|

III

IN CARLYLE'S COUNTRY

IN crossing the sea a second time, I was more curious to see

Scotland than England, partly because I had had a good glimpse of the

latter country eleven years before, but largely because I had always

preferred the Scotch people to the English (I had seen and known more

of them in my youth), and especially because just then I was much

absorbed with Carlyle, and wanted to see with my own eyes the land and

the race from which he sprang.

I suspect anyhow I am more strongly attracted by the Celt than

by the Anglo-Saxon; at least by the individual Celt. Collectively the

Anglo-Saxon is the more impressive; his triumphs are greater; the face

of his country and of his cities is the more pleasing; the gift of

empire is his. Yet there can be no doubt, I think, that the Celts, at

least the Scotch Celts, are a more hearty, cordial, and hospitable

people than the English; they have more curiosity, more raciness, and

quicker and surer sympathies. They fuse and blend readily with another

people, which the English seldom do. In this country John Bull is

usually like a pebble in the clay; grind him and press him and bake him

as you will, he is still a pebble — a hard spot in the brick, but not

essentially a part of it.

Every close view I got of the Scotch character confirmed my

liking for it. A most pleasant episode happened to me down in Ayr. A

young man whom I stumbled on by chance in a little wood by the Doon,

during some conversation about the birds that were singing around us,

quoted my own name to me. This led to an acquaintance with the family

and with the parish minister, and gave a genuine human coloring to our

brief sojourn in Burns's country. In Glasgow I had an inside view of a

household a little lower in the social scale, but high in the scale of

virtues and excellences. I climbed up many winding stone stairs and

found the family in three or four rooms on the top floor: a father,

mother, three sons, two of them grown, and a daughter, also

grown. The father and the sons worked in an iron foundry near

by. I broke bread with them around the table in the little

cluttered kitchen, and was spared apologies as much as if we had been

seated at a banquet in a baronial hall. A Bible chapter was read after

we were seated at table, each member of the family reading a verse

alternately. When the meal was over, we went into the next

room, where all joined in singing some Scotch songs, mainly from

Burns. One of the sons possessed the finest bass voice I had ever

listened to. Its power was simply tremendous, well tempered

with the Scotch raciness and tenderness, too. He had taken the first

prize at a public singing bout, open to competition to all of Scotland.

I told his mother, who also had a voice of wonderful sweetness, that

such a gift would make her son's fortune anywhere, and found that the

subject was the cause of much anxiety to her. She feared lest it

should be the ruination of him — lest he should prostitute it to the

service of the devil, as she put it, rather than use it to the glory of

God. She said she had rather follow him to his grave than see him in

the opera or concert hall, singing for money. She wanted him to stick

to his work, and use his voice only as a pious and sacred gift. When I

asked the young man to come land sing for us at the hotel, the mother

was greatly troubled, as she afterward told me, till she learned we

were stopping at a temperance house. But the young man seemed not at

all inclined to break away from the advice of his mother. The

other son had a sweetheart who had gone to America, and he was looking

longingly thitherward. He showed me her picture, and did not at all

attempt to conceal from me, or from his family, his interest in the

original. Indeed, one would have said there were no secrets or

concealments in such a family, and the thorough unaffected piety of the

whole household, mingled with so much that was human and racy and

canny, made an impression upon me I shall not soon forget. This family

was probably an exceptional one, but it tinges all my recollections of

smoky, tall-chimneyed Glasgow.

A Scotch trait of quite another sort, and more suggestive of

Burns than of Carlyle, was briefly summarized in an item of statistics

which I used to read in one of the Edinburgh papers every Monday

morning, namely, that of the births registered during the previous

week, invariably from ten to twelve per cent, were illegitimate. The

Scotch — all classes of them — love Burns deep down in their hearts,

because he has expressed them, from the roots up, as none other has.

