CHAPTER VII

THE UNEXPECTED

Aszszony

Semeyer's

brother-in-law had a large vineyard and, when it came time for the vintage, the

good woman drove the children over to her brother's farm. The grapes grew in

long lines up and down the hillside where the sun was strongest. White carts,

drawn by white oxen, were driven by white-frocked peasants. All were decked

with grape leaves, all had eaten golden grapes until they could eat no more,

for the great bunches of rich, yellow grapes are free to all at vintage time.

From these golden grapes is made the amber-hued "Riesling," and the

children enjoyed very much helping to tread the grapes, for the wine is made in

the old-fashioned way, the grapes being cast into huge vats and trod upon with

the feet till the juice is entirely pressed out. The peasants dance gaily up

and down upon the grapes, tossing their arms above their heads and making great

pleasure of their work.

After the long, happy, sunny day the

white cart of Aszszony Semeyer joined the line of carts which wound along from

the vineyard, filled with gay toilers. At her brother's farm they stayed all

night, for the vintage dance upon the grass under the golden glow of the harvest

moon was too fair a sight to miss.

They stayed, too, for the

nut-gathering. Hungarian hazel nuts are celebrated the world over, and the

nutting was as much a fête as had been the vintage. This was the last frolic of

the year, and the children went back to Harom Szölöhoz to work hard all winter.

Banda Bela still helped the swine-herd, but Marushka was no longer a goose

girl. Aszszony Semeyer had grown very fond of the little girl and spent long

hours teaching her to sew and embroider. Many salt tears little Marushka shed

over her Himmelbelt, or marriage

bed-cover. Every girl in Hungary is supposed to have a fine linen bedspread

embroidered ready to take to her home when she is married. It takes many months

to make one of them, and Marushka's was to be a very elaborate one.

The linen was coarse, but spun from

their own flax by Aszszony Semeyer herself. In design Marushka's Himmelbelt was wonderful. The edge was

to be heavily embroidered in colours, and in one corner was Marushka's name, a

space being left for the day of the wedding. In the centre was a wedding hymn

which was embroidered in gay letters, and began:

"Blessed by the Saints and God above I'll be

If I do wed the man who loveth me;

Then may my home be full of peace and rest,

And I with goodly sons and daughters blest!"

Marushka worked over it for hours

and grew to fairly hate the thought of marrying.

"I shall never, never

marry," she sobbed. "I shall never finish this horrid old Himmelbelt and I suppose I can't be

married without it."

Banda Bela sympathized with her and

often played for her while she worked. Through the long winter the children

learned to read and write, for all children are compelled to go to school in

Hungary, and the Gypsies are the only ones who escape the school room.

Marushka learned very fast. Her mind

worked far more quickly than did Banda Bela's, though he was so much older.

There was nothing which Marushka did not want to know all about; earth, air,

sky, water, sun, wind, people, — all were interesting to her.

"The wind, Banda Bela, whence

comes it?" she would ask.

"It is the breath of God,"

the boy would answer.

"And the sun?"

"It is God's kindness."

"But the storms, with the

flashing lightning and the terrible thunder?"

"It is the wrath of Isten, the

flash of his eye, the sound of his voice."

"But I like to know what makes the things," said Marushka.

"It is not enough to say that everything is God. I know He is back of

everything. Aszszony Semeyer told me that, but I want to know the how of what He does."

"I think we cannot always do

just what we like," said Banda Bela calmly. "I have found that out

many times, so it is best not to fret about things but to live each day by

itself." At this philosophy Marushka pouted.

One afternoon in the summer the

children asked for permission to go to the woods, and Aszszony Semeyer answered

them:

"Yes, my pigeons, go; the sky

is fair and you have both been good children of late, — go, but return

early."

