas, their green balconies hanging over

the water's edge.

There is down here a stout ruin of an

early Roman tower, and the Red Lion Inn.

A part of this sober old hostelry was

the birthplace of the sailor, Salvation Yeo, given immortal fame in the

novel of "Westward Ho!" and always the home of his mother, whom

Kingsley makes describe her wandering seaman of a son as:

"A tall man, and black, and sweareth

awful in his talk, the Lord forgive him!"

Here along the side of the Red Lion the

sturdy Clovelly sailormen lounge after their work is done, and it is

probably on one of these benches that Charles Kingsley spent so many

hours of his early youth, listening to yarns and learning sea-lore.

Never was a better spot on earth devised in which to rear a poet and

novelist! All the pleasure he enjoyed here during the long and lovely

Clovelly twilights, Charles Kingsley has given back to the world in his

writings.

There is another lookout above the

beach, reached by crooked stairs from the harbour. Here more of the

sailors gossip the hours away, and here the Invalid and the Matron, the

first evening of our arrival, secured the confidences of the most

friendly among them. The acquaintance began with an ancient mariner,

who persisted in speaking of himself as a foreigner, although he had

lived fifty years in Clovelly and was married to a Clovelly woman. He

was Irish by birth, and it amused our American fancy very much to have

him so persistent in claiming to be foreign. The Matron returned from

this first evening's chat with a stirring tale about the first, last,

and only horses ever seen on Clovelly Street. They appeared in the

ancient Irish mariner's young days. An ignorant and reckless post-boy

attempted to drive a bridal couple to the door of the New Inn, with

such disastrous results that the whole male population of the village

was called upon to save the horses from destruction and to keep the

chaise from rolling down into the sea. This they did by clinging to the

wheels, and turning the horses sidewise on the broad steps of the

street, at the peril of their lives. Fortunately the incident happened

late in the afternoon, when the men had come back from the boats. Our

Irishman was among the rescuing crew.

The landlord of Clovelly is Mr. Hamlin,

who lives in Clovelly Court, close to the top of the village. The

estate has descended to him through the marriage of one of his

ancestors with the Cary family, which included among its members the

Will Cary of Kingsley's novel. Of Sir John Cary, founder of the family

and a judge in the time of Henry VI., a gossipy chronicle says: "He was

placed in a high and spacious orb, where he scattered about the rays of

justice with great splendour."

This extraordinary power, however, did

not prevent the good judge from being exiled during those troublous

times. His confiscated estates were later returned to a son. At

Clovelly Court lived Will Cary. Here within the park gates still stands

the church where Charles Kingsley's father was vicar. In Clovelly park

rises a wonderful high cliff, mounting three hundred feet above the

pebbly beach and bearing the attractive name of Gallantry Bower. From

among the park's trees we looked out upon the roofs of the village,

that seemingly push one another down-hill like naughty children; then

out beyond the jutting Hartland point we saw a dim line which they told

us was the coast of Wales, and across the tops of the village houses

there came into view the deep green wood that rises high on the

opposite hillside. Along this way runs the Hobby drive, a fine, winding

road built by the Hamlins, and for which every visitor to Clovelly owes

them hearty thanks. In the whole world there is no road affording more

truly lovely views of land or sea.

The Matron says that she strongly

suspects the artistic sails of Devon boats (they are of the same red

colour as the Devon soil of the cliffs) originated in the times when

many little casks of good French brandy rolled ashore under the shelter

of Gallantry Bower, and found there proper gallants to receive the

cargo. The sentimental Invalid is very unwilling to believe that this

charming spot was ever used for other than romantic purposes, but

unfortunately, both history and tradition whisper that all the riches

of this coast were not caught with the herring.

The glory of the New Inn Annex is the

dining-room; here the guest not only feasts upon fresh herring, sweet

and tender, but his eyes are edified with much blue china and more

hammered brass. I disdain to repeat Polly's insulting remarks about

their artistic merits or her doubts of their antiquity. Our delighted

eyes behold overhead the entwined flags of England and America frescoed

on the ceiling with striking truth to nature, while under their

gorgeous folds sit the Lion and the Eagle, smiling broadly down on the

guests. For those diners who choose to crane their necks between the

courses, there is a poem painted on the ceiling with as many stanzas as

the old-time ballad; I venture to quote only the beginning and the end

of this inspired lay:

|

I.

"Let parents be

parental,

Think of children

night and day,

And the children be

respectful,

To their parents far

away.

IX.

Our foes we need not

fear them,

If hand in hand we go,

We want no wars with

any man

As onward we do so.

X.

But do our foes assail

us,

We will do our best to

gain,

With our children

standing by us

Britannia rules the

main."

|

Mine host of the New Inn, who beguiles

his winter hours by dallying with the Muses, is responsible for this

poetry.

In addition to its richly hung, walls

and decorated ceiling, the dining-room has still another attraction in

the person of the chief waitress, a young woman very efficient in her

calling, blessed with a sweet voice, attentive, willing, and amiable.