When I think of Edinburgh, the vision that comes before my

mind's eye is of a city presided over, and shone upon, as it were, by

two green treeless heights. Arthur's Seat is like a great irregular orb

or half-orb, rising above the near horizon there in the southeast, and

dominating city and country with its unbroken verdancy. Its

greenness seems almost to pervade the air itself — a slight radiance of

grass, there in the eastern skies. No description of Edinburgh I

had read had prepared me for the striking hill features that look down

upon it. There is a series of three hills which culminate in Arthur's

Seat, 800 feet high. Upon the first and smaller hill stands the

Castle. This is a craggy, precipitous rock, on three sides, but

sloping down into a broad gentle expanse toward the east, where the old

city of Edinburgh is mainly built, — as if it had flowed out of the

Castle as out of a fountain, and spread over the adjacent ground. Just

beyond the point where it ceases rise Salisbury Crags to a height of

570 feet, turning to the city a sheer wall of rocks like the Palisades

of the Hudson. From its brink eastward again, the ground slopes in a

broad expanse of greensward to a valley called Hunter's Bog, where I

thought the hunters were very quiet and very numerous until I saw they

were city riflemen engaged in target practice; thence it rises

irregularly to the crest of Arthur's Seat, forming the pastoral

eminence and green-shining disk to which I have referred. Along the

crest of Salisbury Crags the thick turf comes to the edge of the

precipices, as one might stretch a carpet. It is so firm and compact

that the boys cut their initials in it, on a large scale, with their

jack-knives, as in the bark of a tree. Arthur's Seat was a

favorite walk of Carlyle's during those gloomy days in Edinburgh in

1820-21. It was a mount of vision to him, and he apparently went there

every day when the weather permitted.1

There was no road in Scotland or England which I should have

been so glad to walk over as that from Edinburgh to Ecclefechan, — a

distance covered many times by the feet of him whose birth and

burial-place I was about to visit. Carlyle as a young man had walked it

with Edward Irving (the Scotch say "travel" when they mean going

afoot), and he had walked it alone, and as a lad with an elder boy, on

his way to Edinburgh college. He says in his "Reminiscences" he nowhere

else had such affectionate, sad, thoughtful, and, in fact, interesting

and salutary journeys. "No company to you but the rustle of the

grass under foot, the tinkling of the brook, or the voices of innocent,

primeval things." "I have had days as clear as Italy [as in this

Irving case]; days moist and dripping, overhung with the infinite of

silent gray, — and perhaps the latter were the preferable, in certain

moods. You had the world and its waste imbroglios of joy

and woe, of light and darkness, to yourself alone. You could

strip barefoot, if it suited better; carry shoes and socks over

shoulder, hung on your stick; clean shirt and comb were in your pocket;

omnia mea mecum porto. You lodged with shepherds,

who had clean, solid cottages; wholesome eggs, milk, oatmeal

porridge, clean blankets to their beds, and a great deal of human sense

and unadulterated natural politeness."

But how can one walk a hundred miles in cool blood without a

companion, especially when the trains run every hour, and he has a

surplus sovereign in his pocket? One saves time and consults his

ease by riding, but he thereby misses the real savor of the land. And

the roads of this compact little kingdom are so inviting, like a hard,

smooth surface covered with sand-paper! How easily the foot puts them

behind it! And the summer weather, — what a fresh under-stratum the air

has even on the warmest days! Every breath one draws has a cool,

invigorating core to it, as if there might be some unmelted, or just

melted, frost not far off.

But as we did not walk, there was satisfaction in knowing that

the engine which took our train down from Edinburgh was named Thomas

Carlyle. The cognomen looked well on the toiling, fiery-hearted,

iron-browed monster. I think its original owner would have contemplated

it with grim pleasure, especially since he confesses to having spent

some time, once, in trying to look up a shipmaster who had named his

vessel for him. Here was a hero after his own sort, a leader by the

divine right of the expansive power of steam.

The human faculties of observation have not yet adjusted

themselves to the flying train. Steam has clapped wings to our

shoulders without the power to soar; we get bird's-eye views without

the bird's eyes or the bird's elevation, distance without breadth,

detail without mass. If such speed only gave us a proportionate extent

of view, if this leisure of the eye were only mated to an equal leisure

in the glance! Indeed, when one thinks of it, how near railway

traveling, as a means of seeing a country, comes, except in the

discomforts of it, to being no traveling at all! It is like being

tied to your chair, and being jolted and shoved about at home. The

landscape is turned topsy-turvy. The eye sustains unnatural relations

to all but the most distant objects. We move in an arbitrary plane, and

seldom is anything seen from the proper point, or with the proper

sympathy of coordinate position. We shall have to wait for the air-ship

to give us the triumph over space in which the eye can share. Of this

flight south from Edinburgh on that bright summer day, I keep only the

most general impression. I recall how clean and naked the country

looked, lifted up in broad hill-slopes, naked of forests and trees and

weedy, bushy growths, and of everything that would hide or obscure its

unbroken verdancy, — the one impression that of a universe of grass, as

in the arctic regions it might be one of snow; the mountains, pastoral

solitudes; the vales, emerald vistas.

Not to be entirely cheated out of my walk, I left the train at

Lockerbie, a small Scotch market town, and accomplished the remainder

of the journey to Ecclefechan on foot, a brief six-mile pull. It was

the first day of June; the afternoon sun was shining brightly. It was

still the honeymoon of travel with me, not yet two weeks in the bonnie

land; the road was smooth and clean as the floor of a sea beach, and

firmer, and my feet devoured the distance with right good will. The

first red clover had just bloomed, as I probably should have found it

that day had I taken a walk at home; but, like the people I met, it had

a ruddier cheek than it has at home. I observed it on other occasions,

and later in the season, and noted that it had more color than in this

country, and held its bloom longer. All grains and grasses ripen slower

there than here, the season is so much longer and cooler. The pink and

ruddy tints are more common in the flowers also. The bloom of the

blackberry is often of a decided pink, and certain white, umbelliferous

plants, like yarrow, have now and then a rosy tinge. The little white

daisy ("gowan," the Scotch call it) is tipped with crimson, foretelling

the scarlet poppies, with which the grain-fields will by and by be

splashed. Prunella (self-heal), also, is of a deeper purple than with

us, and a species of cranesbill, like our wild geranium, is of a much

deeper and stronger color. On the other hand, their ripened fruits and

foliage of autumn pale their ineffectual colors beside our own.