They had a happy afternoon playing

together upon the hills which were so blue with forget-me-nots that one could

hardly see where the hilltops met the sky. Marushka made a wreath of them and

Banda Bela crowned her, twining long festoons of the flowers around her neck

and waist, until she looked like a little flower fairy. They wandered homeward

as the sun was setting, past the great house on the hill, and Maruskha said:

"I wonder if the High-Born

Baron and his gracious lady will soon be coming home? In the village they say

that they always come at this time of the year. Do you remember how beautiful

the High-Born Baroness looked at Irma's wedding?"

"She was beautiful and kind,

and sang like a nightingale," said Banda Bela. "Come, Marushka, we

must hurry, or Aszszony Semeyer will scold us for being late!"

As they neared the village they

heard a noise and a strange scene met their gaze! A yoke of white oxen blocked

the way; several black and brown cattle had slipped their halters and were

running aimlessly about tossing their horns; seventeen hairy pigs ran hither

and thither, squealing loudly, and all the geese in town seemed to be turned

loose, flapping their wings and squawking at the top of their voices. Children

were dashing around, shouting and screaming, in their efforts to catch the

different animals, while the grown people, scarcely less disturbed, tried in

vain to silence the din.

"They are frightened by the

machine of the High-Born Baron, Marushka," said Banda Bela. "See,

there it is at the end of the street. I have seen these queer cars in

Buda-Pest, but none has ever been in this little village before, so it is no

wonder that everyone is afraid. There, the men have the cattle quiet, but the

geese and the pigs are as bad as ever."

"Let us run and lead them out,

Banda Bela," cried Marushka. "You can make the pigs follow you and I

can quiet the geese. It is too bad to have the homecoming of their High-Born

Graciousnesses spoiled by these stupids!" Marushka dashed into the throng

of geese calling to them in soft little tones. They recognized her at once and

stopped their fluttering as she called them by the names she had given them

when she was goose girl and they all flocked about her. Then she sang a queer

little crooning song, and they followed her down the street as she walked

toward the goose green, not knowing how else to get them out of the way.

Banda Bela meantime was having an

amusing time with his friends the pigs. They were all squealing so loudly that

they could scarcely hear his voice, so he bethought himself of his music and

began to play. It was but a few moments before the piggies heard and stopped to

listen. Banda Bela had played much when he was watching the pigs on the moor,

and his violin told them of the fair green meadow where they found such good

things to eat, and of the river's brink with its great pools of black slime in

which to wallow. They stopped their mad dashing about and gathered around the

boy, and he, too, turned and led them from the village.

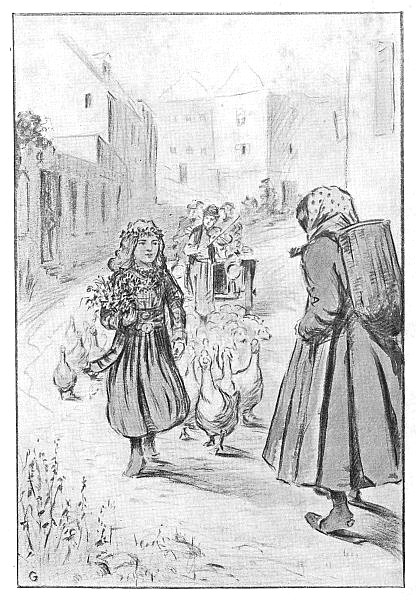

It was a funny sight, this village

procession. First came Marushka in her little peasant's costume, decked with

her wreath and garlands of forget-me-nots, and followed by her snow-white

geese. Next, Banda Bela, playing his violin and escorting his pigs, while last

of all came the motor car of the High-Born Baron, the Baron looking amused, the

Baroness in spasms of laughter.

"Oh, Léon," she cried.

"Could our friends who drive on the Os Budavara1 see us now!

Such a procession! That child who leads is the most beautiful little creature

and so unconscious, and the boy's playing is wonderful."

"First came

Marushka"

"They must be the Gypsy

children Aszszony Semeyer adopted. We saw them when we were here last

year," replied her husband. "What a story this would make for the

club! We must give these children a florin for their timely aid."

