| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2018 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

|

CHAPTER

V THE

ATTEMPT TO

REACH KING EDWARD VII

LAND Towards evening

we began to pass a

number of small floe-bergs and pack-ice. We could not see very far

ahead, as

the weather was thick, so we steered more to the west to skirt this

mass of

ice. One berg had evidently been overturned, and also showed signs of

having

been aground. The Adelie penguins had become much more numerous, and we

saw an

occasional seal, but too far off to distinguish the species. During the

early

hours of January 18 we passed a few large bergs, and as morning

progressed the

wind increased, ranging between south by west and . south by east. The

ship was

pitching to a short sea, and as the water coming on board froze on

deck, and in

the stables, we made shift to keep

it out by nailing

canvas over the gaping holes in the bulwarks. Adams and Mackay were

engaged in

this very chilly job; Adams, slung in a rope over the side, every now

and then

got soaked up to the middle when the ship dipped into the sea, and as

the

temperature of the air was four degrees below freezing-point, his

tennis

trousers were not of much value for warmth in the circumstances. When

he got

too cold to continue outside, Mackay took his place, and between them

they made

a very creditable jury bulwark, which prevented the bulk of the water

rushing

into the stable. The wind continued with a force of about forty miles

an hour,

up till midday of the 19th, when it began to take off a little, and the

sky

broke blue to the northeast; the decks were thickly coated with soft

ice, and

the freshwater-pumps had frozen up hard. We were now

revelling in the

indescribable freshness of the Antarctic that seems to permeate one's

being,

and which must be responsible for that longing to go again which

assails each

returned explorer from polar regions. Our position at noon on January

19 was

latitude 73° 44' South and longitude 177° 19' East. The wind had

decreased

somewhat by midnight, and though the air remained thick and the sky

overcast

during the whole of the 20th, the weather was better. We passed through

occasional masses of floating ice and large tabular bergs, and at noon

were in

latitude 74° 45' South, longitude 179° 21' East.

VIEW OF THE GREAT ICE BARRIER On

the 21st the weather grew

clear,

the temperature was somewhat higher, and the wind light. We observed

small flights

of snow petrels and Antarctic petrels, and saw a single giant petrel

for the

first time. There were also several whales spouting in the distance.

The same

sort of weather continued throughout the day, and similar weather,

though

somewhat clearer, was experienced on the 22nd. On the morning of the

23rd we

saw some very large icebergs, and towards evening these increased in

number.

They were evidently great masses broken off the Barrier. Early in the

morning

we passed a large tilted berg, yellow with diatoms. On our port side

appeared a

very heavy pack, in which a number of large bergs were embedded. Our

course for

these three days was about due south, and we were making good headway

under

steam. We were now

keeping a sharp look-out

for the Barrier, which we expected to see at any moment. A light

south-easterly

wind blew cold, warning us that we could not be very far away from the

ice-sheet. The thermometer registered some twelve degrees of frost, but

we

hardly felt the cold, for the wind was so dry. At 9.30 A.M. on

the 23rd a low

straight line appeared ahead of the ship. It was the Barrier. After

half an

hour it disappeared from view, having evidently been only raised into

sight as

an effect of mirage, but by eleven o'clock the straight line stretching

out

east and west was in full view, and we rapidly approached it. I had

hoped to

make the Barrier about the position of what we call the Western Bight,

and at

noon we could see a point on our starboard, from which the Barrier

dropped

back. This was evidently the eastern limit of the Western Bight.

Shortly after

noon we were within a quarter of a mile of the ice-face, and

exclamations of

wonder and astonishment at the stupendous bulk of the Barrier were

drawn from

the men who had not seen it before. We slowly

steamed along, noting the

various structures of the ice, and were thankful that the weather

promised to

keep fine, for the inlet to which we were bound could not easily have

been

picked up in thick weather. The height of the Barrier about this point

ranged

from a hundred and fifty feet to two hundred feet. In the afternoon,

about

half-past one, we passed an opening in the Barrier trending in a

south-easterly

direction, but its depth was only about three-quarters of a mile. The

eastern

point had the form of the bows of a gigantic man-of-war, and reached a

height

of about two hundred and thirty feet. It was appropriately called "The

Dreadnought." As we steamed

close in to the

Barrier, watching carefully for any sign of an opening, we were able to

observe

accurately the various changes in the ice-face. In places the wall was

perfectly smooth, clean cut from the top to the water-line, in other

places it

showed signs of vertical cracks, and sometimes deep caverns appeared,

which,

illuminated by the reflected light, merged from light translucent blue

into the

deepest sapphire. At times great black patches appeared on the sides of

the

Barrier in the distance, but as we neared them they were resolved into

huge

caverns, some of which cut the water-line. One was so large that it

would have

been possible to have steamed the Nimrod

through its entrance without touching either side or its top by mast or

yard.

