|

A SHORT HISTORY AND

DESCRIPTION OF THE KELMSCOTT PRESS.

The foregoing

article was written at the request of a London bookseller for

an American client who was about to read a paper on the Kelmscott

Press. As the

Press is now closing, and its seven years' existence will soon be a

matter of

history, it seems fitting to set down some other facts concerning it

while they

can still be verified; the more so as statements founded on imperfect

information have appeared from time to time in newspapers and reviews. As early as 1866

an edition of The Earthly Paradise was projected, which

was to have been a folio in double columns, profusely illustrated by

Sir Edward

Burne-Jones, and typographically superior to the books of that Art and Craft of

Printing,

by William Morris 3 time. The

designs for the stories of Cupid and Psyche, Pygmalion and the

Image, The Ring given to Venus, and the Hill of Venus, were finished,

and

forty-four of those for Cupid and Psyche were engraved on wood in line,

somewhat in the manner of the early German masters. About thirty-five

of the

blocks were executed by William Morris himself, and the remainder by

George Y.

Wardle, G. F. Campfield, C. J. Faulkner, and Miss Elizabeth Burden.

Specimen

pages were set up in Caslon type, and in the Chiswick Press type

afterwards

used in The House of the Wolfings, but for various reasons the project

went no

further. Four or five years later there was a plan for an illustrated

edition

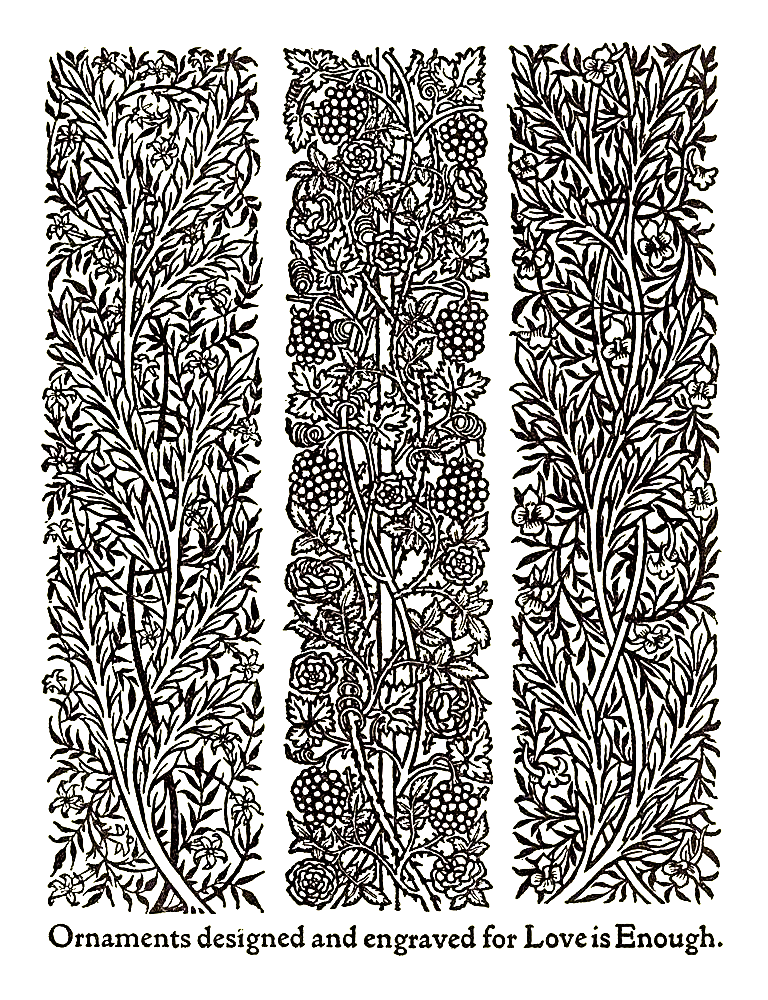

of Love is Enough, for which two initial L's and seven side ornaments

were

drawn and engraved by William Morris. Another marginal ornament was

engraved by

him from a design by Sir E. Burne-Jones, who also drew a picture for

the

frontispiece, which has now been engraved by W. H. Hooper for the final

page of

the Kelmscott Press edition of the work. These side ornaments, three of

which

appear on the opposite page, are more delicate than any that were

designed for

the Kelmscott Press, but they show that when the Press was started the

idea of

reviving some of the decorative features of the earliest printed books

had been

long in its founder's mind. At this same period, in the early

seventies, he was

much absorbed in the study of ancient manuscripts, and in writing out

and

illuminating various books, including a Horace and an Omar Khayyám,

which may

have led his thoughts away from printing. In any case, the plan of an

illustrated Love is Enough, like that of the folio Earthly Paradise,

was abandoned. Although the

books written by William Morris continued to be reasonably

printed, it was not until about 1888 that he again paid much attention

to

typography. He was then, and for the rest of his life, when not away

from Hammersmith,

in daily communication with his friend and neighbour Emery Walker,

whose views

on the subject coincided with his own, and who had besides a practical

knowledge of the technique of printing. These views were first

expressed in an

article by Mr. Walker in the catalogue of the exhibition of the Arts

and Crafts

Exhibition Society, held at the New Gallery in the autumn of 1888. As a

result

of many conversations, The House of the Wolfings was printed at the

Chiswick

Press at this time, with a special type modelled on an old Basel fount,

unleaded, and with due regard to proportion in the margins. The

title-page was

also carefully arranged. In the following year The Roots of the

Mountains was

printed with the same type (except the lower case e), but with a

differently

proportioned page, and with shoulder-notes instead of head-lines. This

book was

published in November, 1889, and its author declared it to be the

best-looking

book issued since the seventeenth century. Instead of large paper

copies, which

had been found unsatisfactory in the case of The House of the Wolfings,

two

hundred and fifty copies were printed on Whatman paper of about the

same size as

the paper of the ordinary copies. A small stock of this paper remained

over,

and in order to dispose of it seventy-five copies of the translation of

the

Gunnlaug Saga, which first appeared in the Fortnightly Review of

January, 1869,

and afterwards in Three Northern Love Stories, were printed at the

Chiswick

Press. The type used was a black-letter copied from one of Caxton's

founts, and

the initials were left blank to be rubricated by hand. Three copies

were

printed on vellum. This little book was not however finished until

November,

1890.

Meanwhile

William Morris had resolved to design a type of his own.

Immediately after The Roots of the Mountains appeared, he set to work

upon it,

and in December, 1889, he asked Mr. Walker to go into partnership with

him as a

printer. This offer was declined by Mr. Walker; but, though not

concerned with

the financial side of the enterprise, he was virtually a partner in the

Kelmscott Press from its first beginnings to its end, and no important

step was

taken without his advice and approval. Indeed, the original intention

was to have

the books set up in Hammersmith and printed at his office in Clifford's

Inn. It

was at this time that William Morris began to collect the mediæval

books of

which he formed so fine a library in the next six years. He had made a

small

collection of such books years before, but had parted with most of

them, to his

great regret. He now bought with the definite purpose of studying the

type and

methods of the early printers. Among the first books so acquired was a

copy of

Leonard of Arezzo's History of Florence, printed at Venice by Jacobus

Rubeus in

1476, in a Roman type very similar to that of Nicholas Jenson. Parts of

this

book and of Jenson's Pliny of 1476 were enlarged by photography in

order to

bring out more clearly the characteristics of the various letters; and

having

mastered both their virtues and defects, William Morris proceeded to

design the Art and Craft of

Printing, by William Morris 4 fount

of type

which, in the list of December, 1892,

he named the Golden type, from The Golden Legend, which was to have

been the

first book printed with it. This fount consists of eighty-one designs,

including stops, figures, and tied letters. The lower case alphabet was

finished in a few months. The first letter having been cut in Great

Primer size

by Mr. Prince, was thought too large, and 'English' was the size

resolved upon.

By the middle of August, 1890, eleven punches had been cut. At the end

of the

year the fount was all but complete. On Jan. 12th,

1891, a cottage, No. 16, Upper Mall, was taken. Mr.

William Bowden, a retired master-printer, had already been engaged to

act as

compositor and pressman. Enough type was then cast for a trial page,

which was

set up and printed on Saturday, Jan. 31st, on a sample of the paper

that was

being made for the Press by J. Batchelor and Son. About a fortnight

later ten

reams of paper were delivered. On Feb. 18th a good supply of type

followed. Mr.

W. H. Bowden, who subsequently became overseer, then joined his father

as compositor,

and the first chapters of The Glittering Plain were set up. The first

sheet

appears to have been printed on March 2nd, when the staff was increased

to

three by the addition of a pressman named Giles, who left as soon as

the book

was finished. A friend who saw William Morris on the day after the

printing of

the page above mentioned recalls his elation at the success of his new

type.

The first volume of the Saga Library, a creditable piece of printing,

was

brought out and put beside this trial page, which much more than held

its own.

The poet then declared his intention to set to work immediately on a

black-letter fount; illness, however, intervened and it was not begun

until

June. The lower case alphabet was finished by the beginning of August,

with the

exception of the tied letters, the designs for which, with those for

the

capitals, were sent to Mr. Prince on September 11th. Early in November

enough

type was cast for two trial pages, the one consisting of twenty-six

lines of

Chaucer's Franklin's Tale and the other of sixteen lines of Sigurd the

Volsung.

In each of these a capital I is used that was immediately discarded. On

the

last day of 1891 the full stock of Troy type was despatched from the

foundry.

