|

CHAPTER X

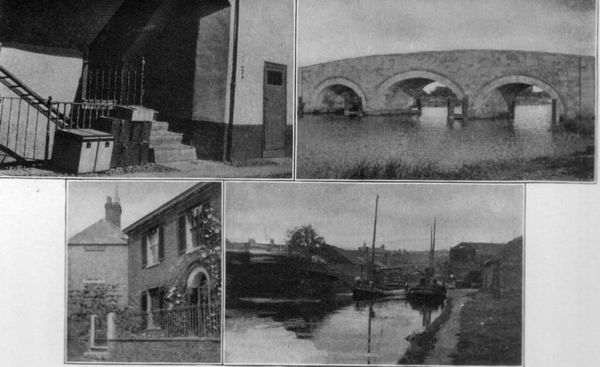

ANGEL INN

Acle Bridge

"WITHOUT a sail on the Broads, I refuse

to leave Norfolk," declared the Matron, as we sat at dinner the night

of our return from Thetford. " It would be rather hard to answer the

questions our numerous friends will ask when they hear we have been in

Norfolk."

"I know lots of people at home who think

there is nothing to see in Norfolk but Sandringham and the Broads,"

continued the Invalid.

"And are not quite sure about

Sandringham, either," finished Polly. " I don't see how we are going to

manage it," said Polly.

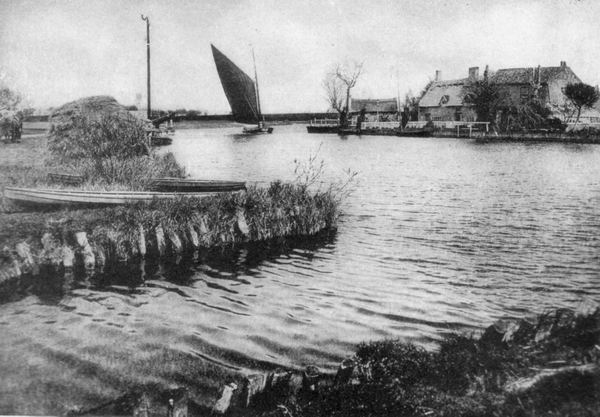

On the Norfolk Broads.

"Go ask the hotel manager, that is the

wisest way, and we will decide ourselves when we hear what he tells

you."

So Polly left us to go into the pretty

Jacobean office, which looks for all the world like a monstrous piece

of oak furniture, and we went on to warm ourselves before the great

thirteenth-century fireplace in the reading-room. What a comfortable,

great room it was! with writing-tables and tables covered with current

literature. Our good luck inspired a gentleman sitting next us to talk

to his wife of a cruise they were preparing to take on the Broads. He

had been that day to engage a large wherry at Thorpe just beyond the

railroad station, and the couple were preparing to live on the boat for

two weeks. From his conversation we inferred that he had evidently

rented a large boat capable of accommodating five or six people, for

which he was to pay a pound a day. A man and a lad constituted the

crew. How we wished we could exchange our coming ocean voyage and the

big rocking steamer for such a quiet cruise and such a roomy wherry!

The gentleman went off to complete his plans. He was not well out of

the room, however, before the Invalid was deep in conversation with his

lady, and asking questions in her most enchanting manner. Who would not

tell the Invalid all she wants to know when she cocks her pretty head

on one side and looks so deeply interested? She entices knowledge from

every one she meets.

Polly returned while the Invalid was

imbibing knowledge, and our scheme for the morrow was satisfactorily

arranged before the questioner rejoined us, bursting with information.

"They will take only a few tinned

delicacies," she began, but never finished; we were too full of our own

projects to listen to what others intended doing.

"We are in great luck," began Polly.