Looking at the Barrier from some little distance, one would imagine it

to be a

perfectly even wall of ice; when steaming along parallel with it,

however, the

impression it gave was that of a series of points, each of which looked

as

though it might be the horn of a bay. Then when the ship came abeam of

it, one

would see that the wall only receded for a. few hundred yards, and then

new

points came into view as the ship moved on. In some places a cornice of

snow

overhung the Barrier top, and again in others the vertical cracks had

widened

so that some portions of the ice-wall seemed in immediate danger of

falling.

The vagaries of light and shadow made appearances very deceptive. One

inlet we

passed had the sides thrown up in little hummocks, not more than ten or

fifteen

feet high, but until we were fairly close these irregularities had the

appearance of hills. The weather

continued fine and calm.

During the voyage of the Discovery

we

had always encountered a strong westerly current along the Barrier, but

there

was absolutely no sign of this here, and the ship was making a good

five knots.

To the northward of us lay a very heavy pack, interspersed with large

ice-bergs, one of which was over two miles long and one hundred and

fifty feet

high. This pack-ice was much heavier and more rugged than any we had

encountered on the previous expedition. Evidently there must have been

an

enormous b Baking away of ice to the eastward for as far as we could

see from

the crow's-nest, to the north and east, this ice continued About midnight

we suddenly came to

the end of a very high portion of the Barrier, and found as we followed

round

that we were entering a wide shallow bay. This must have been the inlet

where

Borchgrevink landed in 1900, but it had greatly changed since that

time. He

describes the bay as being a fairly narrow inlet. On our way east in

the Discovery in 1902 we passed an

inlet

somewhat similar, but we did not see the western end as it was obscured

by fog

at the time. There seemed to be no doubt that the Barrier had broken

away at

the entrance of this bay or inlet, and so had made it much wider and

less deep

than it was in previous years. About half a mile down the bay we

reached fast

ice. It was now about half-past twelve at night, and the southerly sun

shone in

our faces. Our astonishment was great to see beyond the six or seven

miles of

flat bay ice, which was about five or six feet thick, high rounded

ice-cliffs,

with valleys between, running in an almost east and west direction.

About four

miles to the south we saw the opening of a large valley, but could not

say

where it led. Due south of us, and rising to a height of approximately

eight

hundred feet, were steep and rounded cliffs, and behind them sharp

peaks. The

southerly sun being low, these heights threw shadows which, for some

time, had

the appearance of bare rocks. Two dark patches in the face of one of

the further

cliffs had also this appearance, but a careful observation taken with a

telescope showed them to be caverns. To the east rose a long snow slope

which

cut the horizon at the height of about three hundred feet. It had every

appearance of ice-covered land, but we could not stop then to make

certain, for

the heavy ice and bergs lying to the northward of us were setting down

into the

bay, and I saw that, if we were not to be beset, it would be necessary

to get

away at once. All round us were numbers of great whales showing their

dorsal

fins as they occasionally sounded, and on the edge of the bay-ice half

a dozen

Emperor penguins stood lazily observing us. We named this place the Bay

of

Whales, for it was a veritable playground for these monsters. We tried to

work to the eastward

so-as once more to get close to the Barrier which we could see rising

over the

top of the small bergs and pack-ice, but we found this impossible, and

so

struck northwards through an open lead and came south to the Barrier

again about

2 A.M. on the 24th. We coasted eastward along the wall of ice, always

on the

look-out for the inlet. The lashings had been taken off the motor-car,

and the

tackle rigged to hoist it out directly we got alongside the ice-foot,

to which

the Discovery had been moored; for

in

Barrier Inlet we proposed to place our winter quarters. I must leave

the narrative for a

moment at this point and refer to the reasons that made me decide on

this inlet

as the site for the winter quarters. I knew that Barrier Inlet was

practically

the beginning of King Edward VII Land, and that the actual bare land

was within

an easy sledge journey of that place, and it had the great advantage of

being

some ninety miles nearer to the South Pole than any other spot that

could be

reached with the ship. A further point of importance was that it would

be an

easy matter for the ship on its return to us to reach this part of the

Barrier,

whereas King Edward VII Land itself might quite conceivably be

unattainable if

the season was adverse. Some of my Discovery

comrades had also considered Barrier Inlet a good place at which to

winter.