Among the farm occupations, that which most took my eye, on

this and on other occasions, was the furrowing of the land for turnips

and potatoes; it is done with such absolute precision. It recalled

Emerson's statement that the fields in this island look as if finished

with a pencil instead of a plow, — a pencil and a ruler in this case,

the lines were so straight and so uniform. I asked a farmer at work by

the roadside how he managed it. "Ah," said he, "a Scotchman's head is

level." Both here and in England, plowing is studied like a fine art;

they have plowing matches, and offer prizes for the best furrow. In

planting both potatoes and turnips the ground is treated alike,

grubbed, plowed, cross-plowed, crushed, harrowed, chain-harrowed, and

rolled. Every sod and tuft of uprooted grass is carefully picked up by

women and boys, and burned or carted away; leaving the surface of the

ground like a clean sheet of paper, upon which the plowman is now to

inscribe his perfect lines. The plow is drawn by two horses; it is a

long, heavy tool, with double mould-boards, and throws the earth each

way. In opening the first furrow the plowman is guided by stakes;

having got this one perfect, it is used as the model for every

subsequent one, and the land is thrown into ridges as uniform and

faultless as if it had been stamped at one stroke with a die, or cast

in a mould. It is so from one end of the island to the other; the same

expert seems to have done the work in every plowed and planted field.

Four miles from Lockerbie I came to Mainhill, the name of a

farm where the Carlyle family lived many years, and where Carlyle first

read Goethe, "in a dry ditch," Froude says, and translated

"Wilhelm Meister." The land drops gently away to the south and east,

opening up broad views in these directions, but it does not seem to be

the bleak and windy place Froude describes it. The crops looked good,

and the fields smooth and fertile. The soil is rather a stubborn clay,

nearly the same as one sees everywhere. A sloping field adjoining the

highway was being got ready for turnips. The ridges had been cast; the

farmer, a courteous but serious and reserved man, was sprinkling some

commercial fertilizer in the furrows from a bag slung across his

shoulders, while a boy, with a horse and cart, was depositing stable

manure in the same furrows, which a lassie, in clogs and short skirts,

was evenly distributing with a fork. Certain work in Scotch fields

always seems to be done by women and girls, — spreading manure, pulling

weeds, and picking up sods, — while they take an equal hand with the

men in the hay and harvest fields.

The Carlyles were living on this farm while their son was

teaching school at Annan, and later at Kirkcaldy with Irving, and they

supplied him with cheese, butter, ham, oatmeal, etc., from their scanty

stores. A new farmhouse has been built since then, though the old one

is still standing; doubtless the same Carlyle's father

refers to in a letter to his son, in 1817, as being under way. The

parish minister was expected at Mainhill. "Your mother was very

anxious to have the house done before he came, or else she said she

would run over the hill and hide herself."

From Mainhill the highway descends slowly to the village of

Ecclefechan, the site of which is marked to the eye, a mile or more

away, by the spire of the church rising up against a background of

Scotch firs, which clothe a hill beyond. I soon entered the main street

of the village, which in Carlyle's youth had an open burn or creek

flowing through the centre of it. This has been covered over by some

enterprising citizen, and instead of a loitering little burn, crossed

by numerous bridges, the eye is now greeted by a broad expanse of small

cobble-stone. The cottages are for the most part very humble, and rise

from the outer edges of the pavement, as if the latter had been turned

up and shaped to make their walls. The church is a handsome brown stone

structure, of recent date, and is more in keeping with the fine fertile

country about than with the little village in its front. In the

cemetery back of it, Carlyle lies buried. As I approached, a girl

sat by the roadside, near the gate, combing her black locks and

arranging her toilet; waiting, as it proved, for her mother and

brother, who lingered in the village. A couple of boys were

cutting nettles against the hedge; for the pigs, they said, after the

sting had been taken out of them by boiling. Across the street from the

cemetery the cows of the villagers were grazing.

I must have thought it would be as easy to distinguish

Carlyle's grave from the others as it was to distinguish the man while

living, or his fame when dead; for it never occurred to me to ask in

what part of the inclosure it was placed. Hence, when I found

myself inside the gate, which opens from the Annan road through a high

stone wall, I followed the most worn path toward a new and

imposing-looking monument on the far side of the cemetery; and the edge

of my fine emotion was a good deal dulled against the marble when I

found it bore a strange name. I tried others, and still others, but was

disappointed. I found a long row of Carlyles, but he whom I sought was

not among them. My pilgrim enthusiasm felt itself needlessly

hindered and chilled. How many rebuffs could one stand? Carlyle dead,

then, was the same as Carlyle living; sure to take you down a peg or

two when you came to lay your homage at his feet.

Presently I saw "Thomas Carlyle" on a big marble slab that

stood in a family inclosure. But this turned out to be the name

of a nephew of the great Thomas. However, I had struck the right

plat at last; here were the Carlyles I was looking for, within a space

probably of eight by sixteen feet, surrounded by a high iron

fence. The latest made grave was higher and fuller than the rest,

but it had no stone or mark of any kind to distinguish it. Since

my visit, I believe, a stone or monument of some kind has been put up.

