| Web

and Book

design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2009 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

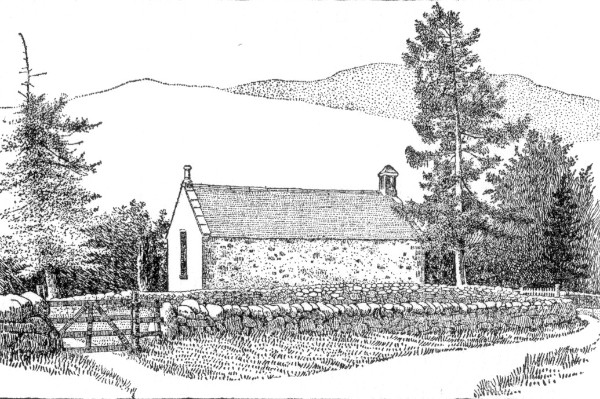

XII

THE SABBATH AND THE KIRKS  A Garden Rose OF the several leading religious denominations in Scotland, that known as the Free Kirk possessed for me the greatest attraction. I must, however, confess I am only familiar with religious Scotland as a stronghold of Presbyterianism. There were three branches of this faith — the Established Kirk, the 'U.P.'s' or United Presbyterians, and the Free Kirk. But the last seemed to have the most honest independence, vitality, and enterprise, and to draw to its pulpit, as a rule, the strongest and most original men. As typical a Free Kirk as any which I attended was one in a certain glen of the southern Highlands. The building was of stone, very plain, and of modest size. In these things it was like most country churches; but the interior was not so characteristic, for it had been recently modernized, and had an inclined floor and steam heat. Still, the pews were uncushioned, and there was no organ. Indeed, organs are almost never found in rustic houses of worship, and are rarities even in the large towns. Service was supposed to begin at half-past eleven, but it was customary to allow some leisurely minutes of grace for the benefit of the belated. Shortly before the appointed hour, the little bell in the kirk cupola commenced a hurried tinkling, and the village ways, which hitherto had been very quiet and deserted, were enlivened by groups of soberly dressed worshippers faring on foot toward the church. On arriving at the edifice it was to be noticed that the men were in no haste to go inside, but lingered at the kirk gate or around the porch and visited. When the time for service came, and the bell ceased ringing, the outside loiterers would come stamping in. It was no wonder that their tread was emphatic, for their shoes were exceedingly sturdy, and the soles were well studded with heavy-headed nails. A pair of men's "strong-wearing boots" would weigh six pounds, and the projecting iron pegs number two hundred or more in each. The minister did not appear until the congregation, including late comers, were all in the pews. Then the door at the rear of the kirk opened, and he came rustling down the aisle in his robes. In front of the pulpit was an open space with a railing around it. There sat the members of the choir. Their leader, or "precentor," gave them the key-note when they were about to sing, and he beat time. Nearly every one in the congregation joined in the hymns, and the music was harmonious and pleasing, and the lack of an organ did not seem serious. The worshippers all had Bibles, and looked up the minister's texts and followed him in his Scripture readings with great faithfulness. There were two sermons, a short, simple one for the children, and a long one, various-headed and more or less theological, for the older hearers. Both discourses were vigorous and thoughtful, and showed the preacher to be a man of sense and ability. He was listened to attentively for the most part, about the only distractions being the occasional passing of snuff-boxes and the sounding blasts of noses that succeeded this ceremony. Not far from the pew I occupied on my first Sunday sat a venerable farmer, who, from time to time, took his snuff-box from his vest pocket and passed it to the elder in the seat behind, with the stealthy quiet and sidelong glance of a schoolboy doing something he ought not, on the sly. When the box returned to him, he indulged in a generous sniff himself, and then got out a great colored handkerchief; and it was a full minute before he had adjusted himself into his original watchfulness of the points of the sermon. I was told that this old farmer sometimes fell asleep and snored in church, and that of late, finding ordinary methods of inducing wakefulness insufficient, he had come to church generously provided with sweeties, on which he ruminated between snuff-takings. The gossips affirmed that he made such a noise cracking away at the sweeties after he got them between his teeth, that you could have heard him all over a church three times as large as the Free Kirk. This was perhaps an exaggeration, for I noted nothing of the sort, nor any serious propensity on his part to drowsiness. He certainly acquitted himself better than an old lady four seats in front of me. The service was long, and toward its close she nodded into a nap and lost her balance. There was a thump and a scrape, and then she started back erect. No one smiled at the episode, and it was apparently too common an occurrence to attract much attention. Previous to its remodelling, the Free Kirk had a gallery, but this had been for a long time superfluous, and it