CHAPTER V

THE FAIR OF HAROM-SZÖLÖHOZ

The village of Harom-Szölöhoz lies on

the edge of the plain, where the rolling lands sweep toward the hills and those

in turn to the mountains.

Many of the men of the village were

sheep or cattle herders, as Emeric Semeyer, living with their herds and seldom

returning home save for high days and holidays. Others dwelt in the villages

and worked in the grain fields, while still others worked in the salt mines

each year for some months at least, for the salt mines of Hungary are famous

the world over, and employ many labourers.

It was a pleasant little village. In

the centre was an open space around which was clustered the church, with the

town house and the larger houses. All the cottages were white-washed, and had

gray-shingled roofs. Some of them had gay little flower gardens and a few had

trees planted by the doorway. Their shade is not needed, for though the sun is

hot, there is always the szöhördo to sit in. This is a seat placed under the

eaves which always overhang at one side of the roof. Here often the firewood is

stacked and one log serves as a seat upon which the old people may sit and

gossip, protected alike from sun and rain.

Upon the doorway of Aszszony

Semeyer's house were carved some tulips, a pattern much used in Hungary. In the

porch of the house dried kukurut and paprika hung in long ribbons to dry. The

front door opened into the kitchen where the soup pot simmered upon the huge

brick stove. Many of the cottages in this part of Hungary have but one room,

but Aszszony Semeyer was rich and she had two rooms and a loft above. She kept

the house wonderfully clean, yet she always seemed to have plenty of time to

sit at the window and embroider varrotas. The varrotas are Hungarian embroideries

worked with red and black and blue threads upon linen cloth the colour of pale

ochre. The thread and linen is woven by the women, and in nearly every cottage

in the village some one may be seen seated at the window spinning, weaving, or

embroidering.

Aszszony Semeyer's father had been

one of the beres1 employed

by the Tablabiro,2 and he

had been able to leave his daughter, for he had no sons, a cottage and some

money, so that she was better off than many of the village people. This did not

keep her from working hard, for all Magyars are industrious and hard working.

She did not intend that any one under her care should be idle; and Banda Bela

found that he and Marushka must work if they were to eat.

"Now then, my sugars," she

said to them, "we shall see what there is for you to do! Some work there

must be for one and the other. But a square pane will not fit a round window,

so we must give you something that you can do out of doors. You, Banda Bela,

shall go to help the swine-herd, and Marushka shall be goose girl."

"Oh, I should like that!"

cried Marushka. "I think the geese are so funny and I like to see them

eat."

"You shall learn to embroider,

and, as you sit on the meadow watching the geese, you can place many stitches.

When you marry you will have whole chests full of embroideries, like any well

brought up maiden. Otherwise you will be shamed before your husband's people.

"Banda Bela, you shall go with

the swine-herd. That will keep you out of doors, and you will like that, I am

sure."

"I will try," said Banda

Bela. "But I have never worked."

"Quite time you learned,

then," said the good woman. "We will start in the morning. To-day you

and Marushka may go about the village and make yourselves at home. You will

find much to interest you. Come back when the big bell of the church rings.

That will be dinner time."

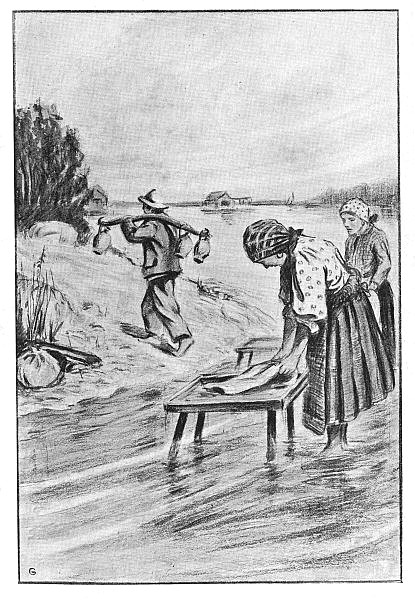

Washing in the river.

"Oh, Banda Bela, see those

people jumping up and down in the river!" said Marushka. "What are

they doing?"

"Washing, I think," said

Banda Bela. "See, they take a dress or an apron and put it in the stream

and tread on it, stamping it against the stones until the dirt all comes out,

then they rinse it out and put it in their wooden trays and take another piece

and wash it."

"I thought the wooden trays

were cradles for babies," said Marushka. "The Gypsies use them for

that."

"Yes, but I have seen them used

for many things," said Banda Bela. "The peasants carry goods to

market in them; in the city the baker boys use them to carry bread, washwomen

use them, and cooks use them to cut up meat for goulash or to chop paprika

in."

"Banda Bela, we're coming to

such a crowded place, — what are all those people doing?" asked Marushka,

pointing to a street which was crowded to overflowing with peasants, their

white costumes and gay aprons and jackets flashing about like bright birds in

the sunlight.

"It must be a market day,"

said the boy. "I have often seen the village markets when I was travelling

with my father. It might be fair time, and that is great fun! Let us go and

see, Marushka. They have lots of pretty things in the stalls."

The two children ran down the

street, which was filled with carts, covered with gay-coloured cloths, the

horses having been taken out and stabled elsewhere.

Stalls had been built up and down

the sides of the street and these were filled with fruit, melons, embroidery,

clothes, and wonderful crockery. Plates and jugs in gay colours and artistic

designs have been made by the peasants in this part of Hungary for hundreds of

years, and in the cottages one can see, hung along the walls under the rafters,

jugs, cups, and platters of great beauty. No peasant would part with his family

china, as he would feel disgraced unless he could display it up on his walls.