Its first appearance was in a paragraph, announcing the book from which

it took

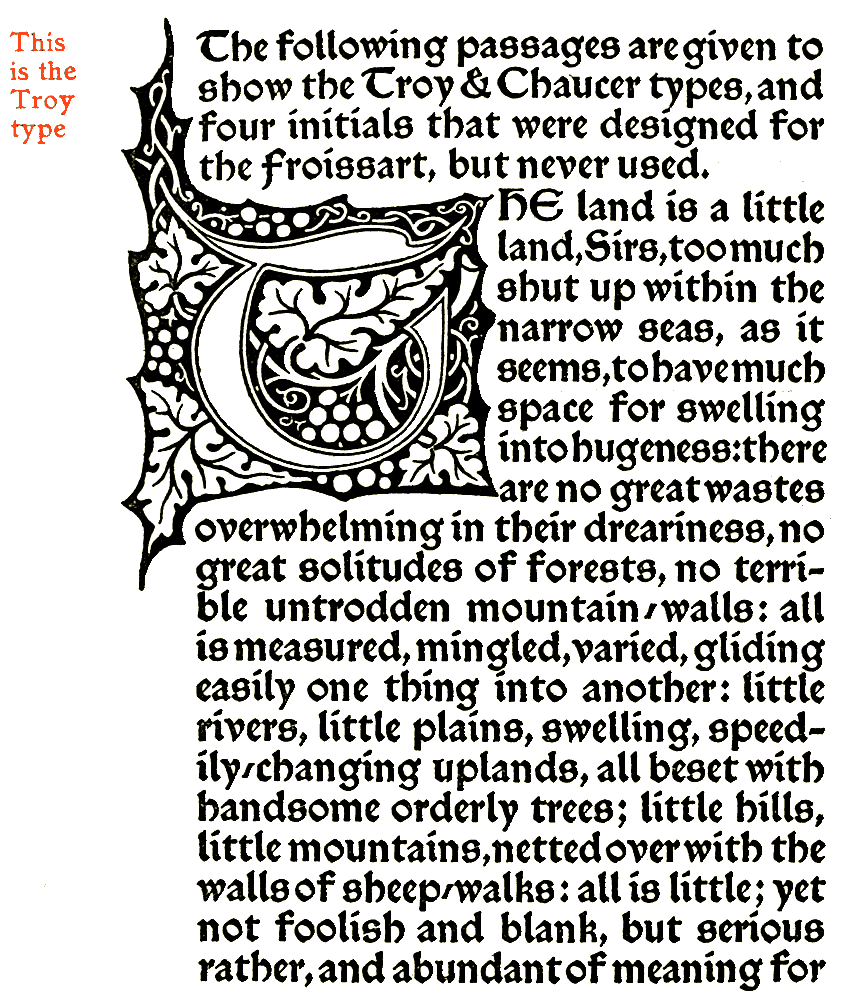

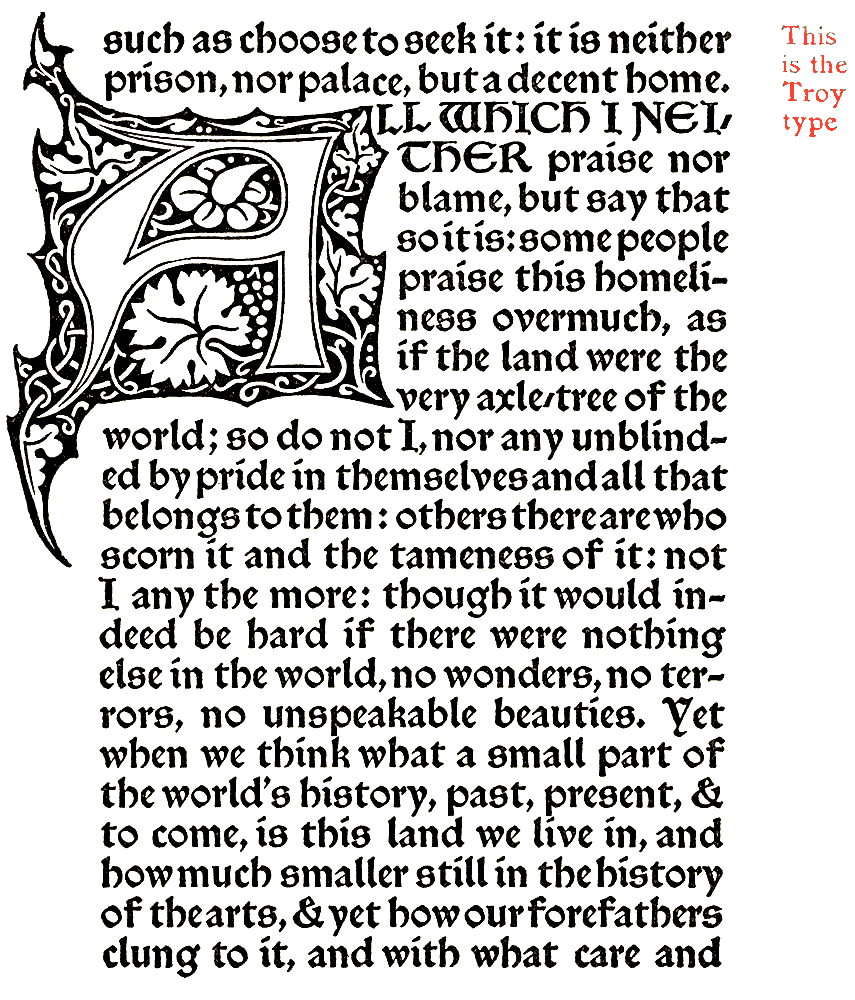

its name, in the list dated May, 1892. This Troy type,

which its designer preferred to either of the others,

shows the influence of the beautiful early types of Peter Schoeffer of

Mainz,

Gunther Zainer of Augsburg, and Anthony Koburger of Nuremberg; but,

even more

than the Golden type, it has a strong character of its own, which

differs

largely from that of any mediæval fount. It has recently been pirated

abroad,

and is advertised by an enterprising German firm as 'Die amerikanische

Triumph-Gothisch.' The Golden type has perhaps fared worse in being

remodelled

in the United States, whence, with much of its character lost, it has

found its

way back to England under the names 'Venetian,' 'Italian,' and

'Jenson.' It is

strange that no one has yet had the good sense to have the actual type

of Nicholas

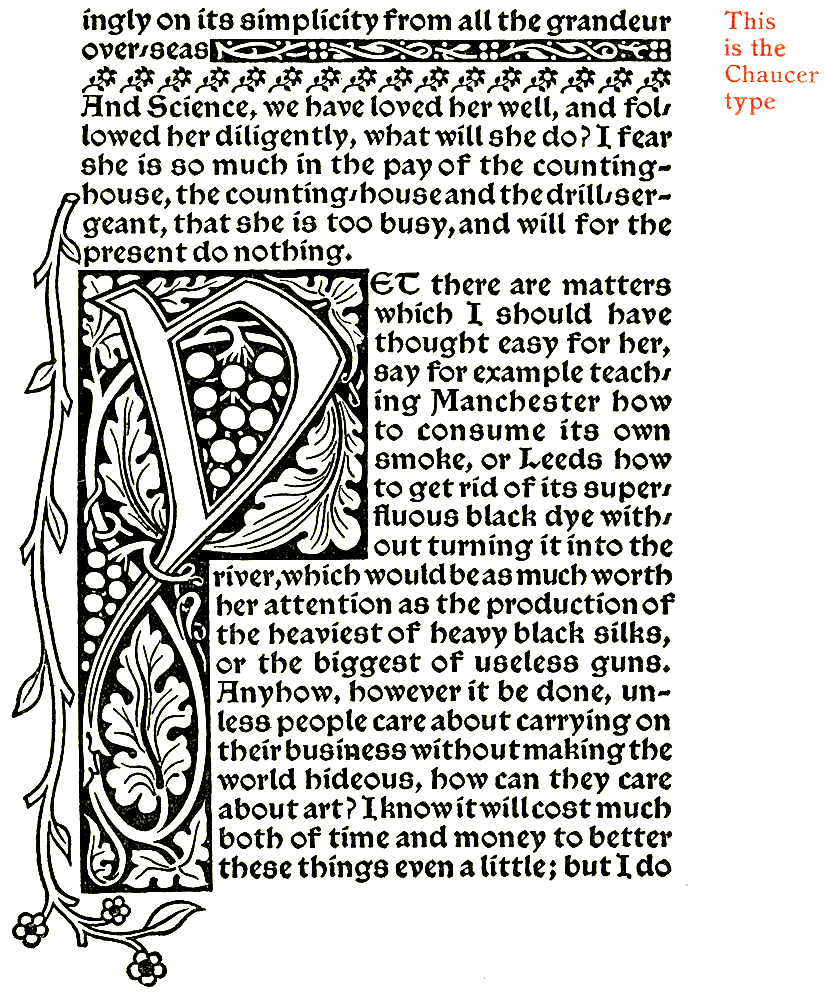

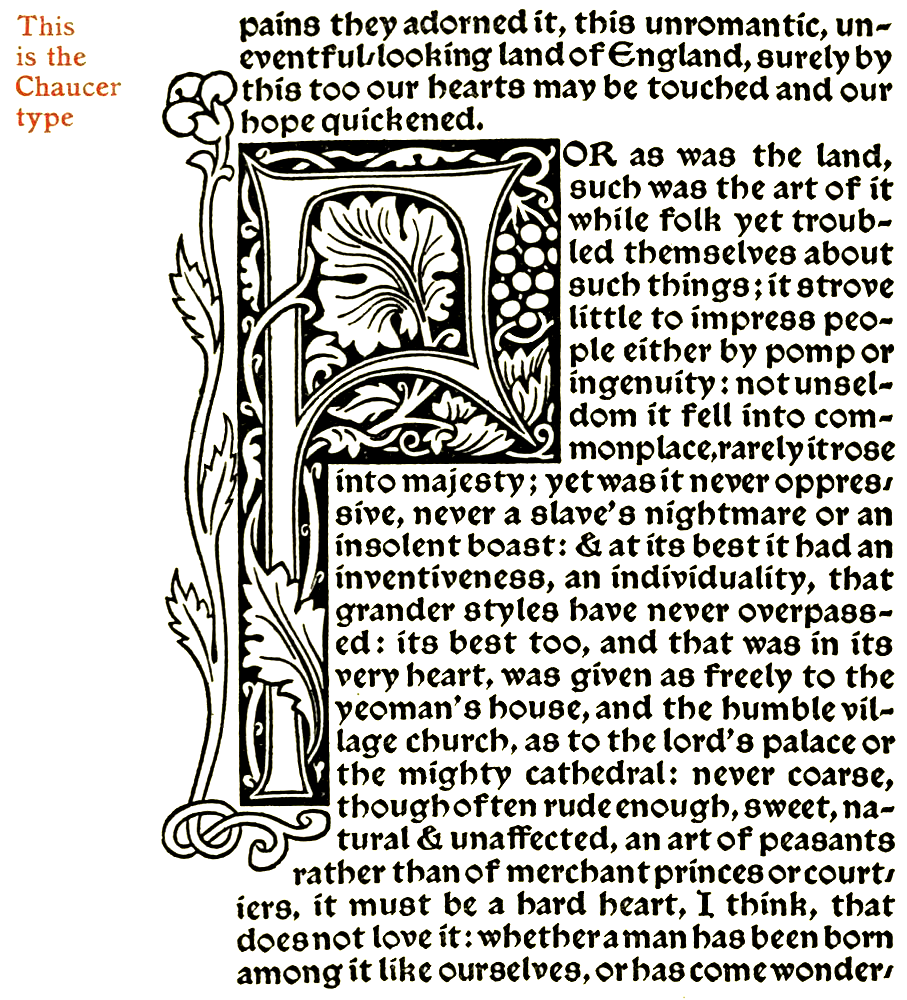

Jenson reproduced. The third type

used at the Kelmscott Press, called the 'Chaucer,'

differs from the Troy type only in size, being Pica instead of Great

Primer. It

was cut by Mr. Prince between February and May, 1892, and was ready in

June.

