| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2018 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

| CHAPTER

VII WINTER QUARTERS AT CAPE ROYDS OUTSIDE AND INSIDE The bed question: Acetylene Gas-plant After about

four days' hard work at

the Front Door Bay landing-place, the bulk of the stores was recovered,

and I

think we may say that there was not much lost permanently, though, as

time went

on, and one or two cases that were required did not turn up, we used to

wonder

whether they had been left on board the ship, or lay buried under the

ice. We

do know for certain that our only case of beer lies to this day under

the ice,

and it was not until a few days before our final departure that one of

the

scientists of the expedition dug out some volumes of the Challenger

reports,

which had been intended to provide us with useful reading matter during

the

winter nights. A question often debated during the long, dark days was

which of

these stray sheep, the Challenger reports or the case of beer, any

particular

individual would dig for if the time and opportunity were available. In

moving

up the recovered stores, as soon as a load arrived within fifteen yards

of the

hut, where, at this time of the year, the snow ended, and the bare

earth lay

uncovered, the sledges were unpacked, and one party carried the stuff

up to the

south side of the hut, whilst the sledges returned to the landing-place

for

more. We were now utilising the ponies every day, and they proved of

great

assistance in moving things to and fro. The stores on the top of the

hill at

Derrick Point were fortunately quite clear of snow, so we did not

trouble to

transport them, contenting ourselves with getting down things that were

of

immediate importance. Day by day we continued collecting our scattered

goods,

and within ten days after the departure of the ship we had practically

everything handy to the hut, excepting the coal. The labour had been

both heavy

and fertile in minor accidents. Most of us at one time or another had

wounds

and bruises to be attended to by Marshall, who was kept busy part of

every day

dressing the injuries. Adams was severely cut in handling some

iron-bound

cases, and I managed to jamb my fingers in the motor-car. The annoying

feature

about these simple wounds was the length of time it took for them to

heal in

our special circumstances. The irritation seemed to be more pronounced

if any

of the earth got into the wound, so we always took care, after our

first

experiences, to go at once to Marshall for treatment, when the skin was

broken.

The day after the ship left we laid in a supply of fresh meat for the

winter,

killing about a hundred penguins and burying them in a snow-drift close

to the

hut. By February 28 we were practically in a position to feel contented

with

ourselves, and to look further afield and explore the neighbourhood of

our

winter quarters.

DIGGING OUT STORES AFTER THE CASES HAD BEEN BURIED IN DURING A BUZZARD From the door

of our hut, which

faced the north-west, we commanded a splendid view of the sound and the

western

mountains. Right in front of us, at our door, lay a small lake, which

came to

be known as Pony Lake; to the left of that was another sheet of ice

that became

snow-covered in the autumn, and it was here in the dark months that we

exercised the ponies, and also ourselves. Six times up and down the

"Green

Park," as it was generally called, made a mile, and it was here, before

darkness came on, that we played hockey and football. To the left of

Green Park

was a gentle slope leading down between two cliffs to the sea, and

ending in a

little bay known as Dead Horse Bay. On either side of this valley lay

the

penguin rookery, the slopes being covered with guano, and during the

fairly

high temperatures that held sway up to April, the smell from these

deserted

quarters of the penguins was extremely unpleasant. On coming out of the

hut one

had only to go round the corner of the building in order to catch a glimpse of Mount Erebus, which lay directly behind us. Its summit was

about fifteen miles from our winter quarters, but its

slopes and foothills commenced within three-quarters of a 'mile of the

hut. Our

view was cut off in all directions from the east to the south-west by

the ridge

at the head of the valley where the hut stood. On ascending this ridge,

one

looked over the bay to the south-east,. where lay Cape Berne. To the

right was

Flagstaff Point, and to the left lay, at the head of the Bay, the

slopes of

Erebus. There were many localities which became favourite places for

walks, and

these are shown on the Plan. Sandy Beach, about a mile away to the

north-west

of the hut, was generally the goal of any one taking exercise, when the

uncertainty of the weather warned us against venturing further afield,

and

while-the dwindling light still permitted us to go so far. It was here

that we

sometimes exercised the ponies, and they much enjoyed rolling in the

soft sand.

