|

XII:

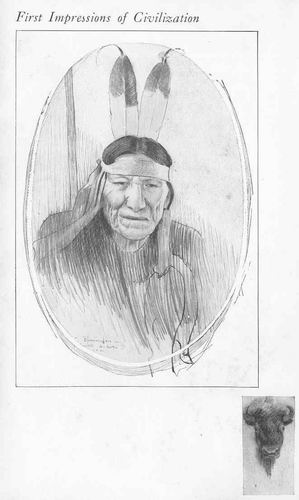

First Impressions of Civilization

I WAS

scarcely old enough to know anything definite about the “Big Knives,”

as we called the white men, when the terrible Minnesota massacre broke

up our home and I was carried into exile. I have already told how I was

adopted into the family of my father’s younger brother, when my father

was betrayed and imprisoned. We all supposed that he had shared the

fate of those who were executed at Mankato, Minnesota.

Now the

savage philosophers looked upon vengeance in the field of battle as a

lofty virtue. To avenge the death of a relative or of a dear friend was

considered a great deed. My uncle, accordingly, had spared no pains to

instill into my young mind the obligation to avenge the death of my

father and my older brothers. Already I looked eagerly forward to the

day when I should find an opportunity to carry out his teachings.

Meanwhile, he himself went upon the war-path and returned with scalps

every summer. So it may be imagined how I felt toward the Big Knives!

On the

other hand, I had heard marvelous things of this people. In some things

we despised them; in others we regarded them as wakan (mysterious),

a race whose power bordered upon the supernatural. I learned that they

had made a “fireboat.” I could not understand how they could unite two

elements which cannot exist together. I thought the water would put out

the fire, and the fire would consume the boat if it had the shadow of a

chance. This was to me a preposterous thing! But when I was told that

the Big Knives had created a “fire-boat-walks-on-mountains” (a

locomotive) it was too much to believe.

“Why,”

declared my informant, “those who saw this monster move said that it

flew from mountain to mountain when it seemed to be excited. They said

also that they believed it carried a thunder-bird, for they frequently

heard his usual war-whoop as the creature sped along!”

Several

warriors had observed from a distance one of the first trains on the

Northern Pacific, and had gained an exaggerated impression of the

wonders of the pale-face. They had seen it go over a bridge that

spanned a deep ravine and it seemed to them that it jumped from one

bank to the other. I confess that the story almost quenched my ardor

and bravery.

Two or

three young men were talking together about this fearful invention.

“However,”

said one, “I understand that this fire-boat-walks-on-mountains cannot

move except on the track made for it.”

Although a

boy is not expected to join in the conversation of his elders, I

ventured to ask: “Then it cannot chase us into any rough country?”

“No, it

cannot do that,” was the reply, which I heard with a great deal of

relief.

I had seen

guns and various other things brought to us by the French Canadians, so

that I had already some notion of the supernatural gifts of the white

man; but I had never before heard such tales as I listened to that

morning. It was said that they had bridged the Missouri and Mississippi

rivers, and that they made immense houses of stone and brick, piled on

top of one another until they were as high as high hills. My brain was

puzzled with these things for many a day. Finally I asked my uncle why

the Great Mystery gave such power to the Washechu (the rich) —

sometimes we called them by this name — and not to us Dakotas.

“For the

same reason,” he answered, “that he gave to Duta the skill to make fine

bows and arrows, and to Wachesne no skill to make anything.”

“And why do

the Big Knives increase so much more in number than the Dakotas?” I

continued.

“It has

been said, and I think it must be true, that they have larger families

than we do. I went into the house of an Eashecha (a German), and I

counted no less than nine children. The eldest of them could not have

been over fifteen. When my grandfather first visited them, down at the

mouth of the Mississippi, they were comparatively few; later my father

visited their Great Father at Washington, and they had already spread

over the whole country.”

“Certainly

they are a heartless nation. They have made some of their people

servants — yes, slaves! We have never believed in keeping slaves, but

it seems that these Washechu do! It is our belief that they painted

their servants black a long time ago, to tell them from the rest, and

now the slaves have children born to them of the same color!

“The

greatest object of their lives seems to be to acquire possessions — to

be rich. They desire to possess the whole world. For thirty years they

were trying to entice us to sell them our land. Finally the outbreak

gave them all, and we have been driven away from our beautiful country.

“They are a

wonderful people. They have divided the day into hours, like the moons

of the year. In fact, they measure everything. Not one of them would

let so much as a turnip go from his field unless he received full value

for it. I understand that their great men make a feast and invite many,

but when the feast is over the guests are required to pay for what they

have eaten before leaving the house. I myself saw at White Cliff (the

name given to St. Paul, Minnesota) a man who kept a brass drum and a

bell to call people to his table; but when he got them in he would make

them pay for the food!

“I am also

informed,” said my uncle, “but this I hardly believe, that their Great

Chief (President) compels every man to pay him for the land he lives

upon and all his personal goods — even for his own existence — every

year!” (This was his idea of taxation.) “I am sure we could not live

under such a law.

“When the

outbreak occurred, we thought that our opportunity had come, for we had

learned that the Big Knives were fighting among themselves, on account

of a dispute over their slaves. It was said that the Great Chief had

allowed slaves in one part of the country and not in another, so there

was jealousy, and they had to fight it out. We don’t know how true this

was.

“There were

some praying-men who came to us some time before the trouble arose.

They observed every seventh day as a holy day. On that day they met in

a house that they had built for that purpose, to sing, pray, and speak

of their Great Mystery. I was never in one of these meetings. I

understand that they had a large book from which they read. By all

accounts they were very different from all other white men we have

known, for these never observed any such day, and we never knew them to

pray, neither did they ever tell us of their Great Mystery.