Its first appearance is in the list of chapters and glossary of The

Recuyell of

the Historyes of Troye, which was issued on November 24th, 1892. On June 2nd of

that year, William Morris wrote to Mr. Prince: 'I believe

in about three months' time I shall be ready with a new set of sketches

for a

fount of type on English body.' These sketches were not forthcoming;

but on

Nov. 5th, 1892, he bought a copy of Augustinus De Civitate Dei, printed

at the

Monastery of Subiaco near Rome by Sweynheym and Pannartz, with a rather

compressed type, which appears in only three known books. He at once

designed a

lower case alphabet on this model, but was not satisfied with it and

did not

have it cut. This was his last actual experiment in the designing of

type,

though he sometimes talked of designing a new fount, and of having the

Golden

type cut in a larger size. Next in

importance to the type are the initials, borders, and ornaments

designed by William Morris. The first book contains a single recto

border and

twenty different initials. In the next book, Poems by the Way, the

number of

different initials is fifty-nine. These early initials, many of which

were soon

discarded, are for the most part suggestive, like the first border, of

the

ornament in Italian manuscripts of the fifteenth century. In Art and Craft of

Printing,

by William Morris 5 Blunt's Love

Lyrics there are seven letters of a new alphabet, with

backgrounds of naturalesque grapes and vine leaves, the result of a

visit to

Beauvais, where the great porches are carved with vines, in August,

1891. From

that time onwards fresh designs were constantly added, the tendency

being

always towards larger foliage and lighter backgrounds, as the early

initials

were found to be sometimes too dark for the type. The total number of

initials

of various sizes designed for the Kelmscott Press, including a few that

were

engraved but never used, is three hundred and eighty-four. Of the

letter T

alone there are no less than thirty-four varieties. The total number

of different borders engraved for the Press, including

one that was not used, but excluding the three borders designed for The

Earthly

Paradise by R. Catterson-Smith, is fifty-seven. The first book to

contain a

marginal ornament, other than these full borders, was The Defence of

Guenevere,

which has a half-border on p. 74. There are two others in the preface

to The

Golden Legend. The Recuyell of the Historyes of Troye is the first book

in

which there is a profusion of such ornament. One hundred and eight

different designs

for marginal ornaments were engraved. Besides the above-named designs,

there

are seven frames for the pictures in The Glittering Plain, one frame

for those

in a projected edition of The House of the Wolfings, nineteen frames

for the

pictures in the Chaucer (one of which was not used in the book),

twenty-eight title-pages

and inscriptions, twenty-six large initial words for the Chaucer, seven

initial

words for The Well at the World's End and The Water of the Wondrous

Isles, four

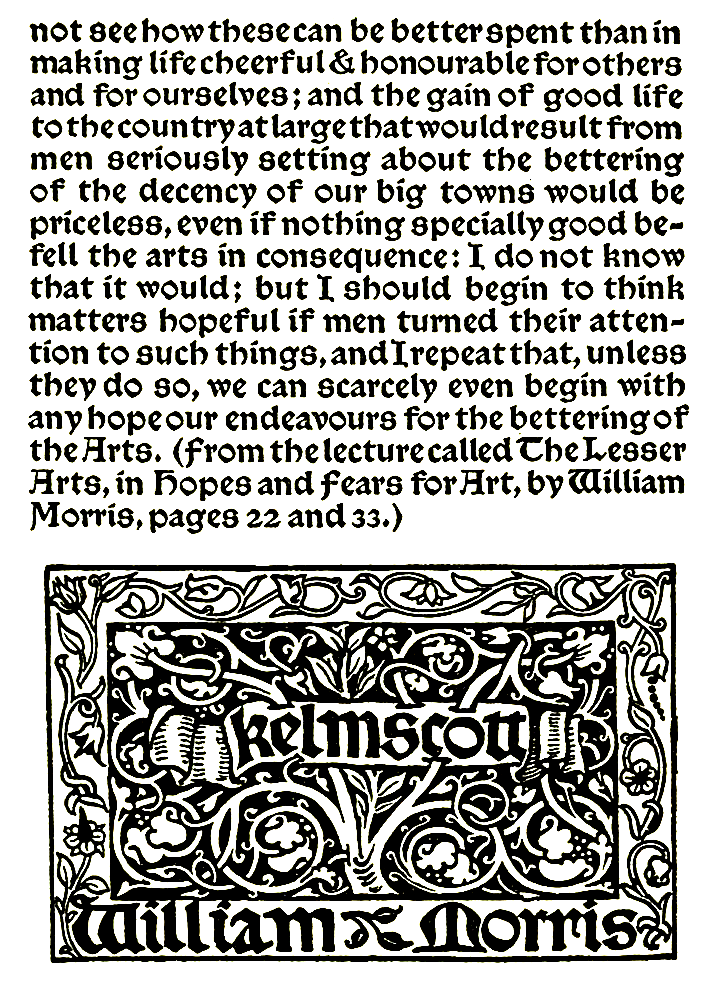

line-endings, and three printer's marks, making a total of six hundred

and

forty-four designs by William Morris, drawn and engraved within seven

years.

All the initials and ornaments that recur were printed from

electrotypes, while

most of the title-pages and initial words were printed direct from the

wood.

The illustrations by Sir Edward Burne-Jones, Walter Crane, and C. M.

Gere were

also, with one or two exceptions, printed from the wood. The original

designs

by Sir E. Burne-Jones were nearly all in pencil, and were redrawn in

ink by R.

Catterson-Smith, and in a few cases by C. Fairfax Murray; they were

then

revised by the artist and transferred to the wood by means of

photography. The

twelve designs by A. J. Gaskin for Spenser's Shepheardes Calender, the

map in

The Sundering Flood, and the thirty-five reproductions in Some German

Woodcuts

of the Fifteenth Century, were printed from process blocks. All the wood

blocks for initials, ornaments, and illustrations, were

engraved by W. H. Hooper, C. E. Keates, and W. Spielmeyer, except the

twenty-three blocks for The Glittering Plain, which were engraved by A.

Leverett,

and a few of the earliest initials, engraved by G. F. Campfield. The

whole of

these wood blocks have been sent to the British Museum, and have been

accepted

with a condition that they shall not be reproduced or printed from for

the

space of a hundred years. The electrotypes have been destroyed. In

taking this

course, which was sanctioned by William Morris when the matter was

talked of

shortly before his death, the aim of the trustees has been to keep the

series

of Kelmscott Press books as a thing apart, and to prevent the designs

becoming

stale by constant repetition. Many of them have been stolen and

parodied in

America, but in this country they are fortunately copyright. The type

remains

in the hands of the trustees, and will be used for the printing of its

designer's works, should special editions be called for. Other books of

which

he would have approved may also be printed with it; the absence of

initials and

ornament will always distinguish them sufficiently from the books

printed at

the Kelmscott Press. The nature of

the English hand-made paper used at the Press has been

described by William Morris in the foregoing article. It was at first

supplied

in sheets of which the dimensions were sixteen inches by eleven. Each

sheet had

as a watermark a conventional primrose between the initials W. M. As

stated

above, The Golden Legend was to have been the first book put in hand,

but as

only two pages could have been printed at a time, and this would have

made it

very costly, paper of double the size was ordered for this work, and

The Story

of the Glittering Plain was begun instead. This book is a small quarto,

as are

its five immediate successors, each sheet being folded twice. The last

ream of

the smaller size of paper was used on The Order of Chivalry. All the

other

volumes of that series are printed in octavo, on paper of the double

size. For

the Chaucer a stouter and slightly larger paper was needed. This has

for its

watermark a Perch with a spray in its mouth. Many of the large quarto

books

were printed on this paper, of which the first two reams were delivered

in

February, 1893. Only one other size of paper was used at the Kelmscott

Press.

The watermark of this is an Art

and Craft of

Printing, by William Morris 6 Apple,

with the

initials W.

M., as in the other two watermarks. The books printed on this paper are

The Earthly

Paradise, The Floure and the Leafe, The Shepheardes Calender, and

Sigurd the

Volsung. The last-named is a folio, and the open book shows the size of

the

sheet, which is about eighteen inches by thirteen. The first supply of

this

Apple paper was delivered on March 15, 1895. Except in the

case of Blunt's Love Lyrics, The Nature of Gothic, Biblia

Innocentium, The Golden Legend, and The Book of Wisdom and Lies, a few

copies

of all the books were printed on vellum. The six copies of The

Glittering Plain

were printed on very fine vellum obtained from Rome, of which it was

impossible

to get a second supply as it was all required by the Vatican. The

vellum for

the other books, except for two or three copies of Poems by the Way,

which were

on the Roman vellum, was supplied by H. Band of Brentford, and by W. J.

Turney

& Co. of Stourbridge. There are three complete vellum sets in

existence,

and the extreme difficulty of completing a set after the copies are

scattered,

makes it unlikely that there will ever be a fourth. The black ink which

proved

most satisfactory, after that of more than one English firm had been

tried, was

obtained from Hanover. William Morris often spoke of making his own

ink, in

order to be certain of the ingredients, but his intention was never

carried

out. The binding of

the books in vellum and in half-holland was from the

first done by J. & J. Leighton. Most of the vellum used was white,

or

nearly so, but William Morris himself preferred it dark, and the skins

showing brown

hair-marks were reserved for the binding of his own copies of the

books. The

silk ties of four colours, red, blue, yellow, and green, were specially

woven

and dyed. In the following

section fifty-two works, in sixty-six volumes, are

described as having been printed at the Kelmscott Press, besides the

two pages

of Froissart's Chronicles. It is scarcely necessary to add that only

hand presses

have been used, of the type known as 'Albion.' In the early days there

was only

one press on which the books were printed, besides a small press for

taking

proofs. At the end of May, 1891, larger premises were taken at 14,

Upper Mall,

next door to the cottage already referred to, which was given up in

June. In November,

1891, a second press was bought, as The Golden Legend was not yet half

finished, and it seemed as though the last of its 1286 pages would

never be

reached. Three years later another small house was taken, No. 14 being

still

retained. This was No. 21, Upper Mall, overlooking the river, which

acted as a

reflector, so that there was an excellent light for printing. In

January, 1895,

a third press, specially made for the work, was set up here in order

that two

presses might be employed on the Chaucer. This press has already passed

into other

hands, and the little house, with its many associations, and its

pleasant

outlook towards Chiswick and Mortlake, is now being transformed into a

granary.