The beach was formed of black volcanic sand, blown from the surrounding

hills,

and later on the pressed-up ice, which had been driven ashore by the

southward

movement of the pack, also became covered with the wind-borne dust and

sand.

The coast-line from Flagstaff Point right round to Horse Shoe Bay, on

the north

side of Cape Royds, was jagged and broken up. At some points

ice-cliffs, in

others. bare rocks, jutted out into the sea, and here and there small

beaches

composed of volcanic sand were interposed. Our local scenery, though

not on a

grand scale, loomed large in the light of the moon as the winter nights

lengthened. Fantastic shadows made the heights appear greater and the

valleys

deeper, casting a spell of unreality around the place, which never

seemed to

touch it by day. The greatest height of any of the numerous

sharp-pointed spurs

of volcanic rock was not more than three hundred feet, but we were

infinitely

better off as regards the interest and the scenery of our winter

quarters than

the expedition which wintered in McMurdo Sound between 1901 and 1904.

Our walks

amongst the hills and across the frozen lakes were a great source of

health and

enjoyment, and as a field of work for geologists and biologists, Cape

Royds far

surpassed Hut Point. The largest lake, which lay about half a mile to

the

north-east, was named Blue Lake, from the intensely vivid blue of the

ice. This

lake was peculiarly interesting to Mawson, who made the study of ice

part of

his work. Beyond Blue Lake, to the northward, lay Clear Lake, the

deepest

inland body of water in our vicinity. To the left as one looked north,

close to

the coast, was a circular basin which we called Coast Lake, where, when

we

first arrived, hundreds of skua gulls were bathing and flying about.

Following

the coast from this point back towards winter quarters was another body

of

water called Green Lake. In all these various lakes something of

interest to

science was discovered, and though they were quite small, they were

very

important to our work and in our eyes, and were a source of continuous

interest

to us during our stay in the vicinity. Beyond Blue Lake, to the east,

rose the

lower slopes of Mount Erebus, covered with ice and snow. After passing

one or

two ridges of volcanic rocks, there stretched a long snow plain, across

which

sledges could travel without having their runners torn by gravel. The

slope

down to Blue Lake was picked out for ski-ing, and it was here, in the

early

days, when work was over, that some of our party used to slide from the

top of

the slope for about two hundred feet, arriving at the bottom in a few

seconds,

and shooting out across the frozen surface of the Lake, until brought

up by the

rising slope on the other side. To the north of Clear Lake the usual

hills of

volcanic rock separated by valleys filled more or less with

snow-drifts,

stretched for a distance of about a mile. Beyond this lay the coast, to

the

right of which, looking north, was Horse Shoe Bay, about four miles

from our

winter quarters; further to the right of the northern end of Cape Royds

the

slopes of Erebus were reached again. From the northern coast a good

view could

be obtained of Cape Bird, and from the height we could see Castle Rock

to the

south, distant about eighteen miles from the winter quarters. The walk

from Hut

Point to Castle Rock was familiar to us on the last expedition. It

seemed much

nearer than it really was, for in the Antarctic the distances are most

deceptive, curiously different effects being produced by the variations

of

light and the distortion of mirage. As time went on

we felt more arid

more satisfied with our location, for there was work of interest for

every one.