was torn out. Even with its reduced seating capacity, the kirk was far from crowded. Vacant pews were sadly numerous, where fifty years ago worshippers were so many that not only the body of the church was full, but some had to be seated in the aisles. In those days the glen was much more densely populated, and there were many little farms and cotter's houses scattered along the now lonely hillsides. The big farms have absorbed them, and the walls of the little houses have gone into stone fences or new byres on the large holdings that are at present customary. The cities and the new countries beyond the seas have drawn many people from the glen. In 1845 thirty families left at one time for America. But in spite of the diminished size of the congregation, the parishioners pay their preacher £180 a year, and give him the use of the manse in which he makes his home. This manse, in common with most of its kind, was a plain, two-story stone dwelling with a garden at one side that overflowed every summer with vegetables, small fruits, and flowers. Gravelled paths led to the doors, and there was a bit of lawn and some shade trees at the front, and the whole was enclosed by hedges. It was the habit of the Free Kirk minister to walk or drive on Sunday evenings to one of the outlying districts of the glen, and there conduct a meeting in some cottage or schoolhouse. On mild summer Sabbaths these little gatherings were often held in the open air. I attended one such. It was in a little field back of a row of cottages. Chairs were brought from the houses, and boards from a neighboring joiner's shop were laid from seat to seat, and twenty or thirty of us found places on them, while several boys sat on the grass by the hedge that was close behind. For the convenience of the preacher a white-spreaded stand was provided. We sang a number of times from Gospel Hymns, and the minister prayed, read from Scripture, and preached a short, practical sermon. Two great beeches, their leaves rustling in the light wind, overspread us, and the low sun looked underneath and brightened their gray trunks. Could any church be finer than this sylvan temple of nature? In what I saw of the U. P. Kirk, it was much like the Free, and there seemed no special reason why the two denominations should not unite, as I believe they have since throughout Scotland. But the Established Kirk, or "Kirk of Scotland," has an individuality of its own. Official recognition is given it by the government, and it is aided by a levy on the proprietors of the land. Yet because this tax is an indirect one, it does not provoke the discontent occasioned by tithes and church rates in England. To be sure, the landowners who pay the tax add it to the rentals, but as it does not appear as a separate item, its weight is not realized. The church of the Established sect which I recall most vividly was one in a well-settled country district that supported not only this but two or three dissenting churches. There was a time when a good deal of bitterness was felt between the government church and the dissenting branches; but in this particular community the ancient animosities had apparently died out. I sometimes heard the Established Kirk spoken of as "Auld Boblin" (Old Babylon), yet this mention was made jokingly, and there was no sharpness in the epithet. The church building was a low, gray stone structure standing well back from the highway at the end of a narrow lane — a lane paved with loose pebbles that made you feel as if you were doing penance as you walked over them. Coarse pebbles up to the size of a hen's egg were a favorite material for paths throughout the district. They even took the place of lawns, as, for instance, in front of the neighboring schoolhouse, where quite a space was overspread with them. The paths and approaches to all the local churches were treated in the same rude way, and once or twice a year the bedrels (sextons) were at great pains to scratch the walks over and pick out every bit of grass that had started on them. If there was any doubt before as to the stern material of which the walks were made, no such doubt could be entertained afterward. Round about the old church was the little parish burying-ground, with its frequent headstones and simple monuments, some of them recent and some so old that the markings on them were quite worn away. Perhaps the most impressive of them were certain ones marked with grewsome symbols, like skulls and crossbones, calculated to put the observer in a properly serious frame of mind. Few were reserved for the grave of a single individual. Usually each marked the burial-place of a family, and whenever one of the household died, a fresh name was carved at the bottom of the list already on the stone. But in the case of the humble majority in the parish, the graves had