A few daisies and the pretty blue-eyed speedwell were growing amid the

grass upon it. The great man lies with his head

toward the south or southwest, with

his mother, sister, and father to the right of him, and his brother

John to the left. I was glad to learn that the high iron fence was not

his own suggestion. His father had put it around the family plat in his

lifetime. Carlyle would have liked to have had it cut down about

halfway. The whole look of this cemetery, except in the extraordinary

size of the headstones, was quite American, it being back of the

church, and separated from it, a kind of mortuary garden, instead of

surrounding it and running under it, as is the case with the older

churches. I noted here, as I did elsewhere, that the custom prevails of

putting the trade or occupation of the deceased upon his stone:

So-and-So, mason, or tailor, or carpenter, or farmer, etc.

A young man and his wife were working in a nursery of young

trees, a few paces from the graves, and I conversed with them through a

thin place in the hedge. They said they had seen Carlyle many times,

and seemed to hold him in proper esteem and reverence. The young man

had seen him come in summer and stand, with uncovered head, beside the

graves of his father and mother. "And long and reverently did he remain

there, too," said the young gardener. I learned this was Carlyle's

invariable custom: every summer did he make a pilgrimage to this spot,

and with bared head linger beside these graves. The last time he came,

which was a couple of years before he died, he was so feeble that two

persons sustained him while he walked into the cemetery. This

observance recalls a passage from his "Past and Present." Speaking of

the religious custom of the Emperor of China, he says, "He and his

three hundred millions (it is their chief punctuality) visit yearly the

Tombs of their Fathers; each man the Tomb of his Father and his Mother;

alone there in silence with what of 'worship' or of other thought there

may be, pauses solemnly each man; the divine Skies all silent over him;

the divine Graves, and this divinest Grave, all silent under him; the

pulsings of his own soul, if he have any soul, alone audible. Truly it

may be a kind of worship! Truly, if a man cannot get some glimpse into

the Eternities, looking through this portal, — through what other need

he try it?"

Carlyle's reverence and affection for his kindred were among

his most beautiful traits, and make up in some measure for the contempt

he felt toward the rest of mankind. The family stamp was never more

strongly set upon a man, and no family ever had a more original, deeply

cut pattern than that of the Carlyles. Generally, in great men who

emerge from obscure peasant homes, the genius of the family takes an

enormous leap, or is completely metamorphosed; but Carlyle keeps all

the paternal lineaments unfaded; he is his father and his mother,

touched to finer issues. That wonderful speech of his sire, which all

who knew him feared, has lost nothing in the son, but is tremendously

augmented, and cuts like a Damascus sword, or crushes like a

sledge-hammer. The strongest and finest paternal traits have survived

in him. Indeed, a little congenital rill seems to have come all the way

down from the old vikings. Carlyle is not merely Scotch; he is

Norselandic. There is a marked Scandinavian flavor in him; a touch, or

more than a touch, of the rude, brawling, bullying, hard-hitting,

wrestling viking times. The hammer of Thor antedates the hammer of his

stone-mason sire in him. He is Scotland, past and present, moral and

physical. John Knox and the Covenanters survive in him: witness his

religious zeal, his depth and solemnity of conviction, his strugglings

and agonizings, his "conversion." Ossian survives in him: behold that

melancholy retrospect, that gloom, that melodious wail. And especially,

as I have said, do his immediate ancestors survive in him, — his

sturdy, toiling, fiery-tongued, clannish yeoman progenitors: all are

summed up here; this is the net result available for literature in the

nineteenth century.

Carlyle's heart was always here in Scotland. A vague,

yearning homesickness seemed ever to possess him. "The Hill I

first saw the Sun rise over," he says in "Past and Present," "when the

Sun and I and all things were yet in their auroral hour, who can

divorce me from it? Mystic, deep as the world's centre, are the

roots I have struck into my Native Soil; no tree that grows

is rooted so." How that mournful retrospective glance

haunts his pages! His race, generation upon generation, had

toiled and wrought here amid the lonely moors, had wrestled with

poverty and privation, had wrung the earth for a scanty subsistence,

till they had become identified with the soil, kindred with it. How

strong the family ties had grown in the struggle; how the sentiment of

home was fostered! Then the Carlyles were men who lavished their heart

and conscience upon their work; they builded themselves, their days,

their thoughts and sorrows, into their houses; they leavened the soil

with the sweat of their rugged brows. When James Carlyle, his

father, after a lapse of fifty years, saw Auldgarth bridge, upon which

he had worked as a lad, he was deeply moved. When Carlyle in his

turn saw it, and remembered his father and all he had told him, he also

was deeply moved. "It was as if half a century of past time had

fatefully for moments turned back." Whatever these men touched

with their hands in honest toil became sacred to them, a page out of

their own lives. A silent, inarticulate kind of religion they put into

their work. All this bore fruit in their distinguished descendant. It

gave him that reverted, half mournful gaze; the ground was hallowed

behind him; his dead called to him from their graves. Nothing deepens

and intensifies family traits like poverty and toil and

suffering. It is the furnace heat that brings out the characters,

the pressure that makes the strata perfect. One recalls Carlyle's

grandmother getting her children up late at night, his father one of

them, to break their long fast with oaten cakes from the meal that had

but just arrived; making the fire from straw taken from their beds.