The Professor and Priestley saw open before them a new chapter of

geological

history of great interest, for Cape Royds was a happier hunting-ground

for the

geologist than was Hut Point. Hundreds of erratic boulders lay

scattered on the

slopes of the adjacent hills, and from these the geologists hoped to

learn

something of the past conditions of Ross Island. For Murray, the lakes

were a

fruitful field for new research. The gradually deepening bay was full

of marine

animal life, the species varying with the depth, and here also an

inexhaustible

treasure-ground stretched before the biologist. Adams, the

meteorologist, could

not complain, for Mount Erebus was in full view of the meteorological

station,

and this fortunate proximity to Erebus and its smoke-cloud led, in a

large

measure, to important results in this branch. For the physicist the

structure

of the ice, varying on various lakes, the different salts in the earth,

and the

magnetic conditions of the rocks claimed investigation, though, indeed,

the

magnetic nature of the rocks proved a disadvantage in carrying out

magnetic

observations, for the delicate instruments were often affected by the

local

attraction. From every point of view I must say that we were extremely

fortunate in the winter quarters to which we had been led by the state

of the

sea ice, for no other spot could have afforded more scope for work and

exercise. Before we had

been ten days ashore

the hut was practically completed, though it was over a month before it

had

been worked up from the state of an empty shell to attain the fully

furnished

appearance it assumed after every one had settled down and arranged his

belongings. It was not a very spacious dwelling for the accommodation

of

fifteen persons, but our narrow quarters were warmer than if the hut

had been

larger. The coldest part of the house when we first lived in it was

undoubtedly

the floor, which was formed of inch tongue-and-groove boarding, but was

not

double-lined. There was a space of about four feet under the hut at the

north-west end, the other end resting practically on the ground, and it

was

obvious to us that as long as this space remained we would suffer from

the

cold, so we decided to make an airlock of the area under the hut. To

this end

we decided to build a wall round the south-east and southerly sides,

which were

to windward, with the bulk of the provision cases. To make certain that

no air

would penetrate from these sides we built the first two or three tiers

of cases

a little distance out from the walls of the hut, pouring in volcanic

earth

until no gaps could be seen, and the earth was level with the cases;

then the

rest of the stores were piled up to a height of six or seven feet. This

accounted for one side and one end. On either side of the porch two

other

buildings were gradually erected. One, built out of biscuit cases, the

roof

covered with felt and canvas, was a store-room for Wild, who looked

after the

issue of all foodstuffs. The building on the other aide of the porch

was a much

more ambitious affair, and was built by Mawson, to serve as a chemical

and

physical laboratory. It was destined, however, to be used solely as a

store-room, for the temperature within its walls was practically the

same as

that of the outside air, and the warm, moist atmosphere rushing out

from the

hut covered everything inside this store-room with fantastic ice

crystals. The lee side of

the hut ultimately

became the wall of the stables, for we decided to keep the ponies

sheltered

during the winter. During the blizzard we experienced on February 18,

and for

the three following days, the animals suffered somewhat, mainly owing

to the

knocking about they had received whilst on the way south in the ship.