The last sheet printed there was that on which are the frontispiece and

title

of this book. 14, Upper Mall,

Hammersmith, January 4, 1898. AN ANNOTATED LIST OF ALL THE BOOKS PRINTED AT THE KELMSCOTT PRESS IN THE ORDER IN WHICH THEY WERE ISSUED. This book was

set up from Nos. 81-4 of the English Illustrated Magazine,

in which it first appeared; some of the chapter headings were

re-arranged, and

a few small corrections were made in the text. A trial page, the Art and Craft of

Printing,

by William Morris 7 first printed at

the Press, was struck off on January 31, 1891, but the

first sheet was not printed until about a month later. The border was

designed

in January of the same year, and engraved by W. H. Hooper. Mr. Morris

had four

of the vellum copies bound in green vellum, three of which he gave to

friends.

Only two copies on vellum were sold, at twelve and fifteen guineas.

This was

the only book with washleather ties. All the other vellum-bound books

have silk

ties, except Shelley's Poems and Hand and Soul, which have no ties. 2. POEMS BY THE

WAY. WRITTEN BY WILLIAM MORRIS. Small 4to. Golden type.

In black and red. Border 1. 300 paper copies at two guineas, 13 on

vellum at

about twelve guineas. Dated Sept. 24, issued Oct. 20, 1891. Sold by

Reeves

& Turner. Bound in stiff vellum. This was the

first book printed at the Kelmscott Press in two colours,

and the first book in which the smaller printer's mark appeared. After

The

Glittering Plain was finished, at the beginning of April, no printing

was done

until May 11. In the meanwhile the compositors were busy setting up the

early

sheets of The Golden Legend. The printing of Poems by the Way, which

its author

first thought of calling Flores Atramenti, was not begun until July.

The poems

in it were written at various times. In the manuscript, Hafbur and

Signy is

dated February 4, 1870; Hildebrand and Hillilel, March 1, 1871; and

Love's

Reward, Kelmscott, April 21, 1871. Meeting in Winter is a song from The

Story

of Orpheus, an unpublished poem intended for The Earthly Paradise. The

last

poem in the book, Goldilocks and Goldilocks, was written on May 20,

1891, for

the purpose of adding to the bulk of the volume, which was then being

prepared.

A few of the vellum covers were stained at Merton red, yellow, indigo,

and dark

green, but the experiment was not successful. 3. THE

LOVE-LYRICS AND SONGS OF PROTEUS BY WILFRID SCAWEN BLUNT WITH THE

LOVE-SONNETS OF PROTEUS BY THE SAME AUTHOR NOW REPRINTED IN THEIR FULL

TEXT WITH

MANY SONNETS OMITTED FROM THE EARLIER EDITIONS. LONDON MDCCCXCII. Small

4to.

Golden type. In black and red. Border 1. 300 paper copies at two

guineas, none

on vellum. Dated Jan. 26, issued Feb. 27, 1892. Sold by Reeves &

Turner.

Bound in stiff vellum. This is the only

book in which the initials are printed in red. This was

done by the author's wish. 4. THE NATURE OF

GOTHIC A CHAPTER OF THE STONES OF VENICE. BY JOHN

RUSKIN. With a preface by William Morris. Small 4to. Golden type.

Border 1.

Diagrams in text. 500 paper copies at thirty shillings, none on vellum.

Dated

in preface February 15, issued March 22, 1892. Published by George

Allen. Bound

in stiff vellum. This chapter of

the Stones of Venice, which Ruskin always considered the

most important in the book, was first printed separately in 1854 as a

sixpenny

pamphlet. Mr. Morris paid more than one tribute to it in Hopes and

Fears for

Art. Of him Ruskin said in 1887, 'Morris is beaten gold.' 5. THE DEFENCE

OF GUENEVERE, AND OTHER POEMS. BY WILLIAM MORRIS. Small

4to. Golden type. In black and red. Borders 2 and 1. 300 paper copies

at two

guineas, ten on vellum at about twelve guineas. Dated April 2, issued

May 19,

1892. Sold by Reeves & Turner. Bound in limp vellum. This book was

set up from a copy of the edition published by Reeves

& Turner in 1889, the only alteration, except a few corrections,

being in

the 11th line of Summer Dawn. It is divided into three parts, the poems

suggested

by Malory's Morte d'Arthur, the poems inspired by Froissart's

Chronicles, and

poems on various subjects. The two first sections have borders, and the

last

has a half-border. The first sheet was printed on February 17, 1892. It

was the

first book bound in limp vellum, and the only one of which the title

was inscribed

by hand on the back. 6. A DREAM OF

JOHN BALL AND A KING'S LESSON. BY WILLIAM MORRIS. Small

4to. Golden type. In black and red. Borders 3a, 4, and 2. With a

woodcut

designed by Sir E. Burne-Jones. 300 paper copies at thirty shillings,

eleven on

vellum at ten guineas. Dated May 13, issued Sept. 24, 1892. Sold by

Reeves

& Turner. Bound in limp vellum. This was set up

with a few alterations from a copy of Reeves &

Turner's third edition, and the printing was begun on April 4, 1892.

The

frontispiece was redrawn from that to the first edition, and engraved

on wood

by W. H. Hooper, who engraved all Sir E. Burne-Jones' designs for the

Kelmscott

Press, except those for The Wood beyond the World and The Life and

Death of

Jason. The inscription below the figures, and the narrow border, were

designed

by Mr. Morris, and engraved with the picture on one block, which was

afterwards

used on a leaflet printed for the Ancoats Brotherhood in February,

1894. 7. THE GOLDEN

LEGEND. By Jacobus de Voragine. Translated by William

Caxton. Edited by F. S. Ellis. 3 vols. Large 4to. Golden type. Borders

5a, 5,

6a, and 7. Woodcut title and two woodcuts designed by Sir E.

Burne-Jones. 500

paper copies at five guineas, none on vellum. Dated Sept. 12, issued

Nov. 3,

1892. Published by Bernard Quaritch. Bound in half-holland, with paper

labels

printed in the Troy type. In July, 1890,

when only a few letters of the Golden type had been cut,

Mr. Morris bought a copy of this book, printed by Wynkyn de Worde in

1527. He

soon afterwards determined to print it, and on Sept. 11 entered into a

formal

agreement with Mr. Quaritch for its publication. It was only an

unforeseen

difficulty about the size of the first stock of paper that led to The

Golden

Legend not being the first book put in hand. It was set up from a

transcript of

Caxton's first edition, lent by the Syndics of the Cambridge University

Library

for the purpose. A trial page was got out in March, 1891, and 50 pages

were in

type by May 11, the day on which the first sheet was printed. The first

volume

was finished, with the exception of the illustrations and the

preliminary

matter, in Oct., 1891. The two illustrations and the title (which was

the first

woodcut title designed by Mr. Morris) were not engraved until June and

August,

1892, when the third volume was approaching completion. About half a

dozen

impressions of the illustrations were pulled on vellum. A slip asking

owners of

the book not to have it bound with pressure, nor to have the edges cut

instead

of merely trimmed, was inserted in each copy. 8. THE RECUYELL

OF THE HISTORYES OF TROYE. By Raoul Lefevre. Translated

by William Caxton. Edited by H. Halliday Sparling. 2 vols. Large 4to.

Troy

type, with table of chapters and glossary in Chaucer type. In black and

red.

Borders 5a, 5, and 8. Woodcut title. 300 paper copies at nine guineas,

five on

vellum at eighty pounds. Dated Oct. 14, issued Nov. 24, 1892. Published

by

Bernard Quaritch. Bound in limp vellum. This book, begun

in February, 1892, is the first book printed in Troy

type, and the first in which Chaucer type appears. It is a reprint of

the first

book printed in English. It had long been a favourite with William

Morris, who

designed a great quantity of initials and ornaments for it, and wrote

the

following note for Mr. Quaritch's catalogue: 'As to the matter of the

book, it

makes a thoroughly amusing story, instinct with mediæval thought and

manners.

For though written at the end of the Middle Ages and dealing with

classical

mythology, it has in it no token of the coming Renaissance, but is

merely

mediæval. It is the last issue of that story of Troy which through the

whole of

the Middle Ages had such a hold on men's imaginations; the story built

up from

a rumour of the Cyclic Poets, of the heroic City of Troy, defended by

Priam and

his gallant sons, led by Hector the Preux Chevalier, and beset by the

violent

and brutal Greeks, who were looked on as the necessary machinery for

bringing

about the undeniable tragedy of the fall of the city. Surely this is

well worth

reading, if only as a piece of undiluted mediævalism.' 2000 copies of a

4to

announcement, with specimen pages, were printed at the Kelmscott Press

in

December, 1892, for distribution by the publisher. 9. BIBLIA

INNOCENTIUM: BEING THE STORY OF GOD'S CHOSEN PEOPLE BEFORE THE

COMING OF OUR LORD JESUS CHRIST UPON EARTH, WRITTEN ANEW FOR CHILDREN

BY J. W. MACKAIL,

SOMETIME FELLOW OF BALLIOL COLLEGE, OXFORD. 8vo. Border 2. 200 on paper

at a guinea,

none on vellum. Dated Oct. 22, issued Dec. 9, 1892. Sold by Reeves

& Turner.

Bound in stiff vellum. This was the

last book issued in stiff vellum except Hand and Soul, and

the last with untrimmed edges. It was the first book printed in 8vo. 10. THE HISTORY

OF REYNARD THE FOXE BY WILLIAM CAXTON. Reprinted from

his edition of 1481. Edited by H. Halliday Sparling. Large 4to. Troy

type, with

glossary in Chaucer type. In black and red. Borders 5a and 7. Woodcut

title.

300 on paper at three guineas, 10 on vellum at fifteen guineas. Dated

Dec. 15,

1892, issued Jan. 25, 1893. Published by Bernard Quaritch. Bound in

limp

vellum. About this book,

which was first announced as in the press in the list

dated July, 1892, William Morris wrote the following note for Mr.

Quaritch's

catalogue: 'This translation of Caxton's is one of the very best of his

works

as to style; and being translated from a kindred tongue is delightful

as mere

language. In its rude joviality, and simple and direct delineation of

character, it is a thoroughly good representative of the famous ancient

Beast

Epic.' The edges of this book, and of all subsequent books, were

trimmed in

accordance with the invariable practice of the early printers. Mr.

Morris much

preferred the trimmed edges. 11. THE POEMS OF

WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE, PRINTED AFTER THE ORIGINAL COPIES

OF VENUS AND ADONIS, 1593. THE RAPE OF LUCRECE, 1594. SONNETS, 1609.

THE

LOVER'S COMPLAINT. Edited by F. S. Ellis. 8vo. Golden type. In black

and red.

Borders 1 and 2. 500 paper copies at 25 shillings, 10 on vellum at ten

guineas.

