| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2018 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

| APPENDIX I SOME NOTES BY JAMES MURRAY, BIOLOGIST TO THE EXPEDITION PENGUINS THOUGH so much

has been written

about them, the penguins always excite fresh interest in every one who

sees

them for the first time. There is endless interest in watching them,

the

dignified Emperor, dignified notwithstanding his clumsy waddle, going

along

with his wife (or wives) by his side, the very picture of a successful,

self-satisfied happy, unsuspicious countryman, gravely bowing like a

Chinaman

before a yelping dog and the little undignified matter-of-fact Adelie,

minding

his own business in a way worthy of emulation. They are perfectly

adapted to a

narrow round of life, and when compelled to face matters outside of

their

experience they often behave with apparent stupidity, but sometimes

show a good

deal of intelligence. Their

resemblance to human beings is

always noticed. This is partly due to the habit of walking erect, but

there are

truly a great many human traits about them. They are the civilised

nations of

these regions, and their civilisation, if much simpler than ours, is in

some

respects higher and more worthy of the name. But there is a good deal

of human

nature in them too. As in the human race, their gathering in colonies

does not

show any true social instinct. They are merely gregarious; each penguin

is in

the rookery for his own ends, there is no thought of the general good.

You

might exterminate an Adelie rookery with the exception of one bird, and

he

would be in no way concerned so long as you left him alone. Some little

suggestion of altruism

will appear in dealing, with the nesting habits of the Adelie. Thieving

is

known, among the Adelies at least. One very pleasing trait is shown,

which they

have in common with man. Eating is not with them the prime business in

life, as

it is with the common fowl and most animals. Both Emperors and Addles,

when the

serious business of nesting is off their minds, show a legitimate

curiosity.

Having fed and got into good condition they leave the sea and go off in

parties, apparently to see the country, and travel for days and weeks. THE

EMPEROR. We saw the

Emperor only as a summer

visitor. Having finished nesting, fed up and become glossy and

beautiful, they

came up out of the sea in large or small parties, apparently to have a

good

time before moulting. While the Adelies were nesting they began to come

in

numbers to inspect the camp. Passing among the Adelies, the two kinds

usually

paid no attention to one another, but sometimes an Adele would think an

Emperor

came too close to her nest, and a curious unequal quarrel would ensue,

the

little impudence pecking and scolding, and the Emperor scolding back,

with some

loss of dignity. Though more than able to hold her own with the tongue,

the

Adele knew the value of discretion whenever the Emperor raised his

flipper. They were

curious about any unusual

object and would come a long way to see a motor-oar or a man. When out

on these

excursions the leader of a party keeps them together by a long shrill

squawk.

Distant parties salute in this way and continue calling till they get

pretty

close. A party could be made to approach by imitating this call. The

first

party to arrive inspected the boat, then crossed the lake to the camp.

Soon

they discovered the dogs, and thereafter all other interests were

swallowed up

in the interest excited by them. After the first discovery crowds came

every

day for a long time, and from the manner in which they went straight to

the

kennels one was tempted to believe that the fame of them had been

noised

abroad. CEREMONIES

OF

MEETING Emperors are

very ceremonious in

meeting other Emperors or men or dogs. They come up to a party of

strangers in

a straggling procession, some big important aldermanic fellow leading.

At a

respectful distance from the man or dog they bah, the old male waddles

close up

and bows gravely till his beak is almost touching his breast. Keeping

his head

bowed he makes a long speech, in a muttering manner, short sounds

following in

groups of four or five. Having finished the speech, the head is still

kept

bowed a few seconds for politeness' sake, then it is raised and he

describes

with his bill as large a circle as the joints of his neck will allow,

looking

in your face at last to see if you have understood. If you have not

comprehended,

as is usually the case, he tries again. He is very patient with your

stupidity,

and feels sure that he will get it into your dull brain if he keeps at

it long

enough. By this time his followers are getting impatient. They are sure

he is

making a mess of it. Another male will waddle forward with dignity,

elbow the

first aside as if to say, "I'll show you how it ought to be done,"