Ox carts lumbered down the streets,

the huge horns of the oxen frightening Marushka. Boys with huge hats, loose

white shirts, and trousers above the ankles, bare-footed girls and girls in top

boots, men and women, geese, pigs, horses, and cows, all crowded into the

square, where were the church with its white spire and golden cross, the

magistrate's house, and the inn named "Harom Szölöhoz" as its three

bunches of grapes above the door showed.

"Banda Bela," said

Marushka, "what are those women sitting behind those red and yellow pots

for? They look so funny with the great flat hats on their heads."

"They are cooking," said

Banda Bela. "I have seen these village fairs when I used to travel with my

father. In the bottom of those pots is burning charcoal upon which a dish is

set. In the dish they cook all kinds of things, frying meat in bacon fat,

making goulash and anything else a

customer may want."

"Isn't that funny!" said

Marushka, whose idea of cookery was the Gypsy fire-pot over a fire of sticks.

"What lovely frocks the girls wear! I like those boots with the bright red

tops, too, — I wish I had some," and she looked down discontentedly at her

ten little bare toes. Banda Bela laughed at her.

"You're a funny little bit of a

Marushka," he said. "Yesterday you hadn't a frock to your name, only

a little rag of a shirt, and you were all dirty and your hair had never been

combed. Now you have a pretty dress and an embroidered apron, and hair like a

high-born princess, yet you are not satisfied, but must have top boots! They

would pinch and hurt your feet terribly and cramp your toes so that you

couldn't wiggle them at all. After you had worn boots awhile your toes would

get so stiff that you couldn't use them as fingers as we do. People who always

wear boots cannot even pick up anything with their toes. If they want a stick

or anything that has fallen to the ground they have to bend the back and stoop

to pick it up with the fingers."

Marushka looked thoughtful for a

moment, her little toes curling and wriggling as she dug them into the sand,

then she said:

"But the boots are so pretty,

Banda Bela, I would like them!" The boy laughed.

"You will have to have them

someway, little sister," he said. "And one of those bright little

jackets, too, since you so much like to be dressed up like a fine bird."

"Why do some of the women wear

jackets and some not, and some of them such queer things on their heads?"

asked Marushka.

"This fair brings people from

all around and there are many kinds of people in Hungary," he said.

"Those tall straight men with faces all shaved except for the waxed

moustache are Magyars, while the fair-haired fellows who look as if they didn't

care about their clothes and slouch around are called Slövaks. The girls who

wear those long, embroidered, white robes, sandals on their feet and black

kerchiefs on their heads, are Roumanians. The Magyar girls wear

gold-embroidered aprons, big white sleeves and zouave jackets, and the boots

you like so much."

"I am a Magyar," said

Marushka, tossing her head proudly. "All but the boots."

"High-born Princess, boots you

shall have," laughed Banda Bela. "But how?" He knit his brows,

as they stopped at a stall where boots were displayed for sale. "I

know!" he cried, while Marushka looked longingly at the boots. "I

shall play for them."

His violin was under his arm, and he

raised it to his chin, tuned it softly, and quickly began a little tune.

Hungarians love music and it was but a moment before a crowd gathered around.

He played a gay little song, "Nezz

roysám a szemembe," one of the old Magyar love songs in which a lover

implores his sweetheart to look into his eyes and read there that for him she

shines like a star in the blue of heaven, and when he had finished everyone

cried for more. This time he whisked into a dance tune and feet patted in time

to the music and faces were fairly wreathed in smiles. When he stopped with a

gay flourish, everybody cried, "More, boy, more!" and Banda Bela

smiled happily as one in the crowd tossed him a krajczar.3 He took off his cap and passed it around

among the crowd. Many a krajczar fell

into it and one silver piece came from a Magyar officer, a tall fine-looking

man with a sad face, who stood on the edge of the crowd.

"Who are you, boy, and why do

you play? Do you need money?" asked the officer.

"Not for myself, Your Gracious

Highness, but the little one wishes red-topped boots and also a jacket,"

said the boy simply.

"These of course she must

have," said the officer, with a smile which lighted up his sad face.

"Where is this little sister of yours? At home with her mother?"

"No, Most High-Born

Baron," said Banda Bela. "The mother I have not, but Aszszony Semeyer

is very kind to us, and Marushka is here with me. That little maid by the

cooking stall."

"She is a fair little maid, of

course she must have her boots," said the officer. "But you have

earned them, for your music is like wine to empty hearts. What is your name,

boy, and where do you live?"

"My name is Banda Bela, Most

Gracious Baron. I live since yesterday at the house of Emeric Semeyer. My

father was Gergeley Banda, the musician, now dead."

"I have often seen and heard

your father in Buda-Pest," said the officer kindly, laying his hand on the

boy's shoulder. "You will play as well as he did if you keep on."

Banda Bela's eyes shone.

"That would please me more than

anything else in all the world," he said. "I think now I have enough

for Marushka's boots, so I need not play more, save one thing for the pleasure

of those who have paid me. I will play a song of my fathers," and he

played a gentle little melody, with a sad, haunting strain running through it,

which brought tears to the eyes.

"Boy, you are a genius! What is

that?" asked the baron when he had finished.

"It is called the 'Lost

One,'" said Banda Bela. "The little song running through it is of a

child who has been lost from home. The words are:

"The

hills are so blue,

The sun

so warm,

The wind

of the moor so soft and so kind!

Oh, the

eyes of my mother,

The

warmth of her breast,

The

breath of her kiss on my cheek, alas!"

The officer put a whole silver

dollar in the boy's hand and turned away without a word, and Banda Bela

wondered as he saw tears in the stern eyes.

Then Marushka got her boots and her

jacket and Banda Bela bought some new strings for his violin, and a little box

of sugar jelly which he took to Aszszony Semeyer, and to her also he gave the

store of krajczar left after his

purchases had been made.

1 Labourers employed by the year.

2 Lord of the estate.

3 Small coin.

|