But the children, unconscious of

this pleasant prospect, led their respective friends back into the village by

another way, so that it was not until the next day that the

"High-Born" ones had a chance to see them, and this time in an even

more exciting adventure than that of the village procession. It was the motor

car again which caused the trouble.

Marushka and Banda Bela had been

sent on an errand to a farm not far from the village and were walking homeward

in the twilight. Down the road came a peasant's cart just as from the opposite

direction came the "honk-honk" of the Baron's motor. Such a sight had

never appeared to the horses before in all their lives. They reared up on their

hind legs, pawing the air wildly as the driver tried to turn them aside to let

the motor pass. A woman and a baby sat in the cart, and, as the horses became

unmanageable and overturned the cart into the ditch, the woman was thrown out

and the baby rolled from her arms right in front of the motor. The mechanician

had tried to stop his car, but there was something wrong with the brake and he

could not stop all at once. Marushka saw the baby. If there was one thing she

loved more than another it was a baby. She saw its danger and in a second she

dashed across the road, snatched up the little one and ran up the other side of

the road just as the motor passed over the spot where the baby had fallen.

"Marushka," cried Banda

Bela as he ran around the motor. "Are you hurt?"

"Brave child!" cried the

Baron, who sprang from his car and hurried to the group of frightened peasants.

"Are you injured?"

"Not at all, Most Noble

Baron," said Marushka, not forgetting to make her courtesy, though it was

not easy with the baby in her arms.

The child's mother had by this time

picked herself out of the ditch and rushed over to where Maruskha stood, the

baby still in her arms and cooing delightedly as he looked into the child's

sweet face, his tiny hand clutching the silver medal which always hung about

Marushka's neck. The mother snatched the baby to her breast and, seating

herself by the roadside, she felt all over its little body to see if it was

hurt.

"You have this brave little

girl to thank that your baby was not killed," said the Baron. The woman

turned to Marushka.

"I thank you for — " she

began, stopped abruptly, and then stared at the little girl with an expression

of amazement. "Child, who are you?" she demanded.

"Marushka," said the

little girl simply. The woman put her hand to her head.

"It is her image," she

muttered. "Her very self!"

The Baroness had alighted from the

motor and came up in time to hear the woman's words.

"Whose image?" she

demanded sharply.

The woman changed colour and put her

baby down on the grass.

"The little girl looks like a

child I saw in America," she stammered, her face flushing.

"Was she an American child?"

demanded the Baroness.

"Oh, yes, Your

Graciousness," said the woman hastily. "Of course, she was an

American child."

"Now I know that you are

speaking falsely," said the Baroness. "This little one looks like no

American child who was ever born. Léon," turning to her husband, "is

this one of your peasants?" Then she added in a tone too low to be heard

by anyone but her husband, "I know that she can tell something about this

little girl. Question her."

The Baron turned to the woman and

said:

"This little girl saved your

baby's life. Should you not do her some kindness?"

"What could I do for her, Your

High-Born Graciousness?" the woman asked.

"That I leave to your good

heart." The Baron had not dwelt upon his estates and managed his peasants

for years without knowing peasant character. Threats would not move this woman,

that he saw in a moment.

"She is a Gypsy child,"

the woman said sullenly.

Banda Bela spoke suddenly, for he

had come close and heard what was said.

"That she is not! She is

Magyar. Deserted by the roadside, she was cared for by Gypsy folk. Does she

look like a Gypsy? Would a Gypsy child wear a Christian medal upon her

breast?" The boy's tone was sharp. Marushka heard nothing. She was playing

with the baby.

The woman looked from Marushka to

the baby, then at the Baron, hesitating. "Let me see your pretty medal,

child," she said at length, and Marushka untied the string and put the

medal in the woman's hand.

"I used to think it was my

mother, but now I know it is Our Lady," said Marushka gently. The woman

looked at it for a moment, then gave it back to the little girl and stood for a

moment thinking.

"High-Born Baron," she

said at last, "I will speak. Those it might harm are dead. The little girl

who saved my baby I will gladly serve, but I will speak alone to the ears of

the Baron and his gracious lady."