and goes through the whole business again. Their most solemn ceremonies

were

used towards the dogs, and three old fellows have been seen calmly

bowing and

speaking simultaneously to a dog, which for its part was yelping and

straining

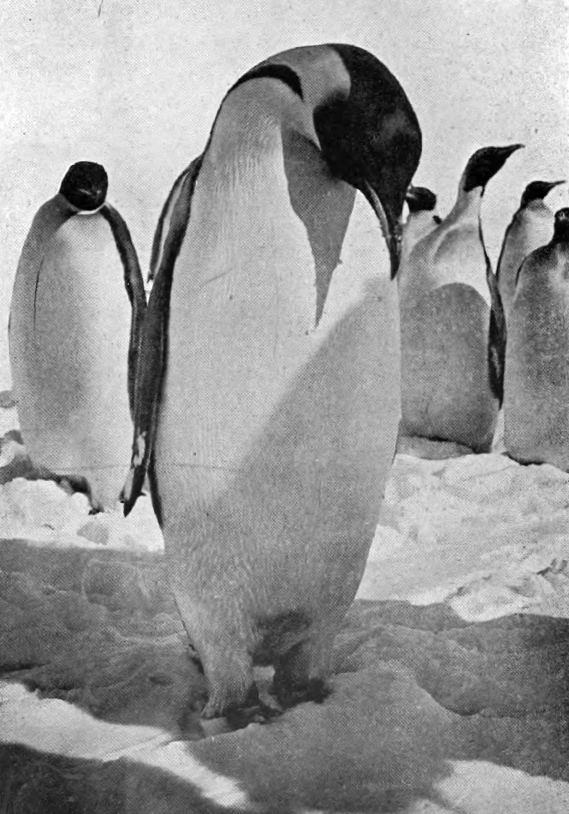

at its chain in the effort to get at them.  EMPEROR PENGUIN They seem to

regard men as penguins

like themselves. They are quite unsuspicious and slow to take alarm, so

long as

you stay still or move very slowly. If you walk too fast among them, or

if you

touch them, they get frightened and run away, only fighting when

closely

pressed. As one slowly retreats, fighting, he has a ludicrous

resemblance to a

small boy being bullied by a big one, his flipper towards the foe

elevated in

defence, and making quick blows at the bully. It is well to keep clear

of that

flipper when he strikes, for it is very powerful, and might break an

arm. Emperors were

killed by the dogs,

but it is likely that the animals hunted in couples to do this. A long

fight

was witnessed between an Emperor and the dog Ambrose, the largest of

our dogs

native to the Antarctic. The penguin was quick enough in movement to

keep

always facing the dog, and the flipper and long sharp bill were

efficient

weapons, as Ambrose seemed to appreciate. Only the bill was used, and

it

appeared to be due to short sight that the blow always fell short. Many

of the apparently

stupid acts of both kinds of penguins are doubtless to be traced to

their very

defective sight in air. The Emperor can

hardly be said to

migrate since he remains to breed during the winter darkness, and

spends the

summer among the ice or on shore in the same region. Yet he travels a

good

deal, and the meaning of some of his journeyings remains-a mystery. The

visits

of touring-parties to the camp have been described. At the same season

(early

summer), when the motor-ear was making frequent journeys southward to

Glacier

Tongue with stores for depot-laying, we crossed on the way a great many

penguin

tracks. Many of these were beaten roads, where large parties had

passed, some

walking, some tobogganning. They all trended roughly to the south-east,

and the

wing-marks and footmarks showed that they were all outward bound from

the open

sea towards the shores of Ross Island. Some of the roads were twelve

miles or

more from the open sea. There were no return tracks. We expected to

find that they had

gone in to seek sheltered moulting-places, but on a motor trip to the

Turk's

Head we skirted a long stretch of the coast and found no Emperors. On journeys

they often travel many

miles walking erect, when they get along at a very slow shuffle, making

only a

few inches at each step. In walking thus they keep their balance by the

assistance of the tail, which forms a tripod with the legs. When on a

suitable

snow surface they progress rapidly by tobogganning, a very graceful

motion,

when they make sledges of their breasts and propel themselves by the

powerful

legs, balancing and perhaps improving their speed by means of the

wings. Eight of them

visited the motor-car

one day, near Tent Island, sledging swiftly towards us. Two of them

were very

determined fighters and refused to be driven away. One obstinate

phlegmatic old

fellow, who wasn't going to be hurried by anybody, did learn to hustle

as the

car bore down upon him. THE

ADELIE The Adelie is

always comical. He

pops out of the water with startling suddenness, like a

jack-in-the-box,

alights on his feet, gives his tail a shake, and. toddles off about his

business. He always knows where he wants to go, and what he wants to

do, and isn't

easily turned aside from his purpose. In the water

the Adelie penguins

move rapidly and circle in the same way as a porpoise or a dolphin, for

which

they are easily mistaken at a little distance. On level ice or snow

they can

run pretty fast, getting along about as fast as a man at a smart walk.

They

find even a small crack a serious obstruction, and pause and measure

with the

eye one of a few inches before very cautiously hopping it. They flop

down and

toboggan over any opening more than a few inches wide. They can climb

hills of

a very stoop angle, but on uneven ground they use their flippers as

balancers.

They toboggan with great speed on snow or ice, or even on the bare

rocks when

scared, but in that case their flippers are soon bleeding. Very rarely

they