"The manager referred me to the lady-manager, who, when she heard what

we wanted, at once said that there happened to be two young men

stopping in the hotel who had a large wherry at Wroxham Bridge which

they wanted sailed down to Yarmouth. She had heard them talking about

it to-day. They would let us hire it, she was sure, because they did

not wish to rejoin the boat until sometime at the end of the week. If

the wind is right, she says we can make the necessary twenty-six miles

in a day. Even if there is not a spanking breeze, it will be possible

to see one or two of the Broads, and come back by rail from Salhouse or

Acle. The manageress then went off to fetch one of the young men, and

came back instead with their decision. We can have the boat to-morrow

morning if we are each willing to pay them three dollars apiece for the

day's pleasure; that sum will include luncheon, which we can take from

here."

"Oh, why not stop at a riverside inn,"

exclaimed the Matron.

"We won't have much time for stopping

unless the wind blows a gale or doesn't blow at all," answered Polly.

So we decided to take the wherry and see

what we could.

We woke early on the eventful day to

find the weather all we desired. Our plan of action included a very

early breakfast and an early train to Wroxham Bridge, where we were to

join "our ship," as Polly insisted upon calling it.

"Come early and avoid confusion," was

the somewhat banal quotation the Invalid made when we stepped into the

railroad carriage.

For the first time in our travelling

experience, Thorpe station did not resemble a hive of crazed bees. The

English are not commonly stirring very early in the morning, and there

were but a few passengers in the train besides ourselves. Wroxham

Bridge lies eight miles from Norwich, and we were soon on board the

wherry, which we found waiting at the landing. "There was a good

breeze!" the skipper informed us. "If it kept up, we would be able to

make our voyage to Yarmouth."

As the skipper proceeded to haul up the

sail, the Matron exclaimed with delight: "It is black!"

"And we have a pink and purple boat,"

chimed in Polly.

"Only green and red," contradicted the

Invalid.

At Wroxham Bridge countless boats of all

sizes are gathered together. This is the halting-place for most of

those who sail the Broads. We had twenty-six miles before us,

– the distance by water to Yarmouth, –

and we flew along with our black sail reefed. We skimmed between the

flower-decked banks of the narrow stream into a spacious sheet of green

rippling water, called Wroxham Broad.

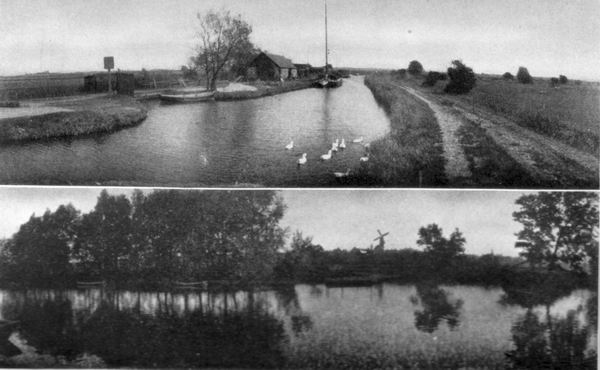

On the Broads, Near Acle – A View Near Norwich.

Polly asked the skipper why these little

lakes are called Broads.

"Because the stream is broad here," was

the lucid answer.

Wroxham stretched out before us like a

long lake. The reeds grew thick on the shore, and beyond them were

clumps of low trees and broad meadows of soft-coloured grass, green

fruitful park-lands, and glimpses of cattle in the shade. From Wroxham

Broad our boat wound down a small stream, past a quaint village built

along the water's edge on low swampy ground, showing colours of purple,

green, yellow, and red in the meadow-grass. Away we went past a

delightful, quaint inn at Horning Ferry. Here the Matron clamoured to

stop and eat lunch under the sturdy willow-trees, but time was precious

and the wind in our favour, and the skipper would not allow us to stop

at Ranworth if we lingered at Horning Ferry. The Invalid had registered

a vow to see in that hamlet an old church which boasts a celebrated

rood screen. We therefore sailed along, discussing willows and luncheon

at the same time, and we were in Ranworth Broad, flying before the

wind, before we had ceased regretting the Horning inn. The hills

suddenly rose on one side of the water. Thick trees crowned their

sides, but we got peeps at neat cottages and a church or two. Before we

entered Ranworth Broad, the skipper told us of a model village,

Woodbastwick, where the cottages are said to be like rose bowers, the

village green is an ideal spot, and the church is full of wonderful

brasses.