After thinking carefully over the matter I had decided in favour of

wintering

on the Barrier instead of on actual land, and on the lroanya's

departure I had

sent a message to the headquarters of the expedition in London to the

effect

that, in the event of the Nimrod

not

returning at the usual time in 1908, no steps were to be taken to

provide a

relief ship to search for her in 1909, for it was only likely under

those circumstances

that she was frozen in; but that if she did not turn up with us in

1909, then

the relief expedition should start in December of that year. The point

to which

they should first direct their search was to be Barrier Inlet, and if

we were

not found there, they were to search the coast of Bing Edward VII Land.

I had

added that it would only be by stress of the most unexpected

circumstances that

the ship would be unable to return to New Zealand. However, the

best-laid schemes often

prove impracticable in polar exploration, and within a few hours our

first plan

was found impossible of fulfilment. Within thirty-six hours a second

arrangement had to be abandoned. We were steaming along westward close

to the

Barrier, and according to the chart we were due to be abreast of the

inlet

about 6 A.M., but not a sign was there of the opening. We had passed

Borchgrevink's Bight at 1 A.M., and at 8 P.M. were well past the place

where

Barrier Inlet ought to have been. The Inlet had disappeared, owing to

miles of the

Barrier having calved away, leaving a long wide bay joining up with

Borchgrevink's Inlet, and the whole was now merged into what we had

called the

Bay of Whales. This was a great disappointment to us, but we were

thankful that

the Barrier had broken away before we had made our camp on it. It was

bad

enough to try and make for a port that had been wiped off the face of

the

earth, when all the intending inhabitants were safe on board the ship,

but it

would have been infinitely worse if we had landed there whilst the

place was

still in existence, and that when the ship returned to take us off she

should

find the place gone. The thought of what might have been made me decide

then

and there that, under no circumstances, would I winter on the Barrier,

and that

wherever we did land we would secure a solid rock foundation for our

winter

home. We had two

strings to our bow, and I

decided to use the second at once and push forward towards King Edward

VII

Land. Just after 8 A.M. on the 24th we turned a corner in the Barrier,

where it

receded about half a mile, before continuing to the eastward again. The

line of

its coast here made a right angle, and the ice sloped down to sea-level

at the

apex of the angle, but the elope was too steep and too heavily

crevassed for us

to climb up and look over the surface if we had made a landing. We tied the

ship up to a fairly

large floe, and I went down to England's cabin to talk the matter over.

In the

corner where we were lying there were comparatively few pieces of

floe-ice, but

outside us lay a very heavy pack, in which several large bergs were

locked. Our

only chance was to go straight on, keeping close to the Barrier, as a

lane of

open water was left between the Barrier and the edge of the pack to the

north

of us. Sights were taken for longitude by four separate observers, and

the

positions calculated showed us we were not only well to the eastward of

the

place where Barrier Inlet was shown on the chart, but also that the

Barrier had

receded at this particular point since January 1902. About nine

o'clock we cast off from

the floe and headed the ship to the eastward, again keeping a few

hundred yards

off the Barrier, for just here the cliff overhung, and if a fall of ice

had

occurred while we were close in the results would certainly have been

disastrous for us. I soon saw that we would not be able to make much

easting in

this way, for the Barrier was now trending well to the north-east, and

right

ahead of us lay an impenetrably close pack, set with huge icebergs. By

10 A.M..

we were close to the pack and found that it was pressed bard against

the

Barrier edge, and, what was worse, the whole of the northern pack and

bergs at

this spot were drifting in towards the Barrier. The seriousness of this

situation can be well realised by the reader if he imagines for a

moment that

he is in a small boat right under the vertical white cliffs of Dover;

that

detached cliffs are moving in from seaward slowly but surely, with

stupendous

force and resistless power, and that it will only be a question of

perhaps an

hour or two before the two masses come into contact with his tiny craft

between.  PUSHING THROUGH HEAVY FLOES IN THE ROSS SEA, THE DARK LINE ON THE HORIZON IS A "WATER SKY," AND INDICATES THE EXISTENCE OF OPEN SEA There

was nothing for it but

to

retrace our way and try some other route. Our position was latitude 78°

20'