swim in the water like ducks. They lie much lower in the water than the

duck.

The neck is below the surface and the head is just showing. The Adelie is

very brave in the

breeding-season. His is true courage, not the courage of ignorance, for

after

he has learned to know man, and fear him, he remains to defend the nest

against

any odds. When walking among the nests one is assailed on all sides by

powerful

bills. Most of the birds sit still on the nests, but the more

pugnacious ones

run at you from a distance and often take you unawares. We wore for

protection

long felt boots reaching well above the knee. Some of the clever ones

knew that

they were wasting their efforts on the felt boots, and would come up

behind,

hop up and seize the skin above the boot, and hang on. tight, beating

with

their wings. One of these little furies, hanging to your flesh and

flapping his

strong flippers so fast that you can hardly see them move, is no joke.

A man

once stumbled and fell into a colony of Adelies, and before he could

recover

himself and scramble out they were upon him, and he bore the marks of

their

fury for some time. Some birds

became greatly interested

in the camp, and wanted to nest there. One bird (we believe it was

always the

same one) couldn't be kept away, and came daily, sometimes bringing

some

friends. As he passed among the dogs, which were barking and trying to

get at

him, he stood and defied them all, and when we turned out to try to

drive him

away, he offered to take us all on too, and was finally saved against

his will,

and carried away by Brocklehurst, a wildly struggling, unconquerable

being. The old birds

enjoy play, while the

young ones have no leisure for play, being engrossed in satisfying the

enormous

appetites they have when growing. Four or five Adelies were playing on

the

ice-floe. One acted as leader, advanced to the edge of the floe, waited

for the

others to line up, raised his flipper, when they all dived in. In a few

seconds

they all popped out again, and repeated the performance, always

apparently

directed by the one. And so they went on for hours. While the Nimrod was frozen in the pack, some

dozens of them were disporting themselves in a sea-pool alongside. They

swam

together in the duck fashion, then at a squawk from one they all dived

and came

up at the other side of the pool.  AN ADELIE CALLING FOR A MATE AFTER COMMENCING THE NEST When the

rookery is pretty well

filled, and the nest-building is in full swing, the birds have a busy

and

anxious time. To get enough of suitable small stones is a matter of

difficulty,

and may involve long journeys for each single stone. The temptation is

too

strong for some of them, and they become habitual thieves. The majority

remain

stupidly honest. Amusing complications result. The bearing of the thief

clearly

shows that he knows he is doing wrong. He has a conscience, at least a

human

conscience, i.e. the fear of being found out. Very different is the

furtive

look of the thief, long after he is out of danger of pursuit, from the

expression of the honest penguin coming home with a hard-earned stone. An honest one

was bringing stones

from a long distance. Each stone was removed by a thief as soon as the

owner's

back was turned. The honest one looked greatly troubled as he found

that his

heap didn't grow, but he seemed incapable of suspecting the cause. A thief,

sitting on its own nest,

was stealing from an adjacent nest, whose honest owner was also at

home, but

looking unsuspectingly in another direction. Casually he turned his

head and

caught the thief in the act. The thief dropped the stone and pretended

to be

busy picking up an infinitesimal crumb from the neutral ground. The

stone-gathering is a very strong

part of the nesting instinct. It was kept up while sitting on the eggs,

and if

at a late stage they lost their eggs or young, they reverted to the

heaping of

stones, which they did in a half-hearted way. Unmated birds occupied

the fringe

of the rookery, and amused themselves piling and stealing till the

chicks began

to hatch out. After the two

eggs were laid the

males appeared to do most of the work. At any hour the males

predominated, a

very few pairs were at the nests, and relieving guard was rarely

noticed. The

females were never seen in the majority. Those which had been recently

down to

feed could be recognised by the fresh crustacea round the nests.