Surely, such things reach the springs of being.

It seemed eminently fit that Carlyle's dust should rest here

in his native soil, with that of his kindred, he was so thoroughly one

of them, and that his place should be next his

mother's, between whom and himself there existed such strong affection.

I recall a little glimpse he gives of his mother in a letter to his

brother John, while the latter was studying in Germany. His mother had

visited him in Edinburgh. "I had her," he writes, "at the pier of

Leith, and showed her where your ship vanished; and she looked over the

blue waters eastward with wettish eyes, and asked the dumb waves 'when

he would be back again.' Good mother."

To see more of Ecclefechan and its people, and to browse more

at my leisure about the country, I brought my wife and youngster down

from Lockerbie; and we spent several days there, putting up at the

quiet and cleanly little Bush Inn. I tramped much about the

neighborhood, noting the birds, the wild flowers, the people, the farm

occupations, etc.; going one afternoon to Scotsbrig, where the Carlyles

lived after they left Mainhill, and where both father and mother died;

one day to Annan, another to Repentance Hill, another over the hill

toward Kirtlebridge, tasting the land, and finding it good. It is an

evidence of how permanent and unchanging things are here that the house

where Carlyle was born eighty-seven years ago, and which his father

built, stands just as it did then, and looks good for several hundred

years more. In going up to the little room where he first saw the

light, one ascends the much-worn but original stone stairs, and treads

upon the original stone floors. I suspect that even the window panes in

the little window remain the same. The village is a very quiet and

humble one, paved with small cobble-stone, over which one hears the

clatter of the wooden clogs, the same as in Carlyle's early days.

The pavement comes quite up to the low, modest, stone-floored houses,

and one steps from the street directly into the most of them. When an

Englishman or a Scotchman of the humbler ranks builds a house in the

country, he either turns its back upon the highway, or places it

several rods distant from it with sheds or stables between; or else he

surrounds it with a high, massive fence, shutting out your view

entirely. In the village he crowds it to the front; continues the

street pavement into his hall, if he can; allows no fence or screen

between it and the street, but makes the communication between the two

as easy and open as possible. At least this is the case with most of

the older houses. Hence village houses and cottages in Britain are far

less private and secluded than ours, and country houses far less

public. The only feature of Ecclefechan, besides the church, that

distinguishes it from the humblest peasant village of a hundred years

ago, is the large, fine stone structure used for the public school. It

confers a sort of distinction upon the place, as if it were in some way

connected with the memory of its famous son. I think I was informed

that he had some hand in founding it. The building in which he first

attended school is a low, humble dwelling, that now stands behind the

church, and forms part of the boundary between the cemetery and the

Annan road.

From our window I used to watch the laborers on their way to

their work, the children going to school, or to the pump for water, and

night and morning the women bringing in their cows from the pasture to

be milked. In the long June gloaming the evening milking was not done

till about nine o'clock. On two occasions, the first in a brisk rain, a

bedraggled, forlorn, deeply-hooded, youngish woman came slowly through

the street, pausing here and there, and singing in wild, melancholy,

and not unpleasing strains. Her voice had a strange piercing

plaintiveness and wildness. Now and then some passer-by would toss a

penny at her feet. The pretty Edinburgh lass, her hair redder than

Scotch gold, that waited upon us at the inn, went out in the rain and

put a penny in her hand. After a few pennies had been collected the

music would stop, and the singer disappear, — to drink up her gains, I

half suspect, but do not know. I noticed that she was never treated

with rudeness or disrespect. The boys would pause and regard her

occasionally, but made no remark, or gesture, or grimace. One afternoon

a traveling show pitched its tent in the broader part of the street,

and by diligent grinding of a hand-organ summoned all the children of

the place to see the wonders. The admission was one penny, and I went

with the rest, and saw the little man, the big dog, the happy family,

and the gaping, dirty-faced, but orderly crowd of boys and girls. The

Ecclefechan boys, with some of whom I tried, not very successfully, to

scrape an acquaintance, I found a sober, quiet, modest set, shy of

strangers, and, like all country boys, incipient naturalists. If you

want to know where the birds'-nests are, ask the boys. Hence, one

Sunday afternoon, meeting a couple of them on the Annan road, I put the

inquiry. They looked rather blank and unresponsive at first; but I made

them understand I was in earnest, and wished to be shown some nests. To

stimulate their ornithology I offered a penny for the first nest,

two-pence for the second, three-pence for the third, etc., — a reward

that, as it turned out, lightened my burden of British copper

considerably; for these boys appeared to know every nest in the

neighborhood, and I suspect had just then been making Sunday calls upon

their feathered friends. They turned about, with a bashful smile, but

without a word, and marched me a few paces along the road, when they

stepped to the hedge, and showed me a hedge-sparrow's nest with young.

The mother bird was near, with food in her beak. This nest is a great

favorite of the cuckoo, and is the one to which Shakespeare refers: —

"The hedge-sparrow fed the cuckoo so long,

That it had it head bit off by it young."