"Why can't we see everything?" sighed

the Invalid.

"It is sometimes more satisfactory to

hear descriptions than to see places," replied the suspicious Polly.

We pushed in among the rushes about the

landing-place, where lay bundles of reeds stacked up for the thatchers,

and the only building visible was a hoary old cottage, deserted save by

a cat and her kittens who were having great games together in the small

window.

A tidy old inn, the Malster, was

discovered at a turn in the road, and Polly and I went in to see if the

landlady could furnish us with some cream for our tea, while the Matron

and the Invalid took their way onward up a short hilly road to the

church.

Ranworth is a hamlet. It has not even a

"village store"; the cottages are tucked away in little crannies of the

uneven ground; there is no railway within several miles; a cheerful

parsonage and a comfortable manor-house are the only dwellings except a

few small cottages. When Polly and I left the Malster, and climbed the

road to the church, we found the Matron embracing two very beautiful

white Borzoi hounds, while a cheeky little black Scotch terrier looked

on and barked in disgust. The Invalid was not visible, and, as soon as

the Matron could get her head away from the dogs, she told us that the

vicar had met them and he was now inside the church, showing the

Invalid the noted painted screen she had so wished to see. The Matron

frankly "preferred playing with his fine dogs to seeing any ancient

screen, no matter how lovely."

"Remember we can only have ten minutes

here," said methodical Polly, and we left our companion romping with

the graceful hounds. My heart was divided between the screen and the

dogs, so I took the screen first. Those who like antiquities are

prepared to rave about everything, whether it be really worth their

enthusiasm or not, but even the greatest of Philistines, and I am of

their number, could see the beauty of this old church and its painted

reredos, I rushed out as soon as I had looked at it, and forced the

Matron to come back with me, if only to admire for a moment the

elaborate flower-work and the splendid colours in the dresses of the

saints. There proved to be other interesting things in Ranworth Church.

A fine old font and a curious lectern are, with its screen, among its

prized possessions. Our skipper told us that it is the church best

worth visiting on the Broads.

"I must return some day and see your

dogs," cried the Matron, when she hears they have a kennel full of

puppies.

"And I want really to live a summer in

this country, through which we only have flown to-day," added the

Invalid.

The wind still held good, so we sailed

down the river past St. Benet's Abbey. A queer ruin this; it looks like

a giant hop-kiln. The remains to be seen from the water of this once

very rich and powerful monastery are meagre, though at nearer range

some of its tall arched doorways appear, and the hues on the marshy

meadows about the ruins make a poetic picture of the few stone walls

still left standing.

We had not the time to enter South

Walsham Broad, about which there is great excitement in the

neighbourhood, for fear the squire will fulfil his threat and close its

waters to the public.

"South Walsham," said our skipper, "is a

charming village, and the Broad small but lovely." We had no time to

linger, but flew with well-filled sail past the windmill at its mouth,

where another small river joins the Bure. Our course was straight away

for Acle Bridge. The stream runs rapidly between banks, protected from

the encroachment of the water by bulkheads. The meadows, on which great

herds of cattle and horses were feeding, were bright with the scarlet

flame of the poppies, and soon the three-arched Acle Bridge was before

us, and many windmills twirled their white arms over the flat land.

Down went our mast, as we slid under the middle arch of the bridge, and

we tied up for tea at the Angel.

"The skipper says we need not hurry; we

have but twelve miles still before us. With a good wind we should be in

Yarmouth before eight, even if we while away an hour before leaving

here. Let us order tea, and then go to the village," suggested our

Matron.