Dated Jan. 17, issued Feb. 13, 1893. Sold by Reeves & Turner. Bound

in limp

vellum. A trial page of

this book was set up on Nov. 1, 1892. Though the number

was large, this has become one of the rarest books issued from the

Press. 12. NEWS FROM

NOWHERE: OR, AN EPOCH OF REST, BEING SOME CHAPTERS FROM A UTOPIAN

ROMANCE, BY WILLIAM MORRIS. 8vo. Golden type. In black and red. Borders

9a and

4, and a woodcut engraved by W. H. Hooper from a design by C. M. Gere.

300 on

paper at two guineas, 10 on vellum at ten guineas. Dated Nov. 22, 1892,

issued

March 24, 1893. Sold by Reeves & Turner. Bound in limp vellum. The text of this

book was printed before Shakespeare's Poems and

Sonnets, but it was kept back for the frontispiece, which is a picture

of the

old manor-house in the village of Kelmscott by the upper Thames, from

which the

Press took its name. It was set up from a copy of one of Reeves &

Turner's

editions, and in reading it for the press the author made a few slight

corrections. It was the last except the Savonarola (No. 31) in which he

used

the old paragraph mark ¶ which was discarded in favour of the leaves,

which had

already been used in the two large 4to books printed in the Troy type. 13. THE ORDER OF

CHIVALRY. Translated from the French by William Caxton

and reprinted from his edition of 1484. Edited by F. S. Ellis. And

L'ORDENE DE

CHEVALERIE, WITH TRANSLATION BY WILLIAM MORRIS. Small 4to. Chaucer

type, in

black and red. Borders 9a and 4, and a woodcut designed by Sir Edward

Burne-Jones. 225 on paper at thirty shillings, 10 on vellum at ten

guineas. The

Order of Chivalry dated Nov. 10, 1892, L'Ordene de Chevalerie dated

February

24, 1893, issued April 12, 1893. Sold by Reeves & Turner. Bound in

limp

vellum. This was the

last book printed in small 4to. The last section is in 8vo.

It was the first book printed in Chaucer type. The reprint from Caxton

was

finished while News from Nowhere was in the press, and before

Shakespeare's

Poems and Sonnets was begun. The French poem and its translation were

added as

an after-thought, and have a separate colophon. Some of the three-line

initials, which were designed for The Well at the World's End, are used

in the

French poem, and this is their first appearance. The translation was

begun on

Dec. 3, 1892, and the border round the frontispiece was designed on

Feb. 13,

1893. 14. THE LIFE OF

THOMAS WOLSEY, CARDINAL ARCHBISHOP OF YORK, WRITTEN BY

GEORGE CAVENDISH. Edited by F. S. Ellis from the author's autograph MS.

8vo.

Golden type. Border 1. 250 on paper at two guineas, 6 on vellum at ten

guineas.

Dated March 30, issued May 3, 1893. Sold by Reeves & Turner. Bound

in limp

vellum. 15. THE HISTORY

OF GODEFREY OF BOLOYNE AND OF THE CONQUEST OF

IHERUSALEM. Reprinted from Caxton's edition of 1481. Edited by H.

Halliday

Sparling. Large 4to. Troy type, with list of chapter headings and

glossary in

Chaucer type. In black and red. Borders 5a and 5, and woodcut title.

300 on paper

at six guineas, 6 on vellum at 20 guineas. Dated April 27, issued May

24, 1893.

Published by William Morris at the Kelmscott Press. Bound in limp

vellum. This was the

fifth and last of the Caxton reprints, with many new

ornaments and initials, and a new printer's mark. It was first

announced as in

the press in the list dated Dec., 1892. It was the first book published

and sold

at the Kelmscott Press. An announcement and order form, with two

different

specimen pages, was printed at the Press, besides a special invoice. A

few

copies were bound in half holland, not for sale. 16. UTOPIA,

WRITTEN BY SIR THOMAS MORE. A reprint of the 2nd edition of

Ralph Robinson's translation, with a foreword by William Morris. Edited

by F.

S. Ellis. 8vo. Chaucer type, with the reprinted title in Troy type. In

black

and red. Borders 4 and 2. 300 on paper at thirty shillings, 8 on vellum

at ten guineas.

Dated August 4, issued September 8, 1893. Sold by Reeves & Turner.

Bound in

limp vellum. This book was

first announced as in the press in the list dated May 20,

1893. 17. MAUD, A

MONODRAMA. BY ALFRED LORD TENNYSON. 8vo. Golden type. In

black and red. Borders 10a and 10, and woodcut title. 500 on paper at

two

guineas, 5 on vellum not for sale. Dated Aug. 11, issued Sept. 30,

1893.

Published by Macmillan & Co. Bound in limp vellum. The borders were

specially designed for this book. They were both used

again in the Keats, and one of them appears in The Sundering Flood. It

is the

first of the 8vo books with a woodcut title. 18. GOTHIC

ARCHITECTURE: A LECTURE FOR THE ARTS AND CRAFTS EXHIBITION

SOCIETY, BY WILLIAM MORRIS. 16mo. Golden type. In black and red. 1500

on paper

at two shillings and sixpence, 45 on vellum at ten and fifteen

shillings. Bound

in half holland. This lecture was

set up at Hammersmith and printed at the New Gallery

during the Arts and Crafts Exhibition in October and November, 1893.

The first

copies were ready on October 21, and the book was twice reprinted

before the

Exhibition closed. It was the first book printed in 16mo. The four-line

initials used in it appear here for the first time. The vellum copies

were sold

during the Exhibition at ten shillings, and the price was subsequently

raised

to fifteen shillings. 19. SIDONIA THE

SORCERESS, BY WILLIAM MEINHOLD, TRANSLATED BY FRANCESCA SPERANZA

LADY WILDE. Large 4to. Golden type. In black and red. Border 8. 300

paper

copies at four guineas, 10 on vellum at twenty guineas. Dated Sept. 15,

issued

November 1, 1893. Published by William Morris. Bound in limp vellum. Before the

publication of this book a large 4to announcement and order

form was issued, with a specimen page and an interesting description of

the

book and its author, written and signed by William Morris. Some copies

were

bound in half holland, not for sale. 20. BALLADS AND

NARRATIVE POEMS BY DANTE GABRIEL ROSSETTI. 8vo. Golden

type. In black and red. Borders 4a and 4, and woodcut title. 310 on

paper at

two guineas, 6 on vellum at ten guineas. Dated Oct. 14, issued in

November,

1893. Published by Ellis & Elvey. Bound in limp vellum. This book was

announced as in preparation in the list of August 1, 1893. 21. THE TALE OF

KING FLORUS AND THE FAIR JEHANE. Translated by William

Morris from the French of the 13th century. 16mo. Chaucer type. In

black and

red. Borders 11a and 11, and woodcut title. 350 on paper at seven

shillings and

sixpence, 15 on vellum at thirty shillings. Dated Dec. 16, issued Dec.

28,

1893. Published by William Morris. Bound in half holland. This story, like

the three other translations with which it is uniform,

was taken from a little volume called Nouvelles Françoises en prose du

XIIIe

siècle. Paris, Jannet, 1856. They were first announced as in

preparation under

the heading 'French Tales' in the list dated May 20, 1893. Eighty-five

copies

of King Florus were bought by J. and M. L. Tregaskis, who had them

bound in all

parts of the world. These are now in the Rylands Library at Manchester.

22. THE STORY OF

THE GLITTERING PLAIN WHICH HAS BEEN ALSO CALLED THE

LAND OF LIVING MEN OR THE ACRE OF THE UNDYING. WRITTEN BY WILLIAM

MORRIS. Large

4to. Troy type, with list of chapters in Chaucer type. In black and

red.

Borders 12a and 12, 23 designs by Walter Crane, engraved by A.

Leverett, and a

woodcut title. 250 on paper at five guineas, 7 on vellum at twenty

pounds. Dated

Jan. 13, issued Feb. 17, 1894. Published by William Morris. Bound in

limp

vellum. Neither the

borders in this book nor six out of the seven frames round

the illustrations appear in any other book. The seventh is used round

the

second picture in Love is Enough. A few copies were bound in half

holland. 23. OF THE

FRIENDSHIP OF AMIS AND AMILE. Done out of the ancient French

by William Morris. 16mo. Chaucer type. In black and red. Borders 11a

and 11,

and woodcut title. 500 on paper at seven shillings and sixpence, 15 on

vellum

at thirty shillings. Dated March 13, issued April 4, 1894. Published by

William

Morris. Bound in half holland. A poem entitled

Amys and Amillion, founded on this story, was originally

to have appeared in the second volume of The Earthly Paradise, but,

like some

other poems announced at the same time, it was not included in the

book. 20a. SONNETS AND

LYRICAL POEMS BY DANTE GABRIEL ROSSETTI. 8vo. Golden

type. In black and red. Borders 1a and 1, and woodcut title. 310 on

paper at

two guineas, 6 on vellum at ten guineas. Dated Feb. 20, issued April

21, 1894.

Published by Ellis & Elvey. Bound in limp vellum. This book is

uniform with No. 20, to which it forms a sequel. Both

volumes were read for the press by Mr. W. M. Rossetti. 24. THE POEMS OF

JOHN KEATS. Edited by F. S. Ellis. 8vo. Golden type. In

black and red. Borders 10a and 10, and woodcut title. 300 on paper at

thirty

shillings, 7 on vellum at nine guineas. Dated March 7, issued May 8,

1894.

Published by William Morris. Bound in limp vellum. This is now

(Jan., 1898) the most sought after of all the smaller

Kelmscott Press books. It was announced as in preparation in the lists

of May

27 and August 1, 1893, and as in the press in that of March 31, 1894,

when the

woodcut title still remained to be printed. 25. ATALANTA IN

CALYDON: A TRAGEDY. BY ALGERNON CHARLES SWINBURNE. Large

4to. Troy type, with argument and dramatis personæ in Chaucer type; the

dedication and quotation from Euripides in Greek type designed by

Selwyn Image.

In black and red. Borders 5a and 5, and woodcut title. 250 on paper at

two

guineas, 8 on vellum at twelve guineas. Dated May 4, issued July 24,

1894.

Published by William Morris. Bound in limp vellum. In the vellum

copies of this book the colophon is not on the 82nd page

as in the paper copies, but on the following page. 26. THE TALE OF

THE EMPEROR COUSTANS AND OF OVER SEA. Done out of

ancient French by William Morris. 16mo. Chaucer type. In black and red.