The bird is not a sparrow at all, but is a warbler, closely

related to the nightingale. Then they conducted me along a pretty

by-road, and parted away the branches, and showed me a sparrow's nest

with eggs in it. A group of wild pansies, the first I had seen, made

bright the bank near it. Next, after conferring a moment soberly

together, they took me to a robin's nest, — a warm, mossy structure in

the side of the bank. Then we wheeled up another road, and they

disclosed the nest of the yellow yite, or yellow-hammer, a bird of the

sparrow kind, also upon the ground. It seemed to have a little platform

of coarse, dry stalks, like a door-stone, in front of it. In the

mean time they had showed me several nests of the hedge-sparrow, and

one of the shilfa, or chaffinch, that had been "harried," as the boys

said, or robbed. These were gratuitous and merely by the way. Then they

pointed out to me the nest of a tomtit in a disused pump that stood

near the cemetery; after which they proposed to conduct me to a

chaffinch's nest and a blackbird's nest; but I said I had already

seen several of these and my curiosity was satisfied. Did they know any

others? Yes, several of them; beyond the village, on the

Middlebie road, they knew a wren's nest with eighteen eggs in it.

Well, I would see that, and that would be enough; the coppers were

changing pockets too fast. So through the village we went, and along

the Middlebie road for nearly a mile. The boys were as grave and silent

as if they were attending a funeral; not a remark, not a smile. We

walked rapidly. The afternoon was warm, for Scotland, and the tips of

their ears glowed through their locks, as they wiped their brows. I

began to feel as if I had had about enough walking myself. "Boys,

how much farther is it?" I said. "A wee bit farther, sir;"

and presently, by their increasing pace, I knew we were nearing it. It

proved to be the nest of the willow wren, or willow warbler, an

exquisite structure, with a dome or canopy above it, the cavity lined

with feathers and crowded with eggs. But it did not contain eighteen.

The boys said they had been told that the bird would lay as many as

eighteen eggs; but it is the common wren that lays this number, — even

more. What struck me most was the gravity and silent earnestness of the

boys. As we walked back they showed me more nests that had been

harried. The elder boy's name was Thomas. He had heard of Thomas

Carlyle; but when I asked him what he thought of him, he only looked

awkwardly upon the ground.

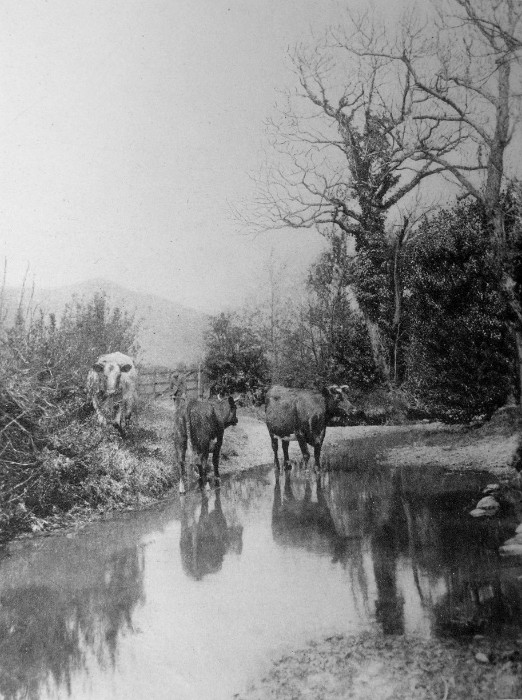

The Drinking Pool

The Drinking Pool

I had less trouble to get the opinion of an old road-mender

whom I fell in with one day. I was walking toward Repentance Hill, when

he overtook me with his "machine" (all road vehicles in Scotland are

called machines), and insisted upon my getting up beside him. He had a

little white pony, "twenty-one years old, sir," and a heavy, rattling

two-wheeler, quite as old I should say. We discoursed about roads. Had

we good roads in America? No? Had we no "metal" there, no stone? Plenty

of it, I told him, — too much; but we had not learned the art of

road-making yet. Then he would have to come "out" and show us; indeed,

he had been seriously thinking about it; he had an uncle in America,

but had lost all track of him. He had seen Carlyle many a time, "but

the people here took no interest in that man," he said; "he never done

nothing for this place." Referring to Carlyle's ancestors, he

said, "The Cairls were what we Scotch call bullies, — a set of bullies,

sir. If you crossed their path, they would murder you;" and then

came out some highly-colored tradition of the "Ecclefechan dog fight,"