Judging by

this sign, it would seem that some birds never leave the nest to feed

during

the whole period of incubation. Many birds lost their mates through the

occasional breaking loose of a dog. These birds couldn't leave the

nests. REARING

THE

CHICKS The rookery is

most interesting

after the chicks arrive. Many curious things happen as they grow. The

young

chicks are silvery or slaty grey, with darker heads, which are for the

first

day or so heavy and hang down helplessly. As soon as they are hatched

the

mothers take equal share in tending them, whatever they may have been

doing

before that. For some weeks the nest cannot be left untended or the

chicks

would perish of cold or fall victims to the skuas. The parents keep

regular

watches, going down in turn to feed, and relieving guard is an

interesting

ceremony. The bird just arrived from the sea hurries to the nest. It is

anxious

to see the chick, and to feed it; the other is unwilling to resign, but

at last

reluctantly gets off the nest, evidently very stiff, stretches itself,

and

hangs about for a while before going down to the sea. When the young

ones can hold up

their heads the feeding begins. At first the parent tries to induce its

offspring to feed by tickling its bill and throat. The old bird opens

its mouth

and the chick puts its head right in and .picks the food out of the

throat. The

bird can be seen bringing it up into the throat by an effort. If the

young is

unwilling to feed some food is thrown right up on to the ground and a

little of

it picked up again and placed on the chick's bill. After learning the

way there

is no need for such inducement, and the parents are taxed to satisfy

the

clamouring for more. For some weeks

after the young are

hatched life in the rookery goes smoothly along. One parent is always

on the

nest and the young birds do not wander. Then the trouble begins. The

young

begin to move about and if anything disturbs the colony they run about

in

panic. As they don't know nest or parent they cannot return home. They

meet the

case by adopting parents, and run under any bird they come to. The old

birds

resent this and a chick is often pecked away from nest after nest till

exhausted. The skuas get some at this time, but it is surprising how

few. Most

of the chicks take some old one unawares and get in the nest. She may

have a

chick already, or chicks, but as she doesn't know which is her own she

cannot

drive the intruder away. A sorely puzzled bird may be seen trying to

cover four

gigantic chicks. Some of the less precocious youngsters stay at home

long

enough to get to know the nest, and can find their way home after

wandering a

few yards. Such homes keep together a little longer. The time comes

when both parents

must be absent together to get enough food for the growing chicks. Then

the

social order of the rookery breaks down and chaos begins. The social

condition

which is evolved out of the chaos is one of the most remarkable in

nature, yet

it serves its purpose and saves the race. A kind of communism is

established,

but the old birds have no part in it. They cherish the fiction that

they have

nests and children, and when they come up from the sea after feeding it

is

their intention to find the nest and feed their own young only. The

young ones,

for their part, establish a community of parents, and yet it isn't

exactly that

either, though it works out as if it were. It is each bird for itself.

The

chick assumes the first old one that comes within its reach to be its

parent.

Perhaps it really thinks so, as they are all alike.  ADELIE TRYING TO MOTHER A COUPLE OF WELL-GROWN STRANGERS An