We found

that a shelter, not necessarily warmed to a high temperature, would

keep the

ponies in better condition than if they were allowed to stand in the

open, and

by February 9 the stable building was complete. A double row of cases

of maize,

built at one end to a height of five feet eight inches, made one end,

and then

the longer side of the shelter was composed of bales of fodder. A wide

plank at

the other end was cemented into the ground, and a doorway left. Over

all this

was stretched the canvas tarpauling which we had previously used in the

fodder

hut, and with planks and battens on both sides to make it wind-proof,

the

stable was complete. A wire rope was stretched from one end to the

other on the

side nearest to the hut, and the ponies' head-ropes were made fast to

this. The

first night that they were placed in the stable there was little rest

for any

of us, and during the night some of the animals broke loose and

returned to

their valley. Shortly afterwards Grisi, one of the most high-spirited

of the

lot, pushed his head through a window, so the lower halves of the hut

windows

bad to be boarded up. The first strong breeze we had shook the roof of

the

stable so much that we expected every moment it would blow away, so

after the

gale all the sledges except those which were in use were laid on the

top of the

stable, and a stout rope passed from one end to the other. The next

snowfall

covered the sledges and made a splendid roof, upon which no subsequent

wind had

any effect. Later, another addition was made to the dwellings outside

the hut

in the shape of a series of dog-houses for those animals about to pup,

and as

that was not an uncommon thing down there, the houses were constantly

occupied. On the

south-east side of the hut a

store-room was built, constructed entirely of cases, and roofed with

hammocks

sewn together. Here we kept the tool-chest, shoe-makers' outfit, which

was in

constant requisition, and any general stores that had to be issued at

stated

times. The first heavy blizzard found this place out, and after the

roof had

been blown off, the wall fell down, and we had to organise a party,

when the

weather got fine, to search for anything that might be lost, such as

mufflers,

woollen helmets, and so on. Some things were blown more than a mile

away. I

found a Russian felt boot, weighing five pounds, lying three-quarters

of a mile

from the crate in which it had been stowed, and it must have had a

clear run in

the air for the whole of this distance, for there was not a scratch on

the

leather; if it had been blown along the rocks, which lay in the way,

the

leather would certainly have been scratched all over. The chimney,

which was an

iron pipe, projecting two or three feet above the roof of the hut, and

capped

by a cowl, was let through the rocf at the south-east end, and secured

by

numerous rope stays supporting it at every point from which the wind

could

blow. We were quite

free from the trouble

of down draughts or choking with snow, such as had been of common

occurrence in

the large hut on the Discovery

expedition. Certainly the revolving cowl blew off during the first

blizzard,

and this happened again in the second, so we took the hint and left it

off for

good, without detriment, as it happened, to the efficiency of the

stove. The dog kennels

were placed close to

the porch of the hut, but only three of the dogs were kept. constantly

chained

up. The meteorological station was on the weather side of the hut on

the top of

a small ridge, about, twenty feet above the hut and forty feet above

sea-level,

and a natural path led to it. Adams laid it out, and the regular

readings of

the instruments began on March 22. The foundation of the thermometer

screen consisted

of a heavy wooden case resting on rocks. The case was three-quarters

filled

with rock, and round the outside were piled more blocks of kenyte; the

crevices

between them were filled with volcanic earth on to which water was

poured, the

result being a structure as rigid its the ground itself. On each side

of the

box a heavy upright was secured by the rocks inside the case and by

bolts at

the sides, and to these uprights the actual meteorological screen, one

of the

Stevenson pattern and of standard size, was bolted. As readings of the

instruments were to be taken day and night at intervals of two hours,

and as it

was quite possible that the weather might be so thick that a person

might be

lost in making his way between the screen and the hut, a line was

rigged up on

posts, which were cemented into the ground by ice, so that in the

thickest

weather the observer could be sure of finding his way by following this

very

substantial clue. The inside of

the hut was not long

in being fully furnished, and a, great change it was from the bare

shell of our

first days of occupancy. The first thing done was to peg out a space

for each

individual, and we saw that the best plan would be to have the space

allotted

in sections, allowing two persons to share one cubicle. This space for

two men

amounted to six feet six inches in length and seven feet in depth from

the wall

of the hut towards the centre. There were seven of these cubicles, and

a space

for the leader of the expedition; thus providing for the fifteen who

made up

the shore-party. The accompanying photographs will give an idea of the

hut as

finished. One of the most important parts of the interior construction

was the

dark-room for the photographers. We were very short of wood, so cases

of

bottled fruit, which had to be kept inside the hut to prevent them

freezing,

were utilised for building the walls. The dark-room was constructed in

the