which Carlyle refers to in his Reminiscences. On this occasion,

the old road-mender said, the "Cairls" had clubbed together, and

bullied and murdered half the people of the place! "No, sir, we

take no interest in that man here," and he gave the pony a sharp punch

with his stub of a whip. But he himself took a friendly interest

in the schoolgirls whom we overtook along the road, and kept picking

them up till the cart was full, and giving the "lassies" a lift on

their way home. Beyond Annan bridge we parted company, and a short walk

brought me to Repentance Hill, a grassy eminence that commands a wide

prospect toward the Solway. The tower which stands on the top is one of

those interesting relics of which this land is full, and all memory and

tradition of the use and occasion of which are lost. It is a rude

stone structure, about thirty feet square and forty high, pierced by a

single door, with the word "Repentance" cut in Old English letters in

the lintel over it. The walls are loopholed here and there for musketry

or archery. An old disused graveyard surrounds it, and the walls

of a little chapel stand in the rear of it. The conies have their holes

under it; some lord, whose castle lies in the valley below, has his

flagstaff upon it; and Time's initials are scrawled on every stone. A

piece of mortar probably three or four hundred years old, that had

fallen from its place, I picked up, and found nearly as hard as the

stone, and quite as gray and lichen-covered. Returning, I stood some

time on Annan bridge, looking over the parapet into the clear, swirling

water, now and then seeing a trout leap. Whenever the pedestrian comes

to one of these arched bridges, he must pause and admire, it is so

unlike what he is acquainted with at home. It is a real viaduct;

it conducts not merely the traveler over, it conducts the road over as

well. Then an arched bridge is ideally perfect; there is no room for

criticism, — not one superfluous touch or stroke; every stone tells,

and tells entirely. Of a piece of architecture, we can say this or

that, but of one of these old bridges this only: it satisfies every

sense of the mind. It has the beauty of poetry, and the precision of

mathematics. The older bridges, like this over the Annan, are slightly

hipped, so that the road rises gradually from either side to the key of

the arch; this adds to their beauty, and makes them look more like

things of life. The modern bridges are all level on the top, which

increases their utility. Two laborers, gossiping on the bridge, said I

could fish by simply going and asking leave of some functionary about

the castle.

Shakespeare says of the martlet, that it

"Builds in the weather on the outward wall,

Even in the force and road of casualty."

I noticed that a pair had built their nest on an iron bracket

under the eaves of a building opposite our inn, which proved to be in

the "road of casualty;" for one day the painters began scraping the

building, preparatory to giving it a new coat of paint, and the

"procreant cradle" was knocked down. The swallows did not desert the

place, however, but were at work again next morning before the painters

were. The Scotch, by the way, make a free use of paint.

They even paint their tombstones. Most of them, I observed, were

brown stones painted white. Carlyle's father once sternly drove

the painters from his door when they had been summoned by the younger

members of his family to give the house a coat "o' pent." "Ye can

jist pent the bog wi' yer ashbaket feet, for ye'll pit nane o' yer

glaur on ma door." But the painters have had their revenge at

last, and their "glaur" now covers the old man's tombstone.

One day I visited a little overgrown cemetery about a mile

below the village, toward Kirtlebridge, and saw many of the graves of

the old stock of Carlyles, among them some of Carlyle's uncles.

This name occurs very often in those old cemeteries; they were

evidently a prolific and hardy race. The name Thomas is a favorite one

among them, insomuch that I saw the graves and headstones of eight

Thomas Carlyles in the two graveyards. The oldest Carlyle tomb I saw

was that of one John Carlyle, who died in 1692. The inscription upon

his stone is as follows: —

"Heir Lyes John Carlyle of Penerssaughs, who departed this

life ye 17 of May 1692, and of age 72, and His Spouse Jannet Davidson,

who departed this life Febr. ye 7, 1708, and of age 73. Erected by

John, his son."

The old sexton, whom I frequently saw in the churchyard, lives

in the Carlyle house. He knew the family well, and had some amusing and

characteristic anecdotes to relate of Carlyle's father, the redoubtable

James, mainly illustrative of his bluntness and plainness of speech.

The sexton pointed out, with evident pride, the few noted graves the

churchyard held; that of the elder Peel being among them. He spoke of

many of the oldest graves as "extinct;" nobody owned or claimed them;

the name had disappeared, and the ground was used a second time. The

ordinary graves in these old burying-places appear to become "extinct"

in about two hundred years. It was very rare to find a date older than

that. He said the "Cairls" were a peculiar set; there was nobody like

them. You would know them, man and woman, as soon as they opened their

mouths to speak; they spoke as if against a stone wall. (Their

words hit hard.) This is somewhat like Carlyle's own view of his style.

"My style," he says in his note-book, when he was thirty-eight years of

age, "is like no other man's. The first sentence bewrays me."

Indeed, Carlyle's style, which has been so criticised, was as much a

part of himself, and as little an affectation, as his shock of coarse

yeoman hair and bristly beard and bleared eyes were a part of himself;

he inherited them. What Taine calls his barbarisms was his strong

mason sire cropping out. He was his father's son to the last drop of

his blood, a master builder working with might and main. No more

did the former love to put a rock face upon his wall than did the

latter to put the same rock face upon his sentences; and he could

do it, too, as no other writer, ancient or modern, could.