old bird,

coming up full of

shrimps, is met by clamorous youngsters before it has time to begin the

search

for its hypothetical home. They order it to stand and deliver. It

objects and

scolds, and runs off. It may be by the irony of fate that it is its own

young

which accost it, but it can't know that. The chickens are both

imperative and

wheedling. Then begins one of those parent hunts which were so familiar

at the

end of the season. The end is never in doubt from the first. Every now

and

again the old one stops and expostulates. This shows weakness. There is

no

indecision on the part of the young one. It never seems anxious as to

the

result, but in the most matter-of-fact and persistent manner hunts the

old one

down. The hunts are often long and exhausting. One chase was witnessed

at Pony

Lake beside the camp. Nine times they circled the lake, and the hunt

was not

over when the watcher had to leave. On that occasion they must have

travelled

miles. At the end the old one stops, and still spluttering and

protesting,

delivers up. One would think that in these circumstances the weaker

chicks

would go to the wall, but it does not appear to be so. There are no

ill-nourished young ones to be seen. Perhaps the hunts take so long

that all

get a chance. A few days

after the eggs began to

hatch there was a severe blizzard, which lasted several days. Snow was

banked

up round most of the birds. A snowdrift crossed the densest part of the

rookery, partly burying many birds. In the deepest part nests and birds

were

covered out of sight, and the only indication of the whereabouts of a

bird was

a little funnel in the snow, at the bottom of which an anxious eye

could be

seen. Many less deeply buried birds had freed one wing or both, which

became

stiff with cold, as they could not be got back again. The snow, melting

by the

heat of their bodies, and refreezing, made walls of ice round the

birds. Many

got alarmed and left the nests, when the snow fell in and buried them.

In the

warm sunny weather that followed the melting snow filled many nests

with pools

of water. Some birds showed ingenuity in dealing with these floods.

They moved

their nests, stone by stone (always keeping a hollow for the eggs or

chicks),

as much as their own width till they reached dry ground. While the

snowdrift

remained some birds whose nests were buried scraped hollows in the snow

and

collected a few stones. On a moderate estimate about half the young

perished in

this blizzard. The old Addles

do not mind the cold.

Their thick blubber and dense fur sufficiently Rrotect them. In a

blizzard they

a will lie still and let the snow cover them. Going to the rookery once

after a

blizzard I could see no penguins; they had entirely disappeared.

Suddenly at some

movement or noise I was surrounded by them; they had sprung up out of

the snow. DOMESTIC

ENTANGLEMENTS While the Adele

appears to be

entirely moral in his domestic arrangements, his stupidity (or his

short-sightedness, which causes him to seem stupid) gives rise to many

domestic

complications. No doubt the presence of our camp upset the social

economy, and

probably when undisturbed nothing of the kind would occur. He has

little sense

of locality, and one little heap of stones is very like another, yet

pairs seem

to have no means of recognising one another but by the rendezvous of

the nest.

Husbands and wives, parents and children, do not know one another, but

if found

at the nest are accepted as bond fide. All the birds

go to their nests

without hesitation when they Dome from the sea by the familiar route,

but if

taken from their nests to some other part of the rookery some find

their way

back without difficulty, others are quite lost. They are most puzzled

when

moved only a little away from home, and they will fight to keep another

bird's

nest while their own is only a couple of feet away. A bird will defend

an egg

or chick in the nest, but if it is removed just outside it will peck at

it and

destroy it. Considering

these facts it will be

evident that if the rookery be disturbed confusion follows. A mere walk

among

the nests caused innumerable entanglements. One bird would leave the

nest in

fright, flop down a yard away beside a nest already occupied, or on a

nest left

exposed by another scared bird. Then one-sided fights would begin, one

bird

attacking another under the impression that it had usurped its nest,

the

rightful owner troubling little about the vicious pecking he was

receiving,

sitting calmly in conscious rectitude. A fight of this kind has been

watched

for an hour at a time, three neighbouring nests having been disturbed.

One bird

had got into another's nest, a second was trying to establish a claim

to the

occupied nest of a third, and meanwhile the chicks of number one were

neglected

in the cold. A bird which had no family came and covered the chicks,

but looked

conscious of wrongdoing and kept ready to bolt on a second's notice.

All these

birds but the last wanted their own nests and were within a yard of

them

without knowing it. In all such

cases, even when a bird

got established on the wrong nest, there was always an adjustment

afterwards.