left-hand corner of the hut as one entered, and the fruit-cases were

turned

with their lids facing out, so that the contents could be removed

without

demolishing the walls of the building. These cases, as they were

emptied, were

turned into lockers, where we stowed our spare gear and so obtained

more room

in the little cubicles. The interior of the dark-room was fitted up by

Mawson

and the Professor. The sides and roof were lined with the felt left

over after

the hut was completed. Mawson made the fittings complete in every

detail, with

shelves, tanks, &c., and the result was as good as any one

could desire in

the circumstances.  ICE FLOWERS ON NEWLY-FORMED SEA ICE EARLY A long ridge of

rope wire was

stretched from one end of the hut to the other on each side, seven feet

out

from the wall; then at intervals of six feet another wire was brought

out from

the wall of the hut, and made fast to the fore and aft wire. These

lines marked

the boundaries of the cubicles, and sheets of duck sewn together hung

from

them, making a good division. Blankets were served out to hang in the

front of

the cubicle, in case the inhabitants wanted at any time to "sport their

oak." As each of the cubicles had distinctive features in the

furnishing

and general design, especially as regards beds, it is worth while to

describe

them fully. This is not so trivial a matter as it may appear to some

readers,

for during the winter months the inside of the hut was the whole

inhabited

world to us. The wall of Adams and Marshall's cubicle, which was next

to my

room, was fitted with shelves made out of Venesta cases, and there was

so much

neatness and order about this apartment that it was known by the

address,

"No. 1 Park Lane." In front of the shelves hung little gauze

curtains, tied up with blue ribbon, and the literary tastes of the

occupants

could be seen at a glance from the bookshelves. In Adams' quarter the

period of

the French Revolution and the Napoleonic era filled most of his

bookshelves,

though a complete edition of Dickens came in a good second. Marshall's

shelves

were stocked with bottles of medicine, medical works, and some general

literature. The dividing curtain of duck was adorned by Marston with

life-sized

coloured drawings of Napoleon and Joan of Aro. Adams and Marshall did

Sandow

exercises daily, and their example was followed by other men later on,

when the

darkness and bad weather made open-air work difficult. The beds of this

particular cubicle were the most comfortable in the hut, but took a

little

longer to rig up at night than most of the others. This disadvantage

was more

than compensated for by the free space gained during the day, and by

permission

of the owners it was used as consulting-room, dispensary, and operating

theatre. The beds consisted of bamboos lashed together for extra

strength, to

which strips of canvas were attached, so that each bed looked like a

stretcher.

The wall end rested on stout cleats screwed on to the side of the hut,

the

other ends on chairs, and so supported, the occupants slept soundly and

comfortably. The next

cubicle on the same side

was occupied by Marston and Day, and as the former was the artist and

the

latter the general handy man of the expedition, one naturally found an

ambitious scheme of decoration. The shelves were provided with beading,

and the

Venesta boxes were stained brown. This idea was copied from "No. 1 Park

Lane," where they had stained all their walls with Condy's Fluid.

Marston

and Day's cubicle was known as "The Gables," presumably from the

gabled appearance of the shelves. Solid wooden beds, made out of old

packing-cases and upholstered with wood shavings covered witE blankets,

made

very comfortable couches, one of which could be pushed during meal

times out of

the way of the chairs. The artist's curtain was painted to represent a

fireplace and mantelpiece in civilisation; a cheerful fire burned in

the grate,

and a bunch of flowers stood on the mantelpiece. The dividing curtain

between

it and No. 1 Park Lane, on the other side of the cubicle, did not

require to be

decorated, for the colour of Joan of Aro, and also portions of

Napoleon, had

oozed through the canvas. In "The Gables" was set up the lithographic

press, which was used for producing pictures for the book which was

printed at

our winter quarters. The next

cubicle on the same side

belonged to Armytage and Brocklehurst. Here everything in the way of

shelves and

fittings was very primitive. I lived in Brocklehurst's portion of the

cubicle

for two months, as he was laid up in my room, and before I left it I

constructed a bed of empty petrol cases. The smell from these for the

first

couple of nights after rigging them up was decidedly unpleasant, but it

disappeared after a while. Next to Brocklehurst's and Armytage's

quarters came

the pantry. The division between the cubicle and the pantry consisted

of a tier

of cases, making a substantial wall between the food and the heads of

the

sleepers. The pantry, bakery, and store-room, all combined, measured

six feet

by three, not very spacious, certainly, but sufficient

to work in. The far end of the hut

constituted the other wall of the pantry, and was lined with shelves up

to the

slope of the roof. These shelves were continued along the wall behind

the

stove, which stood about four feet out from the end of the house, and

an

erection of wooden battens and burlap or sacking concealed the

biological

laboratory. The space taken up by this important department was four

feet by

four, but lack of ground area was made up for by the shelves, which

oontained

dozens of bottles soon to be filled with Murray's biological captures. Beyond the