I occasionally saw strangers at the station, which is a mile

from the village, inquiring their way to the churchyard; but I was told

there had been a notable falling off of the pilgrims and visitors of

late. During the first few months after his burial, they nearly denuded

the grave of its turf; but after the publication of the Reminiscences,

the number of silly geese that came there to crop the grass was much

fewer. No real lover of Carlyle was ever disturbed by those

Reminiscences; but to the throng that run after a man because he is

famous, and that chip his headstone or carry away the turf above him

when he is dead, they were happily a great bugaboo. A most agreeable

walk I took one day down to Annan. Irving's name still exists

there, but I believe all his near kindred have disappeared. Across the

street from the little house where he was born this sign may be seen:

"Edward Irving, Flesher." While in Glasgow, I visited Irving's grave,

in the crypt of the cathedral, a most dismal place, and was touched to

see the bronze tablet that marked its site in the pavement bright and

shining, while those about it, of Sir this or Lady that, were dull and

tarnished. Did some devoted hand keep it scoured, or was

the polishing done by the many feet that paused thoughtfully above this

name? Irving would long since have been forgotten by the world had it

not been for his connection with Carlyle, and it was probably the

lustre of the latter's memory that I saw reflected in the metal that

bore Irving's name. The two men must have been of kindred genius

in many ways, to have been so drawn to each other, but Irving had far

less hold upon reality; his written word has no projectile

force. It makes a vast difference whether you burn gunpowder on a

shovel or in a gun-barrel. Irving may be said to have made a

brilliant flash, and then to have disappeared in the smoke.

Some men are like nails, easily drawn; others are like rivets,

not drawable at all. Carlyle is a rivet, well headed

in. He is not going to give way, and be forgotten soon.

People who differed from him in opinion have stigmatized him as an

actor, a mountebank, a rhetorician; but he was committed to his purpose

and to the part he played with the force of gravity. Behold how he

toiled! He says, "One monster there is in the world, — the idle

man." He did not merely preach the gospel of work; he was it, —

an indomitable worker from first to last. How he delved! How he

searched for a sure foundation, like a master builder, fighting his way

through rubbish and quicksands till he reached the rock! Each of his

review articles cost him a month or more of serious work. "Sartor

Resartus" cost him nine months, the "French Revolution" three years,

"Cromwell" four years, "Frederick" thirteen years. No surer

does the Auldgarth bridge, that his father helped build, carry the

traveler over the turbulent water beneath it, than these books convey

the reader over chasms and confusions, where before there was no way,

or only an inadequate one. Carlyle never wrote a book except to clear

some gulf or quagmire, to span and conquer some chaos. No architect or

engineer ever had purpose more tangible and definite. To further the

reader on his way, not to beguile or amuse him, was always his purpose.

He had that contempt for all dallying and toying and lightness and

frivolousness that hard, serious workers always have. He was impatient

of poetry and art; they savored too much of play and levity. His own

work was not done lightly and easily, but with labor throes and pains,

as of planting his piers in a weltering flood and chaos. The spirit of

struggling and wrestling which he had inherited was always uppermost.

It seems as if the travail and yearning of his mother had passed upon

him as a birthmark. The universe was madly rushing about him, seeking

to engulf him. Things assumed threatening and spectral shapes. There

was little joy or serenity for him. Every task he proposed to himself

was a struggle with chaos and darkness, real or imaginary. He speaks of

"Frederick" as a nightmare; the "Cromwell business" as toiling amid

mountains of dust. I know of no other man in literature with whom the

sense of labor is so tangible and terrible. That vast, grim,

struggling, silent, inarticulate array of ancestral force that lay in

him, when the burden of written speech was laid upon it, half rebelled,

and would not cease to struggle and be inarticulate. There was a

plethora of power: a channel, as through rocks, had to be made for it,

and there was an incipient cataclysm whenever a book was to be written.

What brings joy and buoyancy to other men, namely, a genial task,

brought despair and convulsions to him. It is not the effort of

composition, — he was a rapid and copious writer and speaker, — but the

pressure of purpose, the friction of power and velocity, the sense of

overcoming the demons and mud-gods and frozen torpidity he so often

refers to. Hence no writing extant is so little like writing, and

gives so vividly the sense of something done. He may

praise silence and glorify work. The unspeakable is ever present with

him; it is the core of every sentence: the inarticulate is round about

him; a solitude like that of space encompasseth him. His books are not

easy reading; they are a kind of wrestling to most persons. His style

is like a road made of rocks: when it is good, there is nothing like

it; and when it is bad, there is nothing like it! In "Past and Present"

Carlyle has unconsciously painted his own life and character in truer

colors than has any one else: "Not a May-game is this man's life, but a

battle and a march, a warfare with principalities and powers; no idle

promenade through fragrant orange groves and green, flowery spaces,

waited on by the choral Muses and the rosy Hours: it is a stern

pilgrimage through burning, sandy solitudes, through regions of

thick-ribbed ice. He walks among men; loves men with inexpressible soft

pity, as they cannot love him: but his soul dwells in

solitude, in the uttermost parts of Creation. In green oases by the

palm-tree wells, he rests a space; but anon he has to journey forward,

escorted by the Terrors and the Splendors, the Archdemons and

Archangels. All heaven, all pandemonium, are his escort." Part of the

world will doubtless persist in thinking that pandemonium furnished his

chief counsel and guide; but there are enough who think otherwise, and

their numbers are bound to increase in the future.

__________________

1 See letter to his brother John, March 9, 1821.

|