Borders

11a and 11, both twice, and two woodcut titles. 525 on paper at seven

shillings

and sixpence, 20 on vellum at two guineas. Dated August 30, issued

Sept. 26,

1894. Published by William Morris. Bound in half holland. The first of

these stories, which was the source of The Man born to be

King, in The Earthly Paradise, was announced as in preparation in the

list of

March 31, 1894. 27. THE WOOD

BEYOND THE WORLD. BY WILLIAM MORRIS. 8vo. Chaucer type. In

black and red. Borders 13a and 13, and a frontispiece designed by Sir

E.

Burne-Jones, and engraved on wood by W. Spielmeyer. 350 on paper at two

guineas, 8 on vellum at ten guineas. Dated May 30, issued Oct. 16,

1894. Published

by William Morris. Bound in limp vellum. The borders in

this book, as well as the ten half-borders, are here used

for the first time. It was first announced as in the press in the list

of March

31, 1894. Another edition was published by Lawrence & Bullen in

1895. 28. THE BOOK OF

WISDOM AND LIES. A book of traditional stories from

Georgia in Asia. Translated by Oliver Wardrop from the original of

Sulkhan-Saba

Orbeliani. 8vo. Golden type. In black and red. Borders 4a and 4, and

woodcut

title. 250 on paper at two guineas, none on vellum. Finished Sept. 29,

issued

Oct. 29, 1894. Published by Bernard Quaritch. Bound in limp vellum. The arms of

Georgia, consisting of the Holy Coat, appear in the woodcut

title of this book. 29. THE POETICAL

WORKS OF PERCY BYSSHE SHELLEY. VOLUME I. Edited by F.

S. Ellis. 8vo. Golden type. Borders 1a and 1, and woodcut title. 250 on

paper

at twenty-five shillings, 6 on vellum at eight guineas. Not dated,

issued Nov.

29, 1894. Published by William Morris. Bound in limp vellum without

ties. Red ink is not used in this volume, though it is used in the second volume, and more sparingly in the third. Some of the half-borders designed for The Wood beyond the World reappear before the longer poems. The Shelley was first announced as in the press in the list of March 31, 1894.

29b. THE POETICAL WORKS OF PERCY BYSSHE SHELLEY. VOLUME III. Edited by F. S. Ellis. 8vo. Golden type. In black and red. 250 on paper at twenty-five shillings, 6 on vellum at eight guineas. Dated August 21, issued October 28, 1895. Published by William Morris. Bound in limp vellum without ties.

30. PSALMI

PENITENTIALES. An English rhymed version of the Seven

Penitential Psalms. Edited by F. S. Ellis. 8vo. Chaucer type. In black

and red.

300 on paper at seven shillings and sixpence, 12 on vellum at three

guineas.

Dated Nov. 15, issued Dec. 10, 1894. Published by William Morris. Bound

in half

holland. These verses

were taken from a manuscript Book of Hours written at

Gloucester in the first half of the fifteenth century, but the Rev.

Professor

Skeat has pointed out that the scribe must have copied them from an

older

manuscript, as they are in the Kentish dialect of about a century

earlier. The

half-border on p. 34 appears for the first time in this book. 31.

EPISTOLA DE CONTEMPTU MUNDI DI FRATE HIERONYMO

DA FERRARA DELLORDINE DE FRATI PREDICATORI LA QUALE MANDA AD ELENA

BUONACCORSI

SUA MADRE, PER CONSOLARLA DELLA MORTE DEL FRATELLO, SUO ZIO. Edited by

Charles Fairfax

Murray from the original autograph letter. 8vo. Chaucer type. In black

and red.

Border 1. Woodcut on title designed by C. F. Murray and engraved by W.

H.

Hooper. 150 on paper, and 6 on vellum. Dated Nov. 30, ready Dec. 12,

1894. Bound

in half holland. This little book

was printed for Mr. C. Fairfax Murray, the owner of the

manuscript, and was not for sale in the ordinary way. The colophon is

in

Italian, and the printer's mark is in red. 32. THE TALE OF

BEOWULF. Done out of the Old English tongue by William

Morris and A. J. Wyatt. Large 4to. Troy type, with argument,

side-notes, list

of persons and places, and glossary in Chaucer type. In black and red.

Borders

14a and 14, and woodcut title. 300 on paper at two guineas, 8 on vellum

at ten

pounds. Dated Jan. 10, issued Feb. 2, 1895. Published by William

Morris. Bound

in limp vellum. The borders in

this book were only used once again, in the Jason. A Note

to the Reader printed on a slip in the Golden type was inserted in each

copy.

Beowulf was first announced as in preparation in the list of May 20,

1893. The

verse translation was begun by Mr. Morris, with the aid of Mr. Wyatt's

careful

paraphrase of the text, on Feb. 21, 1893, and finished on April 10,

1894, but

the argument was not written by Mr. Morris until Dec. 10, 1894. 33. SYR

PERECYVELLE OF GALES. Overseen by F. S. Ellis, after the edition

edited by J. O. Halliwell from the Thornton MS. in the Library of

Lincoln

Cathedral. 8vo. Chaucer type. In black and red. Borders 13a and 13, and

a

woodcut designed by Sir E. Burne-Jones. 350 on paper at fifteen

shillings, 8 on

vellum at four guineas. Dated Feb. 16, issued May 2, 1895. Published by

William

Morris. Bound in limp vellum. This is the

first of the series to which Sire Degrevaunt and Syr

Isumbrace belong. They were all reprinted from the Camden Society's

volume of

1844, which was a favourite with Mr. Morris from his Oxford days. Syr

Perecyvelle

was first announced in the list of Dec. 1, 1894. The shoulder-notes

were added

by Mr. Morris. 34. THE LIFE AND

DEATH OF JASON, A POEM. BY WILLIAM MORRIS. Large 4to.

Troy type, with a few words in Chaucer type. In black and red. Borders

14a and

14, and two woodcuts designed by Sir E. Burne-Jones and engraved on

wood by W.

Spielmeyer. 200 on paper at five guineas, 6 on vellum at twenty

guineas. Dated

May 25, issued July 5, 1895. Published by William Morris. Bound in limp

vellum. This book,

announced as in the press in the list of April 21, 1894,

proceeded slowly, as several other books, notably the Chaucer, were

being

printed at the same time. The text, which had been corrected for the

second edition

of 1868, and for the edition of 1882, was again revised by the author.

The

line-fillings on the last page were cut on metal for this book, and

cast like

type. 35. CHILD

CHRISTOPHER AND GOLDILIND THE FAIR. BY WILLIAM MORRIS. 2 vols.

16mo. Chaucer type. In black and red. Borders 15a and 15, and woodcut

title.

600 on paper at fifteen shillings, 12 on vellum at four guineas. Dated

July 25,

issued Sept. 25, 1895. Published by William Morris. Bound in half

holland, with

labels printed in the Golden type. The borders

designed for this book were only used once again, in Hand

and Soul. The plot of the story was suggested by that of Havelok the

Dane,

printed by the Early English Text Society. 36. HAND AND

SOUL. BY DANTE GABRIEL ROSSETTI. Reprinted from The Germ

for Messrs. Way & Williams, of Chicago. 16mo. Golden type. In black

and

red. Borders 15a and 15, and woodcut title. 300 paper copies and 11

vellum

copies for America. 225 paper copies for sale in England at ten

shillings, and

10 on vellum at thirty shillings. Dated Oct. 24, issued Dec. 12, 1895.

Bound in

stiff vellum without ties. This was the

only 16mo book bound in vellum. The English and American

copies have a slightly different colophon. The shoulder-notes were

added by Mr.

Morris. 37. POEMS CHOSEN

OUT OF THE WORKS OF ROBERT HERRICK. Edited by F. S.

Ellis, 8vo. Golden type. In black and red. Borders 4a and 4, and

woodcut title.

250 on paper at thirty shillings, 8 on vellum at eight guineas. Dated

Nov. 21,

1895, issued Feb. 6, 1896. Published by William Morris. Bound in limp

vellum. This book was

first announced as in preparation in the list of Dec. 1,

1894, and as in the press in that of July 1, 1895. 38. POEMS CHOSEN

OUT OF THE WORKS OF SAMUEL TAYLOR COLERIDGE. Edited by

F. S. Ellis. 8vo. Golden type. In black and red. Borders 13a and 13.

300 on

paper at a guinea, 8 on vellum at five guineas. Dated Feb. 5, issued

April 12,

1896. Published by William Morris. Bound in limp vellum. This book

contains thirteen poems. It was first announced as in

preparation in the list of Dec. 1, 1894, and as in the press in that of

Nov.

26, 1895. It is the last of the series to which Tennyson's Maud, and

the poems

of Rossetti, Keats, Shelley, and Herrick belong. 39. THE WELL AT

THE WORLD'S END. BY WILLIAM MORRIS. Large 4to. Double

columns. Chaucer type. In black and red. Borders 16a, 16, 17a, 17, 18a,

18, 19a

and 19, and 4 woodcuts designed by Sir E. Burne-Jones. 350 on paper at

five

guineas, 8 on vellum at twenty guineas. Dated March 2, issued June 4,

1896.

Sold by William Morris. Bound in limp vellum. This book,

delayed for various reasons, was longer on hand than any

other. It appears in no less than twelve lists, from that of Dec.,

1892, to

that of Nov. 26, 1895, as 'in the press.' Trial pages, including one in

a

single column, were ready as early as September, 1892, and the printing

began

on December 16 of that year. The edition of The Well at the World's End

published by Longmans was then being printed from the author's

manuscript at

the Chiswick Press, and the Kelmscott Press edition was set up from the

sheets

of that edition, which, though not issued until October, 1896, was

finished in

1894. The eight borders and the six different ornaments between the

columns,

appear here for the first time, but are used again in The Water of the

Wondrous

Isles, with the exception of two borders. 40. THE WORKS OF

GEOFFREY CHAUCER. Edited by F. S. Ellis. Folio. Chaucer

type, with headings to the longer poems in Troy type. In black and red.

Borders

20a to 26, woodcut title, and 87 woodcut illustrations designed by Sir

E.

Burne-Jones. 425 on paper at twenty pounds, 13 on vellum at 120

guineas. Dated

May 8, issued June 26, 1893. Published by William Morris. Bound in half

holland. The history of

this book, which is by far the most important achievement

of the Kelmscott Press, is as follows. As far back as June 11, 1891,

Mr. Morris

spoke of printing a Chaucer with a black-letter fount which he hoped to

design.