South and longitude 162° 14' West when the ship turned. The pack had

already

moved inside the point of the cliff where we had lain in open water at

eight

o'clock, but by steaming hard and working in and out of the looser

floes we

just managed to pass the point at 11.20 A.M. with barely fifty yards of

open

water to spare between the Barrier and the pack. I breathed more

freely when we

passed this zone of immediate danger, for there were two or three

hundred yards

of clear water now between us and the pack. We were right under the

Barrier

cliff, which was here over two hundred and fifty feet high, and our

course lay

well to the south of west, being roughly southwest true; so as we moved

south

more quickly than the advancing ice we were able to keep close along

the

Barrier, which gradually became lower, until about three o'clock we

were

abreast of some tilted bergs at the eastern entrance of the Bay of

Whales.

There was a peculiar light which rendered distances and the forms of

objects

very deceptive, and a great deal of mirage, which made things appear

much

higher than they actually were. This was particularly noticeable in the

case of

the pack-ice; the whole northern and western sea seemed crowded with

huge

icebergs, though in reality there was only heavy pack. The penguins

that we had

seen the previous night were still at the same place, and when a couple

of

miles away from us they loomed up as if they were about six feet high.

This bay

ice, on which many seals were lying, was cracking, and would soon float

away,

with one or two large icebergs embedded in it.  FLIGHT OF ANTARCTIC PETRELS When I came up

again, just before

noon on January 25, I found that my hopes for a clear run were vain.

