|

1999-2003 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to |

|

1999-2003 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to |

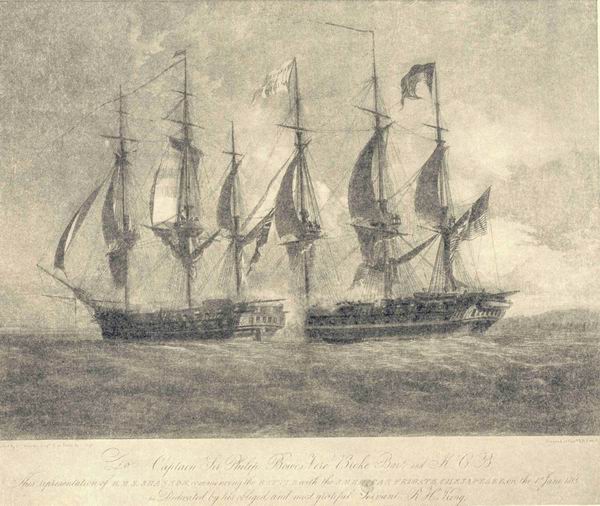

“CHESAPEAKE” AND “SHANNON”

From a Print.

New York Public Library.

BATTLE BETWEEN THE “CHESAPEAKE” AND THE “SHANNON”

Many people assembled on the shores of Hull, Nahant and Marble-head on the ill-fated day June 1, 1813, to witness the conflict between the British “Shannon” and the American “Chesapeake.” It was about luncheon time, and many of the wives complained because their husbands dropped their knives and forks when they heard the roar of the guns just north-east of Boston Light. General Broke, the English commander, desiring to retrieve the defeat of the “Macedonian,” “Guerriêre,” “Peacock” and “Java,” sent a challenge to Captain James Lawrence, who had been recently transferred to the “Chesapeake,” in which he said: “I request that you will do me the favor to meet the “Shannon,” ship to ship, to try the fortune of our respective flags. . . . I will send all other ships beyond the power of interfering with us, and meet you whenever it is most agreeable to you. . . . I will warn you should any of my friends be too nigh . . or I would sail with you, under a flag of truce, to any place you think safest from our cruisers, hauling it down when fair to begin hostilities. …You will feel it as a compliment if I say that the result of our meeting may be the most grateful service I can render to my country; and I doubt not that you, equally confident of success, will feel convinced that it is only by repeated triumphs, in even combats, that your little navy can now hope to console your country for the loss of that trade it can no longer protect.” This was certainly a coldblooded challenge, but a most fair and gallant one, and curiously enough was never received, as the “Chesapeake” sailed the morning the letter was sent.

The American vessel had been unlucky, and Captain Lawrence had not yet sufficiently trained his crew. The wharves were thronged as he prepared for sea, and as he set sail a negro from Halifax recognized a friend on board and shouted: “Good-bye, Sam! You are going to Halifax sure before you come back to Bosting.” He was promptly imprisoned. The “Chesapeake’s” crew seemed despondent and complained of not having received their prize money, whereupon the commander ordered the purser to distribute checks.

It was a beautiful day when the “Shannon” started down the Harbour, looking for her rival. Suddenly she saw her with all sails set approaching from Marblehead. The “Chesapeake” bore straight away for the Britisher, and when within pistol-shot swung into the wind, and then ensued one of the bloodiest and most terrific combats between two ships-of-war. Many broadsides were fired, and then, as the American ship swung toward the “Shannon,” General Broke and fifty of his men rushed on board and there took place a terrific hand-to-hand fight for the possession of the gangway, many of the “Chesapeake’s” crew being finally driven into the hold. The English commander was severely wounded in the head, and, propped up against the gunwale, watched the remainder of the fight. In the short space of fifteen minutes the Yankee vessel had been hit 362 times, 61 of her crew had been killed and 85 wounded, while the English vessel had been struck by 158 shot, and 83 of her seamen were dead or disabled. Lawrence was mortally wounded. His friend Samuel Livermore of Boston, who accompanied him during this fight, attempted to avenge the wounding of his commander by shooting General Broke, but the shot just missed the mark. Lawrence from below heard the firing cease for a few moments, and sent his surgeon at once to urge the men to fight on, repeating: “The colors shall wave while I live. Don’t give up the ship.” To the dismay and surprise of the people on shore the English flag was seen at the masthead of the “Chesapeake.” The Bostonians were so sure of a victory that they had prepared a banquet and Broke and his officers were to have been invited. Instead they had to watch their ship being carried away within sight of Boston Light, and those who came out in their vessels had to steer their way sadly back to Boston. The two ships then started for Halifax, their decks strewn with the dead and dying, the commander of one unconscious and the other dying. It was indeed a dismal spectacle. In one of Broke’s conscious moments he inquired about Lawrence, and hearing he was so ill he sent his own surgeon to take care of him. But Lawrence died on the way to port; his victor, practically recovered, returned to England and was knighted. He died in 1841, being under the care of a physician all the rest of his life. Captain George Crowninshield fitted out the “Henry” at his own expense to recover Lawrence’s remains, and succeeded in bringing them back to Salem, where the funeral was held. It was most impressive, among the pallbearers being Hull, Stewart and Bainbridge. The procession was led by John Saunders. Five traitors were discovered among the crew of the “Chesapeake.” The American naval signals fell into the hands of the enemy in this fight, and Bainbridge, Decatur and Hull were appointed a special committee to select a new code.