stove, facing the pantry,

was Mackay and Roberts' cubicle, the main feature of which was a

ponderous

shelf, on which rested mostly socks and other light articles, the only

thing of

weight being our gramophone and records. The bunks were somewhat feeble

imitations of those belonging to No. 1 Park Lane, and the troubles that

the

owners went through before finally getting them into working order

afforded the

rest of the community a good deal of amusement. I can see before me now

the

triumphant face of Mackay, as he called all hands round to see his

design. The

inhabitants of No. 1 Park Lane pointed out that the bamboo was not a

rigid

piece of wood, and that when Mackay's weight came on it the middle

would bend

and the ends would jump off the supports unless secured. Mackay

undressed

before a critical audience, and he got into his bag and expatiated on

the

comfort and luxury he was experiencing, so different to the hard boards

he had

been lying on for months. Roberts was anxious to try his couch, which

was

constructed on the same principle, and the audience were turning away

disappointed at not witnessing a catastrophe, when suddenly a crash was

heard,

followed by a strong expletive. Mackay's bed was half on the ground,

one end of

it resting at a most uncomfortable angle. Laughter and pointed remarks

as to

his capacity for making a bed were nothing to him; he tried three times

that

night to fix it up, but at last had to give it up for a bad job. In due

time he

arranged fastenings, and after that he slept in comfort. Between this

cubicle and the next

there was no division, neither party troubling about the matter. The

result was

that the four men were constantly at war regarding alleged

encroachments on

their ground. Priestley, who was long-suffering, and who occupied the

cubicle

with Murray, said he did not mind a chair or a volume of the

"Encyclopaedia Britannica" being occasionally deposited on him while

he was asleep, but that he thought it was a little too strong to drop

wet

boots, newly arrived from the stables, on top of his belongings.

Priestley and Murray

had no floor-space at all in their cubicle, as their beds were built of

empty

dog-biscuit boxes. A division of boxes separated the two

sleeping-places, and

the whole cubicle was garnished on Priestley's side with bits of rock,

ice-axes, hammers and chisels, and on Murray's with biological

requisites. Next came one

of the first cubicles

that had been built. Joyce and Wild occupied the "Rogues' Retreat," a

painting of two very tough characters drinking beer out of pint mugs,

with the

inscription The Rogue's Retreat painted underneath, adorning the

entrance to

the den. The couches in this house were the first to be built, and

those of the

opposite dwelling, The Gables, were copied from their design. The first

bed had

been built in Wild's store-room for secrecy's sake; it was to burst

upon the

view of every one, and to create mingled feelings of admiration and

envy,

admiration for the splendid design, envy of the unparalleled luxury

provided by

it. However, in building it, the designer forgot the size of the

doorway he had

to take it through, and it had ignominiously to be sawn in half before

it could

be passed out of the store-room into the hut. The printing press and

type case

for the polar paper occupied one corner of this cubicle. The next and

last compartment was

the dwelling-place of the Professor and Mawson. It would be difficult

to do

justice to the picturesque confusion of this compartment; one hardly

likes to

call it untidy, for the things that covered the bunks by daytime could

be

placed nowhere else conveniently. A miscellaneous assortment *of

cameras,

spectroscopes, thermometers, microscopes, electrometers, and the like

lay in

profusion on the blankets. Mawson's bed consisted of his two boxes, in

which he

had stowed his scientific apparatus on the way down, and the

Professor's bed

was made out of kerosene cases. Everything in the way of tin cans or

plug-topped, with straw wrappers belonging to the fruit bottles, was

collected

by these two scientific men. Mawson, as a rule, put his possessions in

his

store-room outside, but the Professor, not having any retreat like

that, made a

pile of glittering tins and coloured wrappers at one end of his bunk,

and the

heap looked like the nest of the Australian bower bird. The straw and

the tins

were generally cleared away when the Professor and Priestley went in

for a

day's packing of geological specimens; the straw wrappers were utilised

for

wrapping round the rocks and the tins were filled with paper wrapped

round the

more delicate geological specimens. The name given, though not by the

owners,

to this cubicle was "The Pawn Shop," for not only was there always a

heterogeneous mass of things on the bunks, but the wall of the

dark-room and

the wall of the hut at this spot could not be seen for the multitude of

eases

ranged as shelves and filled with a varied assortment of note-books and

instruments. In order to

give as much free space

as possible in the centre of the hut we had the table so arranged that

it could

be hoisted up over our heads after meals were over. This gave ample

room or the

various carpentering and engineering efforts that were constantly going

on.