Our noon

observations showed that we were well to the north of the Barrier, and

still to

the westward of the point we had reached the previous morning before we

had

been forced to turn round. The prospect of reaching King Edward VII

Land seemed

to grow more remote every ensuing hour. There was high hummocky pack

interspersed with giant icebergs to the east and south of the ship, and

it was

obvious that the whole sea between Cape Colbeck and the Barrier at our

present

longitude must be full of ice. To the northward the strong ice blink on

the

horizon told the same tale. It seemed as if it would be impossible to

reach the

land, and the shortness of coal, the leaky condition of the ship, and

the

absolute necessity of landing all our stores and putting up the hut

before the

vessel left us made the situation an extremely anxious one for me. I

had not

expected to find Barrier Inlet gone, and, at the same time, the way to

King

Edward VII Land absolutely blocked by ice, though the latter condition

was not

unusual, for every expedition in this longitude up till 1901 had been

held up

by the pack; indeed Ross, in this locality, sailed for hundreds of

miles to the

northward along the edge of a similar pack on this meridian. It is true

that we

had steam, but the Discovery, or

even

the Yermak, the most powerful ice-breaker ever built, would have made

no

impression upon the cemented field of ice. I decided to

continue to try and

make a way to the east for at least another twenty-four hours. We

altered the

course to the north, skirting the ice as closely as possible, and

taking

advantage of the slightest trend to the eastward, at times running into

narrow

cols-de-sac in the main pack, only to find it necessary to retrace our

way

again. The wind began to freshen from the west, and the weather to

thicken. A

little choppy sea washed over the edges of the floes, and the glass was

falling. About five o'clock some heavy squalls of snow came down, and

we had to

go dead slow, for the horizon was limited at times to a radius of less

than one

hundred yards. Between the squalls it was fairly clear, and we could

make out

great numbers of long, low bergs, one of which was over five miles in

length,

though not more than forty feet high. The waves were splashing up

against the

narrow end as we passed within a couple of cables' length of the berg,

and

almost immediately afterwards another squall swept down upon us. The

weather

cleared again shortly, and we saw the western pack moving rapidly

towards us

under the influence of the wind; in some places it had already met the

main

pack. As it was most likely that we would be caught in this great mass

of ice,

and that days, or even weeks, might elapse before we could extricate

ourselves,

I reluctantly gave orders to turn the ship and make full speed out of

this dangerous

situation. I could see nothing for it except to steer for McMurdo

Sound, and

there make our winter quarters. For many reasons I would have preferred

landing

at King Edward VII Land, as that region was absolutely unknown. A

fleeting

glimpse of bare cocks and high snow slopes was all that we obtained of

it on

the Discovery expedition, and had

we

been able to establish our winter quarters there, we could have added

greatly

to the knowledge of the geography of that region. There would perhaps

have been

more difficulty in the attempt to reach the South Pole from that base,

but I

did not expect that the route from there to the Barrier surface, from

which we

could make a fair start for the Pole, would have been impracticable. I

did not

give up the destined base of our expedition without a strenuous

struggle, as

the track of the ship given in the sketch-map shows; but the forces of

these

uncontrollable ice-packs are stronger than human resolution, and a

change of

plan was forced upon us. After more

trouble with the ice we

worked into clearer water and the course was set for McMurdo Sound,

where we

arrived on January 29, and found that some twenty miles of frozen sea

separated

us from Hut Point. I decided to lie off the ice-foot for a few days at

least,

and give Nature a chance to do what we could not do with the ship, that

is, to

break up the miles of ice intervening between us and our goal. So far the

voyage had been without

accident to any of the staff, but on the morning of the 31st, when all

hands

were employed getting stores out of the after hatch, preparatory to

landing

them, a hook on the tackle slipped and, swinging suddenly across the

deck,

struck Mackintosh in the right eye. He fell on the deck in great pain,

but was

able, in a few minutes, to walk with help to England's cabin, where

Marshall

examined him. It was apparent that the sight of the eye was completely

destroyed, so he was put under chloroform, and Marshall removed the

eye, being

assisted at the operation by the other two doctors, Michell and Mackay.

It was

a great comfort to me to know that the expedition had the services of

thoroughly good surgeons. Mackintosh felt the loss of his eye keenly;

not so

much because the sight was gone, but because it meant that he could not

remain

with us in the Antarctic. He begged to be allowed to stay, but when

Marshall

explained that he might lose the sight of the other eye, unless great

care were

taken, he accepted his ill-fortune without further demur, and thus the

expedition lost, for a time, one of its most valuable members.  "NIMROD" MOORED OFF TABULAR BERGS Whilst waiting

at the ice, I thought

it as well that a small party should proceed to Hut Point, and report

on the

condition of the hut left there by the Discovery

expedition in 1904. I decided to send Adams, Joyce, and Wild, giving

Adams

instructions to get into the hut and then return the next day to the

ship. They

started off on their sixteen-mile march with plenty of provisions in

case of

being delayed, and a couple of spades. On their return, Adams reported

that

they had found the hut practically clear of snow, and the structure

quite

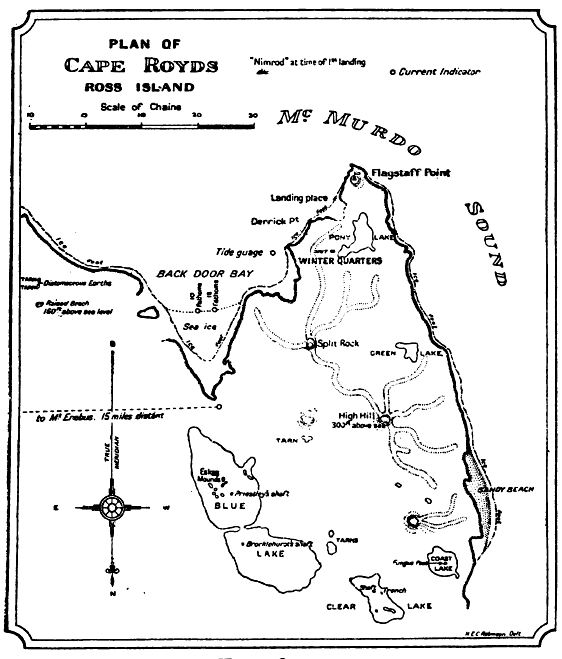

intact. On February 3 I

decided to wait no

longer at the ice face, but to seek for winter quarters on the east

coast of

Ross Island. About four o'clock we got under way and started towards

Cape Barne

on the look-out for a suitable landing-place. Steaming slowly north

along the

coast we saw across the bay a long, low snow slope, connected with the

bare

rock of Cape Royds, which appeared to be a likely place for winter

quarters. About eight

o'clock I left the ship

in a boat, accompanied by Adams and Wild. Proceeding towards the shore,

we used

the hand-lead at frequent intervals until we came up against fast ice.