Her fame has spread far and near as the

Beauty of Clovelly. A mass of very blond hair, in strong contrast with

her black eyebrows and eyelashes, appears to be the chief reason for

which this title has been bestowed. Her features are by no means

beautiful, nor is her complexion faultless. Polly says that at least

her peculiar charms are useful as promoting conversation, for, after

she has been seen, every visitor spends the leisure hours discussing

how much of her hair is real, and whether its colour is artificial. One

of the numerous old village gossips, whom the Matron has interviewed,

says that the girl always had the same mass of wonderful hair even when

she was a small child. Peroxide cannot be a convenient beautifier here

in Clovelly, where the entire village supply of drugs would not fill a

market-basket. The Beauty is a niece of the landlady, and does not seem

at all disturbed, or even spoilt, by her peculiar celebrity, which is

so wide that the summer trippers gather in crowds about the inn to

stare at her.

Against these same trippers the ire of

the village gossips is fierce and fiery. From the coast towns they come

by the boat-load to see the wedge-like village, and try to see it so

thoroughly that not only do these strangers tramp into the back gardens

and peer into the windows while the good cottagers are eating, but one

old lady told the Invalid that she had once caught two busybodies just

as they were about to look into her cooking-pots on the kitchen stove.

We were not in Clovelly at the time of any of these invasions, but the

numerous tea-room signs on many small houses bear testimony to how much

refreshment must be sold here on such occasions.

Single blessedness is not the fashion in

Clovelly. On the lookout bench at evening the village bachelor becomes

the butt of all his comrades' chaff. At the time of our visit there was

but one of these despised single creatures in Clovelly. This we

inferred from the jokes thrown headlong at one man, who held his own

boldly for a time, until at last, overcome by twitting sarcasms about

his wealth and beauty, he fled ignominiously to his solitary fireside.

We were inclined to agree with the ancient mariner, who confidentially

whispered to the Matron:

"That man'll be married inside month."

Children are the only human beings who

dare to run down Clovelly streets. They clatter along with so much

noise against the cobble that the Matron insists that their English

shoes are wooden: They begin to troop up and down before six o'clock,

and rattle up and down until the school-bell calls the flock to

lessons. The Matron is very fussy about being disturbed early in the

morning. That others have shared her views, we find from the visitors'

book, where a poetic genius has complained:

|

"Although in Devon

'tis almost heaven,

Down Clovelly streets

is the sound of feet

Not of angels, and not

bare."

|

We had wandered up and down the steep

streets in and out through every conceivable quaint passage, talked to

all the friendly villagers, and admired the adorable flowers, when at

last we gathered on the second evening in our sitting-room, among the

broken-nosed shepherdesses and the cupids with cracked hearts, to

decide on our future plans. We had explored the neighbouring country to

discover the old Roman road, gazed upon the ancient British earthworks,

and revelled in the walk along the Hobby drive. Nothing was left undone

which a proper tourist should do in this unique spot, except, perhaps,

a sail to Lundy's Island. That is a perilous voyage for seasick women,

and we willingly persuaded ourselves that Lundy's Island looked better

from a distance. Had there been a drag going between Clovelly and

Ilfracombe, the charm of the enchanting scenery would have decided us

at once to take that route, but, as it sometimes happens, we were not

fortunate enough to find a party going, and the expense of hiring such

a conveyance was too great for our purses.

A Heart of Oak – Clovelly Foliage

The way to Derbyshire is a longer

journey than we cared to take without a break, therefore, after much

discussion, Evesham was decided as a resting-place. That town lies in

the land where the peaceful river Avon waters useful market-gardens,

and orchards of plum-trees thrive under the lee of that pastoral range

called the Cotswold Hills. A welcome telegram had announced the

recovery of jumbo, and the bag's safe arrival in the cloak-room at

Bideford station. We promptly hurried off another wire (Polly feels so

English when she says "wire") to Evesham to announce our coming to the

landlady of a sunny old farmhouse that looks down over a rose-garden

upon the Avon valley and the town below.

We had decided not to try a real inn

this time, but make an inn for ourselves. The Crown, the chief hotel in

Evesham, is huddled down in the centre of the town, while at Clerk's

Hill House pet garden thrushes would be bursting their little throats

with song to give us a concert at dinner-time. As we bowled along on

our return to Bideford, the accomplished coachman played for us merry

and appropriate tunes. He drove his four horses easily with one hand,

while with the horn he held in the other he wound out a continual

strain of melody. The sea and cliffs along the road had lost the soft

pastel shades we found there on the first late afternoon drive. They

were now bold blue, red, and vivid green in the sharp morning light.

During the half-hour wait for the train,

while the Matron clasped jumbo to her side, and we had each taken a

peep to see if all our valuables were still safe in his embrace, we

looked into the room at the Royal Hotel where Charles Kingsley wrote

the greater portion of "Westward Ho!" The hotel is beside the station,

and was the house described by Kingsley as that of Rose Saltern's

father. In the drawing-room, where the author wrote part, if not all,

of his noted novel, remains a fine Elizabethan stucco ceiling. It is

decorated with garlands, birds, fruits, and flowers, coloured by

artists who were brought from Italy by the merchant prince who lived in

this house during the time of Sir Francis Drake.

|