Four months later, when most of the Troy type was designed and cut, he

expressed his intention to use it first on John Ball, and then on a

Chaucer and

perhaps a Gesta Romanorum. By January 1, 1892, the Troy type was

delivered, and

early in that month two trial pages, one from The Cook's Tale and one

from Sir

Thopas, the latter in double columns, were got out. It then became

evident that

the type was too large for a Chaucer, and Mr. Morris decided to have it

re-cut

in the size known as pica. By the end of June he was thus in possession

of the

type which in the list issued in December, 1892, he named the Chaucer

type. In

July, 1892, another trial page, a passage from The Knight's Tale in

double

columns of 58 lines, was got out, and found to be satisfactory. The

idea of the

Chaucer as it now exists, with illustrations by Sir Edward Burne-Jones,

then

took definite shape. In a proof of

the first list, dated April, 1892, there is an

announcement of the book as in preparation, in black-letter, large

quarto, but

this was struck out, and does not appear in the list as printed in May,

nor yet

in the July list. In that for Dec., 1892, it is announced for the first

time as

to be in Chaucer type 'with about sixty designs by E. Burne-Jones.' The

next

list, dated March 9, 1893, states that it will be a folio and that it

is in the

press, by which was meant that a few pages were in type. In the list

dated Aug.

1, 1893, the probable price is given as twenty pounds. The next four

lists

contain no fresh information, but on Aug. 17, 1894, nine days after the

first

sheet was printed, a notice was sent to the trade that there would be

325

copies at twenty pounds and about sixty woodcuts designed by Sir Edward

Burne-Jones. Three months later it was decided to increase the number

of

illustrations to upwards of seventy, and to print another 100 copies of

the

book. A circular letter was sent to subscribers on Nov. 14, stating

this and

giving them an opportunity of cancelling their orders. Orders were not

withdrawn, the extra copies were immediately taken up, and the list for

Dec. 1,

1894, which is the first containing full particulars, announces that

all paper

copies are sold. Mr. Morris began

designing his first folio border on Feb. 1, 1893, but

was dissatisfied with the design and did not finish it. Three days

later he

began the vine border for the first page, and finished it in about a

week, together

with the initial word 'Whan,' the two lines of heading, and the frame

for the

first picture, and Mr. Hooper engraved the whole of these on one block.

The

first picture was engraved at about the same time. A specimen of the

first page

(differing slightly from the same page as it appears in the book) was

shown at

the Arts and Crafts Exhibition in October and November, 1893, and was

issued to

a few leading booksellers, but it was not until August 8, 1894, that

the first

sheet was printed at 14, Upper Mall. On Jan. 8, 1895, another press was

started

at 21, Upper Mall, and from that time two presses were almost

exclusively at work

on the Chaucer. By Sept. 10 the last page of The Romaunt of the Rose

was

printed. In the middle of Feb., 1896, Mr. Morris began designing the

title. It

was finished on the 27th of the same month and engraved by Mr. Hooper

in March.

On May 8, a year and nine months after the printing of the first sheet,

the

book was completed. On June 2 the first two copies were delivered to

Sir Edward

Burne-Jones and Mr. Morris. Mr. Morris's copy is now at Exeter College,

Oxford,

with other books printed at the Kelmscott Press. Besides the

eighty-seven illustrations designed by Sir Edward

Burne-Jones, and engraved by W. H. Hooper, the Chaucer contains a

woodcut

title, fourteen large borders, eighteen different frames round the

illustrations, and twenty-six large initial words designed for the book

by

William Morris. Many of these were engraved by C. E. Keates, and others

by W.

H. Hooper and W. Spielmeyer. In Feb., 1896, a

notice was issued respecting special bindings, of which

Mr. Morris intended to design four. Two of these were to have been

executed

under Mr. Cobden-Sanderson's direction at the Doves Bindery, and two by

Messrs.

J. & J. Leighton. But the only design that he was able to complete

was for

a full white pigskin binding, which has now been carried out at the

Doves

Bindery on forty-eight copies, including two on vellum. 41. THE EARTHLY

PARADISE. BY WILLIAM MORRIS. VOLUME I. PROLOGUE: THE WANDERERS.

MARCH: ATALANTA'S RACE. THE MAN BORN TO BE KING. Medium 4to. Golden

type. In

black and red. Borders 27a, 27, 28a, and 28, and woodcut title. 225 on

paper at

thirty shillings, 6 on vellum at seven guineas. Dated May 7, issued

July 24,

1896. Published by William Morris. Bound in limp vellum. This was the first book printed on the paper with the apple watermark. The seven other volumes followed it at intervals of a few months. None of the ten borders used in The Earthly Paradise appear in any other book. The four different half-borders round the poems to the months are also not used elsewhere. The first border was designed in June, 1895. 41a. THE EARTHLY PARADISE. BY WILLIAM MORRIS. VOLUME II. APRIL: THE DOOM OF KING ACRISIUS. THE PROUD KING. Medium 4to. Golden type. In black and red. Borders 29a, 29, 28a, and 28. 225 on paper at thirty shillings, 6 on vellum at seven guineas. Dated June 24, issued Sept. 17, 1896. Published by William Morris. Bound in limp vellum.

41b. THE EARTHLY

PARADISE. BY WILLIAM MORRIS. VOLUME III. MAY: THE STORY

OF CUPID AND PSYCHE. THE WRITING ON THE IMAGE. JUNE: THE LOVE OF

ALCESTIS. THE

LADY OF THE LAND. Medium 4to. Golden type. In black and red. Borders

30a, 30,

27a, 27, 28a, 28, 29a, and 29. 225 on paper at thirty shillings, 6 on

vellum at

seven guineas. Dated Aug. 24, issued Dec. 5, 1896. Published at the

Kelmscott

Press. Bound in limp vellum. 41c. THE EARTHLY

PARADISE. BY WILLIAM MORRIS. VOLUME IV. JULY: THE SON

OF CROESUS. THE WATCHING OF THE FALCON. AUGUST: PYGMALION AND THE

IMAGE. OGIER THE

DANE. Medium 4to. Golden type. In black and red. Borders 31a, 31, 29a,

29, 28a,

28, 30a, and 30. Dated Nov. 25, 1896, issued Jan. 22, 1897. Published

at the

Kelmscott Press. Bound in limp vellum. 41d. THE EARTHLY

PARADISE. BY WILLIAM MORRIS. VOLUME V. SEPTEMBER: THE

DEATH OF PARIS. THE LAND EAST OF THE SUN AND WEST OF THE MOON. OCTOBER:

THE

STORY OF ACONTIUS AND CYDIPPE. THE MAN WHO NEVER LAUGHED AGAIN. Medium

4to.

Golden type. In black and red. Borders 29a, 29, 27a, 27, 28a, 28, 31a,

and 31.

Finished Dec. 24, 1896, issued Mar. 9, 1897. Published at the Kelmscott

Press.

Bound in limp vellum. 41e. THE EARTHLY

PARADISE. BY WILLIAM MORRIS. VOLUME VI. NOVEMBER: THE

STORY OF RHODOPE. THE LOVERS OF GUDRUN. Medium 4to. Golden type. In

black and

red. Borders 27a, 27, 30a, and 30. Finished Feb. 18, issued May 11,

1897.

Published at the Kelmscott Press. Bound in limp vellum. 41f. THE EARTHLY PARADISE. BY WILLIAM MORRIS. VOLUME VII. DECEMBER: THE GOLDEN APPLES. THE FOSTERING OF ASLAUG. JANUARY: BELLEROPHON AT ARGOS. THE RING GIVEN TO VENUS. Medium 4to. Golden type. In black and red. Borders 29a, 29, 31a, 31, 30a, 30, 27a, and 27. Finished March 17, issued July 29, 1897. Published at the Kelmscott Press. Bound in limp vellum. 41g. THE EARTHLY

PARADISE. BY WILLIAM MORRIS. VOLUME VIII. FEBRUARY: BELLEROPHON

IN LYCIA. THE HILL OF VENUS. EPILOGUE. L'ENVOI. Medium 4to. Golden

type. In black

and red. Borders 28a, 28, 29a, and 29. Finished June 10, issued Sept.

27, 1897.

Published at the Kelmscott Press. Bound in limp vellum. The colophon of this final volume of The Earthly Paradise contains the following note: 'The borders in this edition of The Earthly Paradise were designed by William Morris, except those on page 4 of volumes ii., iii., and iv., afterwards repeated, which were designed to match the opposite borders, under William Morris's direction, by R. Catterson-Smith; who also finished the initial words 'Whilom' and 'Empty' for The Water of the Wondrous Isles. All the other letters, borders, title-pages and ornaments used at the Kelmscott Press, except the Greek type in Atalanta in Calydon, were designed by William Morris.' 42. LAUDES

BEATAE MARIAE VIRGINIS. Latin poems taken from a Psalter

written in England about A. D. 1220. Edited by S. C. Cockerell. Large

4to. Troy

type. In black, red, and blue. 250 on paper at ten shillings, 10 on

vellum at

two guineas. Dated July 7, issued August 7, 1896. Published by William

Morris.

Bound in half holland. This was the

first book printed at the Kelmscott Press in three colours.

The manuscript from which the poems were taken was one of the most

beautiful of

the English books in Mr. Morris's possession, both as regards writing

and

ornament. No author's name is given to the poems, but after this book

was

issued the Rev. E. S. Dewick pointed out that they had already been

printed at

Tegernsee in 1579, in a 16mo volume in which they are ascribed to

Stephen

Langton. A note to this effect was printed in the Chaucer type in Dec.

28,

1896, and distributed to the subscribers. 43. THE FLOURE

AND THE LEAFE, AND THE BOKE OF CUPIDE, GOD OF LOVE, OR

THE CUCKOW AND THE NIGHTINGALE. Edited by F. S. Ellis. Medium 4to. Troy

type,

with note and colophon in Chaucer type. In black and red. 300 on paper

at ten

shillings, 10 on vellum at two guineas. Dated Aug. 21, issued Nov. 2,

1896.

Published at the Kelmscott Press. Bound in half holland. Two of the

initial words from the Chaucer are used in this book, one at

the beginning of each poem. These poems were formerly attributed to

Chaucer,

but recent scholarship has proved that The Floure and the Leafe is much

later

than Chaucer, and that The Cuckow and the Nightingale was written by

Sir Thomas

Clanvowe about A. D. 1405-10. 44. THE

SHEPHEARDES CALENDER: CONTEYNING TWELVE ÆGLOGUES, PROPORTIONABLE

TO THE TWELVE MONETHES. By Edmund Spenser. Edited by F. S. Ellis.

Medium 4to.

Golden type. In black and red. With twelve full-page illustrations by

A. J.

Gaskin. 225 on paper at a guinea, 6 on vellum at three guineas. Dated

Oct. 14,

issued Nov. 26, 1896. Published at the Kelmscott Press. Bound in half

holland. The

illustrations in this book were printed from process blocks by

Walker & Boutall. By an oversight the names of author, editor, and

artist

were omitted from the colophon. 45. THE WATER OF

THE WONDROUS ISLES. BY WILLIAM MORRIS. Large 4to.