This

covered the whole of the small bay from the corner of Flagstaff Point

(as we

afterwards named the seaward cliff at the southern end of Cape Royds)

to Cape

Barne to the southward. Close up to the Point the ice had broken out,

leaving a

little natural dock into wmeh we ran the boat. Adams and I scrambled

ashore,

crossing a well-defined tide-crack and going up a smooth snow-slope,

about

fifteen yards wide, at the top of which was bare rock. Hundreds of

Adelie

penguins were moving to and fro on the top of the slope, and they

greeted us

with hoarse squawks of excitement. A very brief

examination of the

vicinity of the ice-foot was sufficient to show us that Cape Royds

would be an

excellent place at which to land our stores. We therefore shoved off

again, and

skirting along the ice-foot to the south, sounded the bay and found

that the

water deepened from two fathoms close in shore to about twenty fathoms

four

hundred yards further south. After

completing these soundings we

pulled out towards the ship, which had been coming in very slowly. We

were

pulling along at a good rate when suddenly a heavy body shot out of the

water,

struck the seaman who was pulling stroke, and dropped with a thud into

the

bottom of the boat. The arrival was an Adelie penguin. It was hard to

say who

was the most astonished —

the penguin,

at the result of its leap on to what it had doubtless thought was a

rock, or

we, who so suddenly took on board this curious passenger. The sailors

in the

boat looked upon this incident as an omen of good luck. There is a

tradition

amongst seamen that the souls of old sailors, after death, occupy the

bodies of

penguins, as well as of albatrosses; this idea, however, does not

prevent the

mariners from making a hearty meal off the breasts of the former when

opportunity offers. We arrived on board at 9 P.M., and by 10 P.M. on

February 3

the Nimrod was moored to the bay

ice,

ready to land the stores. Immediately

after securing the ship

I went ashore, accompanied by the Professor, England, and Dunlop, to

choose a

place for building the hut. We passed the penguins, which were marching

solemnly to and fro, and on reaching the level land, made for a huge

boulder of

kenyte, the most conspicuous mark in the locality. I thought that we

might

build the hut under the lee of this boulder, sheltered from the

south-east wind,

but the situation had its drawbacks, as it would have entailed a large

amount

of levelling before the foundation of the hut could have been laid. We

crossed

a narrow ridge of rock just beyond the great boulder, and, turning a

little to

the right up a small valley, found an ideal spot for our winter

quarters.' The

floor of this valley was practically level and covered with a couple of

feet of

volcanic earth; at the sides the bed-rock was exposed, but a rough eye

measurement was quite sufficient to show that there would be not only

ample

room for the hut itself, but also for all the stores, and for a stable

for the

ponies. A hill right behind this little valley would serve as an

excellent

shelter to the hut from what we knew was the prevailing strong wind,

that is,

the south-easter. A glance at the illustrations will give the reader a

much

better idea of this place than will a written description, and he will

see how

admirably Nature had provided us with a protection against her own

destructive

forces. A number of seals lying on the bay ice gave promise that there

would be

no lack of fresh meat.  ADELIE PENGUINS AT CAPE ROYDS  WINTER QUARTERS With this ideal

situation for a

camp, and everything else satisfactory, including a supply of water

from a lake

right in front of our little valley, I decided that we could not do

better than

start getting our gear ashore at once. There was only one point that

gave me

any anxiety, and that was as to whether the sea would freeze over

between this

place and Hut Point in ample time for us to get across for the southern

and

western journeys in the following spring. It was also obvious that

nothing

could be done in the way of laying out depots for the next season's

work, as

directly the ship left we would be cut off from any communication with

the

lands to the south of us, by sea and by land, for the heavily crevassed

glaciers fringing the coast were an effectual bar to a march with

sledges.

However, time was pressing, and we were fortunate to get winter

quarters as

near as this to our starting-point for the south.  THE "NIMROD" LYING OFF THE PENGUIN ROOKERY, CAPE ROYDS

|