“In war

they have leaders and war-chiefs of different grades. The common

warriors are driven forward like a herd of antelopes to face the foe.

It is on account of this manner of fighting — from compulsion and not

from personal bravery — that we count no coup on

them. A lone warrior can do much harm to a large army of them in a bad

country.”

It was this

talk with my uncle that gave me my first clear idea of the white man.

I was

almost fifteen years old when my uncle presented me with a flint-lock

gun. The possession of the “mysterious iron,” and the explosive dirt,

or “pulverized coal,” as it is called, filled me with new thoughts. All

the war-songs that I had ever heard from childhood came back to me with

their heroes. It seemed as if I were an entirely new being — the boy

had become a man!

“I am now

old enough,” said I to myself, “and I must beg my uncle to take me with

him on his next war-path. I shall soon be able to go among the whites

whenever I wish, and td avenge the blood of my father and my brothers.”

I had

already begun to invoke the blessing of the Great Mystery. Scarcely a

day passed that I did not offer up some of my game, so that he might

not be displeased with me. My people saw very little of me during the

day, for in solitude I found the strength I needed. I groped about in

the wilderness, and determined to assume my position as a man. My

boyish ways were departing, and a sullen dignity and composure was

taking their place.

The thought

of love did not hinder my ambitions. I had a vague dream of some day

courting a pretty maiden, after I had made my reputation, and won the

eagle feathers.

One day,

when I was away on the daily hunt, two strangers from the United States

visited our camp. They had boldly ventured across the northern border.

They were Indians, but clad in the white man’s garments. It was as well

that I was absent with my gun.

My father,

accompanied by an Indian guide, after many days’ searching had found us

at last. He had been imprisoned at Davenport, Iowa, with those who took

part in the massacre or in the battles following, and he was taught in

prison and converted by the pioneer missionaries, Drs. Williamson and

Riggs. He was under sentence of death, but was among the number against

whom no direct evidence was found, and who were finally pardoned by

President Lincoln.

When he was

released, and returned to the new reservation upon the Missouri river,

he soon became convinced that life on a government reservation meant

physical and moral degradation. Therefore he determined, with several

others, to try the white man’s way of gaining a livelihood. They

accordingly left the agency against the persuasions of the agent,

renounced all government assistance, and took land under the United

States Homestead law, on the Big Sioux river. After he had made his

home there, he desired to seek his lost child. It was then a dangerous

undertaking to cross the line, but his Christian love prompted him to

do it. He secured a good guide, and found his way in time through the

vast wilderness.

As for me,

I little dreamed of anything unusual to happen on my return. As I

approached our camp with my game on my shoulder, I had not the

slightest premonition that I was suddenly to be hurled from my savage

life into a life unknown to me hitherto.

When I

appeared in sight my father, who had patiently listened to my uncle’s

long account of my early life and training, became very much excited.

He was eager to embrace the child who, as he had just been informed,

made it already the object of his life to avenge his father’s blood.

The loving father could not remain in the teepee and watch the boy

coming, so he started to meet him. My uncle arose to go with his

brother to insure his safety.

My face

burned with the unusual excitement caused by the sight of a man wearing

the Big Knives’ clothing and coming toward me with my uncle.

“What does

this mean, uncle?”

“My boy,

this is your father, my brother, whom we mourned as dead. He has come

for you.”

My father

added: “I am glad that my son is strong and brave. Your brothers have

adopted the white man’s way; I came for you to learn this new way, too;

and I want you to grow up a good man.”

He had

brought me some civilized clothing. At first, I disliked very much to

wear garments made by the people I had hated so bitterly. But the

thought that, after all, they had not killed my father and brothers,

reconciled me, and I put on the clothes.

In a few

days we started for the States. I felt as if I were dead and traveling

to the Spirit Land; for now all my old ideas were to give place to new

ones, and my life was to be entirely different from that of the past.

Still, I

was eager to see some of the wonderful inventions of the white people.

When we reached Fort Totten, I gazed about me with lively interest and

a quick imagination.

My father

had forgotten to tell me that the fire-boat-walks-on-mountains had its

track at Jamestown, and might appear at any moment. As I was watering

the ponies, a peculiar shrilling noise pealed forth from just beyond

the hills. The ponies threw back their heads and listened; then they

ran snorting over the prairie. Meanwhile, I too had taken alarm. I

leaped on the back of one of the ponies, and dashed off at full speed.

It was a clear day; I could not imagine what had caused such an

unearthly noise. It seemed as if the world were about to burst in two!

I got upon

a hill as the train appeared. “O!” I said to myself, “that is the

fire-boat-walks-on-mountains that I have heard about!” Then I drove

back the ponies.

My father

was accustomed every morning to read from his Bible, and sing a stanza

of a hymn. I was about very early with my gun for several mornings; but

at last he stopped me as I was preparing to go out, and bade me wait.

I listened

with much astonishment. The hymn contained the word Jesus. I

did not comprehend what this meant; and my father then told me that

Jesus was the Son of God who came on earth to save sinners, and that it

was because of him that he had sought me. This conversation made a deep

impression upon my mind.

Late in the

fall we reached the citizen settlement at Flandreau, South Dakota,

where my father and some others dwelt among the whites. Here my wild

life came to an end, and my school days began.

THE

END

Web and Book design,

Web and Book design,

copyright,

Kellscraft Studio

1999-2003

(Return

to Web Text-ures) |