Acle proved to be half a mile from the

inn. The village consisted of a group of houses without visible

gardens, built on three sides of a village green minus any green thing,

excepting one great tree. But we shall always have tender remembrance

of it for the sake of the larks who sang us enchanting trills and

roulades as we took our way back to the Angel. The sun was getting low,

the evening light was golden, and the songsters were rising for their

last flight, their voices loud and clear when their tiny forms had

become mere specks in the glowing sky. As we started off again down the

river, the air was full of their music. This part of the Bure is a land

for painters; a great, flat sweep of country, with here and there a

group of trees about a red farmhouse, or a beckoning windmill. The

sails of many boats, black, white, or coloured by the weather,

apparently skim over the distant meadow; now and again a little

red-brick village nestles down near to the water's edge, and every high

point of land is crowned by a noble square flint church tower. Even the

moon was kind to us, and came up, peeping out among pink clouds, to

make our way more beautiful.

"You should take a month to see the

Broads and a year to see Norfolk," was the skipper's oft-repeated

advice. We agreed humbly. We had passed villages we longed to explore,

and Broads of which we could not even get a glimpse. The flint

churches, with their thatched roofs, all out of proportion to the size

of the congregations who support them, are sprinkled thick over the

landscape, and the skipper told the Invalid such tales of the treasures

in brass and carving they contain that she heaved mighty sighs of

longing. We made a record sail; we skimmed down Wroxham Broad and

peeped into Ranworth, but we passed by five other little lakes. We

heard tales of three others into which our large boat could not sail,

but which are well worth visiting. A summer land flitted past our eyes,

and we hated to leave it. Along the banks and in small boats out in the

stream we saw patient anglers, and one queer little covered boat,

moored in the reeds, was pointed out as the abode of a professional

eel-catcher. It was a diminutive house-boat of exceedingly rude

description. Polly and the Invalid plied the skipper with practical

questions.

An Inn Doorway – Acle Bridge – In

Acle Village – A Boat Dyke.

For a party of four or five, the expense

of two weeks on the Broads would not exceed three dollars apiece per

day, taken in the most extravagant fashion. For the artist there is

sketching, for the sportsman fishing and sporting, and for every one a

lazy, happy life surrounded by unwonted beauty of scene.

"To be sure, there be the Rogers

sometimes," said the skipper, who is listening attentively to our

ravings.

"The Rogers! Who are they?" asked Polly,

looking around, as if she expected to see an army of tramps or worse

bearing down upon us from the shore.

"The Rogers? Oh. they are a sort of

squall," he explained, Oh. they Polly was so relieved that she forgot

to ask why they bear that name, and left the skipper to continue his

tales of the good skating and ice-boating to be had upon the Bure and

the Broads in fine winter weather.

As we neared Yarmouth, the changing sky

and the moonlight made lovely the banks which in brighter light might

look dull and squalid, and, when the dark outlines of the town houses

appeared on the horizon, we had a scene to thrown an artist into a

state of ecstasy. From our boat at the stone quay, we had but a short

walk, amid the old buildings, to the station, where a train returning

to Norwich was just about to depart.

The day had been so crowded with

experience that it seemed a week long.

"We at least know where to go when, next

year, we come back to Norfolk," philosophizes Polly.

"I shall sail the Broads," said the

Invalid, gazing back at the great wherry with a sigh. Early next

morning we left our comfortable lodgings at the Maid's Head. Again we

saw Wymondham and Thetford in the distance as the train flew past, and,

with a glimpse of Ely and Cambridge on our way, we pulled up at last in

London again at St. Pancras. We had left many things undone. We had not

seen half Norfolk, but we had discovered that it is a county full of

diversified charm, and with greater variety than any part of England

into which our tour had led us. The Maid's Head was not cheap, perhaps,

but it was good, for all the inns which glory in the modern title of

hotel cost at the very least three or four dollars a day. Norfolk is

rich in charming little wayside inns, picturesque and tidy, but, as we

found elsewhere, they had no beds to offer the traveller; plenty to

drink, but little to eat. The majority of the smaller and older inns

have fallen into the hands of the brewers, alas! who care more for the

sale of their beer than for the preservation of the picturesque and

ancient hospitality.

Our tour was over with our farewell to

Norfolk and our sail on the Broads; and the whole party have fallen so

deeply in love with the little country full of green fields and singing

birds, bright flowers, pleasant hostelries, and civil, simple people,

that they look forward with longing to future expeditions in other

counties of Merrie England.

|