"Very well," said the

Baron as he led the woman aside.

"Škultéty Yda is my name, Your

Graciousness," she said. "I was foster-sister to a high-born lady in

the Province in which lies Buda-Pest. I loved my mistress and after her

marriage I went with her to the home of her husband, a country place on the

Danube. There I met Hödza Ludevit, who wished to marry me and take me to

America, for which he had long saved the money. He hated all nobles and most of

all the High-Born Count, because the Count had once struck him with his riding

whip. Then the Countess' little daughter came and I loved her so dearly that I

said that I would never part from her. Ludevit waited for me two years, then he

grew angry and said, 'To America I will go with or without you.' Then he stole

the little baby and sent me word that he would return her only on condition

that I go at once to America with him. To save the little golden-haired baby I

followed him beyond the sea to America. He swore to me that he had returned

little Marushka to her parents.

"The Count traced us to America

thinking we might have taken the child with us, and then I learned that the

baby had never been sent home. My wicked husband had left it by the roadside and

what had become of it no one knew. It turned my heart toward my husband into

stone. Now he is dead and I have brought my own baby home, but my family are

all dead and I have no place to go. These people were kind to me on the ship,

so I came to them, hoping to find work to care for my baby, since all my money

was spent in the coming home. This little girl who saved my baby I know to be

the daughter of my dear mistress." She stopped.

"How do you know it?"

demanded the Baroness.

"Your High-Born Graciousness,

she is her image. There is the same corn-coloured hair, the same blue eyes, the

same flushed cheek, the same proud mouth, the same sweet voice."

"What was the name of your

lady?" interrupted the baroness, who had been looking fixedly at Marushka,

knitting her brows. "The child has always reminded me of someone; who it

is I cannot think."

"The foster sister whom I loved

was the Countess Maria Andrássy."

"I see it," cried the

Baroness. "The child is her image, Léon. I have her picture at the castle.

You will see at once the resemblance. I have not seen Maria since we left

school. Her husband we see often at Court. I had heard that Maria had lost her

child and that since she had never left her country home. I supposed the child

was dead. This little Marushka must be Maria Andrássy."

"We must have proofs,"

said the Baron.

"Behold the medal upon the

child's neck," said Yda. "It is one her mother placed there. I myself

scratched with a needle the child's initials 'M. A.' the same as her mother's.

The letters are still there; and if that is not enough there is on the child's

neck the same red mark as when she was born. It is up under her hair and her

mother would know it at once."

"The only way is for her mother

to see her and she will know. This Gypsy boy may be able to supply some missing

links. We shall ask him," said the Baron. When Banda Bela was called he

told simply all that he knew about Marushka and all that old Jarnik had told

him.

"There is no harm coming to

her, is there?" he asked anxiously, and the Baroness said kindly:

"No, my boy, no harm at all,

and perhaps much good, for we think that we have found her people." Banda

Bela's face clouded. "That would make you sad?" she asked.

"Yes and no, Your

Graciousness," he answered. "It would take my heart away to lose Marushka

for whom I have cared these years as my sister, but I know so well the sadness

of having no mother. If she can find her mother, I shall rejoice."

"Something good shall be found

for you, too, my lad." The Baroness smiled at him, but he replied simply:

"I thank Your High-Born

Graciousness. I shall still have my music."

The Baroness flashed a quick glance

at him. "I understand you, boy; nothing can take that away from one who

loves it. Now take the little one home, and to-morrow we shall come to see

Aszszony Semeyer about her. In the meantime, say not one word to the little

girl for fear she be disappointed if we have made a mistake."

"Yes, Your High-Born

Graciousness," and Banda Bela led Marushka away, playing as they went down

the hill the little song of his father.

"The hills are so blue,

The sun so warm,

The wind of the moor

so soft and so kind!

Oh, the eyes of my

mother,

The warmth of her

breast,

The breath of her

kiss on my cheek, alas!"

1 Celebrated drive in Buda-Pest.

|