Chaucer type, in double columns, with a few lines in Troy type at the

end of

each of the seven parts. In black and red. Borders 16a, 17a, 18a, 19,

and 19a.

250 on paper at three guineas, 6 on vellum at twelve guineas. Dated

April 1,

issued July 29, 1897. Published at the Kelmscott Press. Bound in limp

vellum. Unlike The Well

at the World's End, with which it is mainly uniform,

this book has red shoulder-notes and no illustrations. Mr. Morris began

the

story in verse on Feb. 4, 1895. A few days later he began it afresh in

alternate

prose and verse; but he was again dissatisfied, and finally began it a

third

time in prose alone, as it now stands. It was first announced as in the

press

in the list of June 1, 1896, at which date the early chapters were in

type,

although they were not printed until about a month later. The designs

for the

initial words 'Whilom' and 'Empty' were begun by William Morris shortly

before

his death, and were finished by R. Catterson-Smith. Another edition was

published by Longmans on Oct. 1, 1897. 46. TWO TRIAL

PAGES OF THE PROJECTED EDITION OF LORD BERNERS'

TRANSLATION OF FROISSART'S CHRONICLES. Folio. Chaucer type, with

heading in

Troy type. In black and red. Border 32, containing the shields of

France, the

Empire, and England and a half-border containing those of Reginald Lord

Cobham,

Sir John Chandos, and Sir Walter Manny. 160 on vellum at a guinea, none

on

paper. Dated September, issued October 7, 1897. Published at the

Kelmscott

Press. Not bound. It was the

intention of Mr. Morris to make this edition of what was

since his college days almost his favourite book, a worthy companion to

the

Chaucer. It was to have been in two volumes folio, with new cusped

initials and

heraldic ornament throughout. Each volume was to have had a large

frontispiece

designed by Sir E. Burne-Jones; the subject of the first was to have

been St.

George, that of the second, Fame. A trial page was set up in the Troy

type soon

after it came from the foundry, in Jan., 1892. Early in 1893 trial

pages were

set up in the Chaucer type, and in the list for March 9 of that year

the book

is erroneously stated to be in the press. In the three following lists

it is

announced as in preparation. In the list dated Dec. 1, 1893, and in the

three

next lists, it is again announced as in the press, and the number to be

printed

is given as 150. Meanwhile the printing of the Chaucer had been begun,

and as

it was not feasible to carry on two folios at the same time, the

Froissart

again comes under the heading 'in preparation' in the lists from Dec.

1, 1894,

to June 1, 1896. In the prospectus of the Shepheardes Calender, dated

Nov. 12,

1896, it is announced as abandoned. At that time about thirty-four

pages were

in type, but no sheet had been printed. Before the type was broken up,

on Dec. 24,

1896, 32 copies of sixteen of these pages were printed and given as a

memento

to personal friends of the poet and printer whose death now made the

completion

of the book impossible. This suggested the idea of printing two pages

for wider

distribution. The half-border had been engraved in April, 1894, by W.

Spielmeyer,

but the large border only existed as a drawing. It was engraved with

great

skill and spirit by C. E. Keates, and the two pages were printed by

Stephen

Mowlem, with the help of an apprentice, in a manner worthy of the

designs. 47. SIRE

DEGREVAUNT. Edited by F. S. Ellis after the edition printed by

J. O. Halliwell. 8vo. Chaucer type. In black and red. Borders 1a and 1,

and a

woodcut designed by Sir Edward Burne-Jones. 350 on paper at fifteen

shillings,

8 on vellum at four guineas. Dated Mar. 14, 1896, issued Nov. 12, 1897.

Published at the Kelmscott Press. Bound in half holland. This book,

subjects from which were painted by Sir Edward Burne-Jones on

the walls of The Red House, Upton, Bexley Heath, many years ago, was

always a

favourite with Mr. Morris. The frontispiece was not printed until

October,

1897, eighteen months after the text was finished. 48. SYR

YSAMBRACE. Edited by F. S. Ellis after the edition printed by J.

O. Halliwell from the MS. in the Library of Lincoln Cathedral, with

some

corrections. 8vo. Chaucer type. In black and red. Borders 4a and 4, and

a

woodcut designed by Sir Edward Burne-Jones. 350 on paper at twelve

shillings, 8

on vellum at four guineas. Dated July 14, issued Nov. 11, 1897.

Published at

the Kelmscott Press. Bound in half holland. This is the

third and last of the reprints from the Camden Society's

volume of Thornton Romances. The text was all set up and partly printed

by

June, 1896, at which time it was intended to include 'Sir Eglamour' in

the same

volume. 49. SOME GERMAN

WOODCUTS OF THE FIFTEENTH CENTURY. Being thirty-five

reproductions from books that were in the library of the late William

Morris.

Edited, with a list of the principal woodcut books in that library, by

S. C.

Cockerell. Large 4to. Golden type. In red and black. 225 on paper at

thirty

shillings, 8 on vellum at five guineas. Dated Dec. 15, 1897, issued

January 6,

1898. Published at the Kelmscott Press. Bound in half holland. Of these

thirty-five reproductions twenty-nine were all that were done

of a series chosen by Mr. Morris to illustrate a catalogue of his

library, and

the other six were prepared by him for an article in the 4th number of

Bibliographica,

part of which is reprinted as an introduction to the book. The process

blocks

(with one exception) were made by Walker & Boutall, and are of the

same

size as the original cuts. 50. THE STORY OF

SIGURD THE VOLSUNG AND THE FALL OF THE NIBLUNGS. BY

WILLIAM MORRIS. Small folio. Chaucer type, with title and headings to

the four

books in Troy type. In black and red. Borders 33a and 33, and two

illustrations

designed by Sir Edward Burne-Jones. 160 on paper at six guineas, 6 on

vellum at

twenty guineas. Dated January 19, issued February 25, 1898. Published

at the

Kelmscott Press. Bound in limp vellum. The two borders

used in this book were almost the last that Mr. Morris

designed. They were intended for an edition of The Hill of Venus, which

was to

have been written in prose by him and illustrated by Sir E.

Burne-Jones. The

foliage was suggested by the ornament in two Psalters of the last half

of the

thirteenth century in the library at Kelmscott House. The initial A at

the

beginning of the 3rd book was designed in March, 1893, for the

Froissart, and

does not appear elsewhere. An edition of

Sigurd the Volsung, which Mr. Morris justly considered his

masterpiece, was contemplated early in the history of the Kelmscott

Press. An

announcement appears in a proof of the first list, dated April, 1892,

but it

was excluded from the list as issued in May. It did not reappear until

the list

of November 26, 1895, in which, the Chaucer being near its completion,

Sigurd

comes under the heading 'in preparation,' as a folio in Troy type,

'with about

twenty-five illustrations by Sir E. Burne-Jones.' In the list of June

1, 1896,

it is finally announced as 'in the press,' the number of illustrations

is

increased to forty, and other particulars are given. Four borders had

then been

designed for it, two of which were used on pages 470 and 471 of the

Chaucer.

The other two have not been used, though one of them has been engraved.

Two

pages only were in type, thirty-two copies of which were struck off on

Jan. 11,

1897, and given to friends, with the sixteen pages of Froissart

mentioned

above. 51. THE

SUNDERING FLOOD WRITTEN BY WILLIAM MORRIS. Overseen for the

press by May Morris. 8vo. Chaucer type. In black and red. Border 10,

and a map.

300 on paper at two guineas. Dated Nov. 15, 1897, issued Feb. 25, 1898.

Published at the Kelmscott Press. Bound in half holland. This was the

last romance by William Morris. He began to write it on

Dec. 21, 1895, and dictated the final words on Sept. 8, 1896. The map

pasted

into the cover was drawn by H. Cribb for Walker & Boutall, who

prepared the

block. In the edition that Longmans are about to issue the bands of

robbers

called in the Kelmscott edition Red and Black Skinners appear correctly

as Red

and Black Skimmers. The name was probably suggested by that of the

pirates

called 'escumours of the sea' on page 154 of Godefrey of Boloyne. 52. LOVE IS

ENOUGH, OR THE FREEING OF PHARAMOND: A MORALITY. WRITTEN BY WILLIAM

MORRIS. Large 4to. Troy type, with stage directions in Chaucer type. In

black,

red, and blue. Borders 6a and 7, and two illustrations designed by Sir

Edward

Burne-Jones. 300 on paper at two guineas, 8 on vellum at ten guineas.

Dated

Dec. 11, 1897, issued Mar. 24, 1898. Published at the Kelmscott Press.

Bound in

limp vellum. This was the

second book printed in three colours at the Kelmscott

Press. As explained in the colophon, the final picture was not designed

for

this edition of Love is Enough, but for the projected edition referred

to above,

on page 5. 53. A NOTE BY

WILLIAM MORRIS ON HIS AIMS IN FOUNDING THE KELMSCOTT

PRESS, TOGETHER WITH A SHORT DESCRIPTION OF THE PRESS BY S. C.

COCKERELL, AND

AN ANNOTATED LIST OF THE BOOKS PRINTED THEREAT. Octavo. Golden type,

with five

pages in the Troy and Chaucer types. In black and red. Borders 4a and

4, and a

woodcut designed by Sir E. Burne-Jones. 525 on paper at ten shillings,

12 on

vellum at two guineas. Dated March 1, issued March 24, 1898. Published

at the

Kelmscott Press. Bound in half holland. The frontispiece

to this book was engraved by William Morris for the

projected edition of The Earthly Paradise described on page 5. This

block and

the blocks for the three ornaments on page 7 are not included among

those

mentioned on page 12 as having been sent to the British Museum. The following

items, as having a more permanent interest than most of

these announcements, merit a full description: 1. Two forms of

invitation to the annual gatherings of The Hammersmith

Socialist Society on Jan. 30, 1892, and Feb. 11, 1893. Golden type. 2. A four-page

leaflet for the Ancoats Brotherhood, with the

frontispiece from the Kelmscott Press edition of A Dream of John Ball

on the

first page. March, 1894. Golden type. 2500 copies. 3. An address to

Sir Lowthian Bell, Bart., from his employés, dated 30th

June, 1894. 8 pages. Golden type. 250 on paper and 2 on vellum. 4. A leaflet,

with fly-leaf, headed An American Memorial to Keats,

together with a form of invitation to the unveiling of his bust in

Hampstead

Parish Church on July 16, 1894. Golden type. 750 copies. 5. A slip giving

the text of a memorial tablet to Dr. Thomas Sadler, for

distribution at the unveiling of it in Rosslyn Hill Chapel, Hampstead.

Nov.,

1894. Golden type. 450 copies. 6. Scholarship