When they calmed down they became uneasy, probably observing the

landmarks more

critically, and would even leave a nest with chicks for their own empty

nest. A

chick removed from the nest and put alongside was not recognised, and

the old

bird never seemed to connect the facts of the empty nest and the chick

beside

it. If a chick were taken from the nest under the old bird's very eyes

and held

in front of it, it was always the ohick that was viciously attacked,

not the

aggressor. Some

experiments were tried on them

in order to trace the workings of the penguin mind. If a man stood

between a

bird and its nest so as to prevent it from getting on to it, the bird

would

make many attempts to reach home, rushing furiously at the man. After a

time it

would appear to meditate, and then walk off rather disconsolately, make

a tour

of the oolony to which it belonged, and approach the nest from another

side. It

appeared greatly astonished that the intruder was still there. This

curious

trait was often seen. It is like the ostrich burying its head in the

sand and

imagining it is safe, or like a man refusing to believe his own eyes.

It

appears to think that if it takes a turn round, or comes to its nest

from the

other side, the horrible vision will disappear. A bird was

taken from a nest which

had a chick in it and put down at a little distance. Meantime the chick

was put

in a neighbour's nest. Presently the bird came running up. It started

back on

seeing the empty nest, not in alarm or fear, but exactly as if

thinking,

"I've come to the wrong house!" and trotted off to a distant part of

the rookery. Her reasoning seemed to be this: "There was a chick in my

nest, therefore this empty nest cannot be mine." She couldn't imagine

the

chick leaving the nest, and so never searched for it. It was only a

yard from

the nest all the time. After half an hour's searching in vain for any

place

like home she returned to the nest, and accepted the restored chick as

a matter

of course. A lost chick

was never sought for.

There would be no use; it couldn't be recognised. On account of this

peculiarity we were able to make many readjustments of the family

arrangements.

When the blizzard destroyed so many chicks we distributed the young

from nests

where there were two to nests where there were none. They were usually

adopted

eagerly and the plan was quite successful. When both birds

are at a nest that

is disturbed, or when the mate comes up from feeding to relieve guard,

there is

an interchange of civilities in the form of a loud squawking in unison,

accompanied by a curious movement. The birds' necks are crossed, and at

each

squawk they are changed from side to side, first right then left. The

harsh

complaining clamour which they make was for long mistaken for

quarrelling. A bird

returning from the sea came

to the wrong nest and tried to enter into conversation with the

occupant, who

would have nothing to do with him. She knew her mate had just gone off

for the

day, and wouldn't be such a fool as to come back too early, so she sat

still,

indifferent to the squawking of the other. A look of distress came into

his

face as he failed to get any response, and he was slow to realise that

he had

made a mistake. A small colony

was found with about

two dozen large chicks, unattended by any old birds. They were driven

across

the lake to a larger colony Half-way over a few old birds were

squatted,

enjoying a rest. When the chicks saw them they ran up to them joyfully,

saying:

"Here's pa and ma, hooray!" To their surprise they got the reverse of

a cordial welcome, being driven away with vicious peckings. They were

driven on

to the larger colony and were swallowed up in it. The Adelies are

not demonstrative of

their affections. It is difficult to discover if they have any beyond

the

instinctive affection for the young. The pairing appears to be a purely

business matter, and the mates don't even show any power to recognise

one

another. A penguin was injured by the dogs, but it seemed possible that

it

might recover, so we did not at once put it out of pain. In a couple of

days it

died. Shortly after we noticed a live penguin standing by it. We

removed the

dead bird to a distance, and after a while found the other standing

beside it

as before. It was the general opinion that it was the dead bird's mate

which

had found it out. Such an action is entirely opposed to what we expect

after a

long study of their habits. There are always plenty of dead birds about

a rookery,

and the living go about entirely indifferent to them. It is puzzling in

any

point of view, but it is less difficult to believe that the bird found

its dead

mate than that it took an interest in a dead stranger. ALTRUISM When the young

birds are well grown,

if there is an alarm they flock together, and any old birds present in

the

colony form a wall of defence between the young and the enemy. This

habit has

given rise to the belief that they are somewhat communistic in their

social

order, and that the defence of the colony is a concerted action. It is

not so.