Murray built the table out of the lids of packing-cases, and though

often

scrubbed, the stencilling on the cases never came out. We had no

table-cloth,

but this was an advantage, for a well-scrubbed table had a cleaner

appearance

than would be obtained with such washing as could be done in an

Antarctic

laundry. The legs of the table were detachable, being after the fashion

of

trestles, and the whole affair, when meals were over, was slung by a

rope at

each end about eight feet from the floor. At first we used to put the

boxes

containing knives, forks, plates, and bowls on top of the table before

hauling

it up, but after these had fallen on the unfortunate head of the person

trying

to get them down, we were content to keep them on the floor. I had been very

anxious as regards

the stove, the most important part of the hut equipment, when I heard

that,

after the blizzard that kept me on board the Nimrod,

the temperature of the hut was below zero, and that socks

put to dry in the baking-ovens came out as damp as ever the following

morning.

My anxiety was dispelled after the stove had been taken to pieces

again, for it

was found that eight important pieces of its structure had not been put

in. As

soon as this omission was rectified the stove acted splendidly, and the

makers

deserve our thanks for the particular apparatus they picked out as

suitable for

us. The stove was put to a severe test, for it was kept going day and

night for

over nine months without once being out for more than ten minutes, when

occasion required it to be cleaned. It supplied us with sufficient heat

to keep

the temperature of the hut sixty to seventy degrees above the outside

air. Enough

bread could be baked to satisfy our whole hungry party of fifteen every

day;

three hot meals a day were also cooked, and water melted from ice at a

temperature of perhaps twenty degrees below zero in sufficient quantity

to

afford as much as we required for ourselves, and to water the ponies

twice a

day, and all this work was done on a consumption not exceeding five

hundredweight of coal per week. After testing the stove by running it

on an

accurately measured amount of coal for a month, we were reassured about

our

coal-supply being sufficient to carry us through the winter right on to

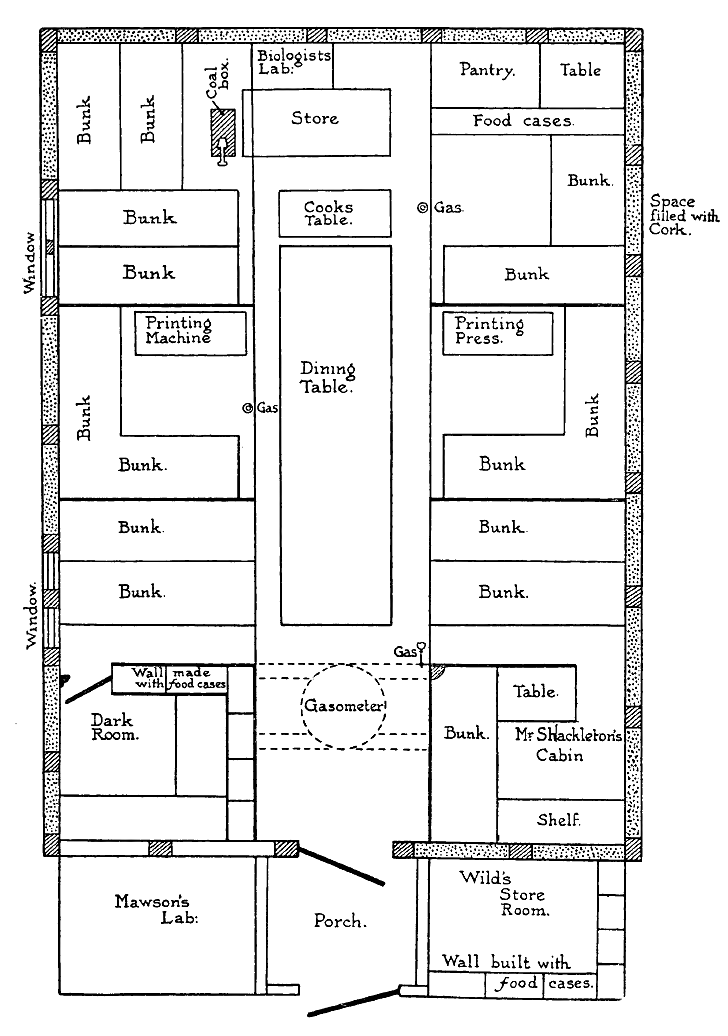

sledging time.  MARSTON IN HIS BED  Plan ot the Hut at Winter Quarters |