Each bird is defending its own young one only, and will often fight

with

another of the defending birds, or peck at any young one which comes in

its

way. There are real

instances of altruism

or kindness to strangers. Our passage through the rookery frightened

away the

parent of a very young chick. A bird passing at the distance of a few

yards

noticed it and came over to it. He cocked his head on one side and

looked at

it, as if saying: "Hullo! this little beggar's deserted; must do

something

for him." He tickled its bill, as the parents do when coaxing the very

young chicks to feed, but it was too much frightened to feed. After

coaxing it

in this way for some time he turned away and put some food upon the

ground,

and, lifting a little in his bill, he put some on each side of the

chick's

bill. Just then the rightful parent returned and the helper ran off.

This was

not an isolated case, but was observed on several occasions. One incident

seemed to reveal true

social instinct. From a small colony of about two dozen nests all the

eggs but

one were taken in order to find out if the birds would lay again. As it

turned

out they did not. The birds sat on their empty nests for some time,

then they

disappeared. When the time came for the solitary egg to hatch, about a

dozen of

the nests were re-occupied and the birds took their share in defending

the one

chick. DEPARTURE

OF

THE YOUNG When they have

shed most of their

down the young birds congregate at the edge of the sea. They cease from

hunting

the old ones for food, and appear to be waiting for something. When the

right

time comes, which they seem to know perfectly, they dive into the sea,

sometimes in small parties, sometimes singly, disappear for a time, and

may be

seen popping up far out to sea. They dive and come up very awkwardly,

bat swim

well. It is

marvellous how fully instinct

makes these birds independent. The parents do not take them to the

water and

teach them to swim. They haven't even the example of the old birds,

which stay

behind to moult. At an early age they become independent of their own

parents,

and earn their living by hunting any old bird they find. Though they

have spent

their lives on land, and only know that food is something found in an

old

bird's throat, when the time comes they leave the land and plunge

boldly into

the sea, untaught, to get their living by straining crustacea out of

the water

in the same way as the whale does. Some of our

party reported that they

saw penguins teaching the young to swim, but if this ever happens it is

not

general. Time and again the young have been watched leaving as

described,

entirely on their own. At that season nearly all the old birds are in

the moult

and never venture into the water. Like the

Emperor, the Adelie is fond

of travelling when family cares are off his mind. The great blizzard

which

wiped out half the rookery left hundreds of old birds free. They began

to

explore the adjacent country in bands. The round of the lakes was a

favourite

trip and broad -beaten roads marked this route. Tracks also led to the

summits

of some of the hills, though the short-sighted Adelie could hardly go

there for

the view. There was no

general trek

southwards, such as the Emperors made, yet the Southern Party found

tracks of

two at a distance of some eighty miles from the sea. NEBUCHADNEZZAR

AND NICODEMUS These names

dignified two penguin

chicks. While chaos reigned in the rookery I found them exhausted and

covered

with mire, having been hunted and pecked through the rookery. They were

taken

to the house, put in a large cage in the porch, and fed by hand with

sardines

and fish-cakes. The feeding was disagreeable. They didn't like the food

and

shook it out of their bills in disgust. So it was necessary to force it

down

their throats till it was beyond their reach. In a few days

they became quite tame

and recognised those who fed them. Familiar only with our peculiar

method of

feeding them, one of them indicated when he was hungry by taking my

finger into

his bill. We shortened their names to Nebby and Nicky, and they

answered to

them, but they answered equally readily to the common name of Bill. The

sounds

of the rookery reached them and sometimes greatly excited them and they

made

desperate efforts to get through the netting of their cage. At these

times we

would take them out for a walk. They made no attempt to go to the

rookery, and

were rather frightened.  PENGUINS LISTENING TO THE GRAMOPHONE DURING THE SUMMER Nebuchadnezzar

was a very friendly

little fellow, and would follow me about outside, and come running when

called.

The feeding was unnatural, and for this reason, doubtless, in a few

weeks they

died. THE

RINGED

PENGUIN A single ringed penguin appeared at Cape Royds at the end of the breeding-season, just as the Adelies were beginning to moult. No ringed penguin had been seen in this part of the Antarctic before. It was evidently a stray one which had come ashore to moult. It is about the same size as the Adele, but is more agile. It was at the season when the young Adelies go off to sea. At a little distance the ringed penguin, among a crowd of old Adelies, looked somewhat like a young Adelie with the white throat. I picked him up by the legs to investigate. To my surprise he curled round and bit me on the hand. An Adelie could not do so. A closer examination showed what he was. |