never been marked at all, and the bedrel in his digging often unearthed ancient bones, or struck the end of a coffin. On the pleasant summer Sunday that I attended the old church I was early, but the gate at the far end of the lane was thrown back, and the bedrel had completed arrangements for the arrival of the worshippers. Just inside the gate on the right-hand side was a little vestry, like a porter's lodge. Across the path, on a rustic bench under a beech tree, sat the gnarled old sexton. He looked as if he was there in solemn guard over the contribution plate which was on a stand immediately in front of him. No collection is taken up during service in the Scotch churches. A plate on a stand does duty instead; but as a rule this is just inside the entrance of the edifice, and not, as here, at the portals of the churchyard. Every one, male and female, old and young, seems to feel it a privilege or duty to drop a coin on the plate, and there is sure to be a goodly pile, though very likely mostly in coppers. I deposited my mite as I went through the Auld Kirk gate, and continued along the pebbles to the church. On looking in I decided I would prefer to sit in the loft (gallery), but how to get there was a problem. It was plain that within the church no way existed to gain the desired place unless one was athlete enough to climb the supporting pillars. I did not think that Presbyterianism would countenance such a performance on the part of its gallery worshippers, and I concluded to explore outside. By going around to the rear I found a narrow stone stairway, and I made the ascent to a tiny balcony that clung high on the wall. A door led from the balcony to the interior, and I soon had installed myself in a seat. Through the middle of the room below ran a single aisle, on each side of which were rows of narrow pews with backs so high and perpendicular it made one ache simply to look at them. Unhappily, the seats in the loft were built on the same plan — a fact I realized more and more emphatically as time went on. Everything was puritanically plain — bare plaster walls, and unpainted pews that were brown and worm-eaten with age. The floor was dirty and littered, and I could not help fancying its acquaintance with the broom dated back many months. This was indeed the case, as I learned later. Twice a year only was the church swept and cleaned, and it was then near the end of one of the undisturbed periods. Heat was supplied by a rude stove that sent a long black pipe elbowing up to the ceiling. The stove was placed just outside the overhang of the loft, and it apparently smoked at times, for the gallery-front and the ceiling above were blackened with soot.  An Exchange of Snuff None of the churches of the neighborhood had an organ, partly because it would have been difficult to find any one in the district who could play such an instrument, partly because the more old-fashioned people of the region thought an organ was irreligious, or at least that its music was not of a character suited for Sabbath use in a church. It was a sentiment of much the same sort that formerly condemned stoves, as smacking too much of worldly comfort. When the first church stove was introduced in the region, an elderly worshipper in one of the other churches said disapprovingly, "It is a great peety that their heirts are grown that cauld they maun hae a stove in the kirk." But a better reason for slowness in adopting artificial means of heating was that the fireplaces in common use in the homes were entirely inadequate for a large building, and it was a long time before a really practical stove could be had. The rear gable of the Auld Kirk was surmounted by a diminutive turret in which hung a bell. From it a rope dangled down the ivied wall, and the sexton, in calling the worshippers to service, stood below on the grass. The bell had a tinkling, unmusical sound, with about as much power in it as there is in a large handbell wielded at the beginning of school sessions or the close of recess by a New England district schoolmarm. Twelve o'clock was the service hour, and the kirk bell rang for several minutes preceding. Its summons was the signal for the visiting groups of people in the churchyard to come inside, and when the bell presently stopped its clamor, everything became very solemn and quiet. But there was no preacher in the high pulpit, and the treacherous-looking sounding-board hung over vacancy. The minutes dragged on, and the stiff seats grew steadily harder, and still no sign of a minister. Yet the congregation did not seem at all anxious. The place had very much the air of a prayer-meeting which is open for remarks that no one is. ready to offer. The people began to get sleepy, and made occasional shifts to find more restful positions. But at ten minutes past twelve the pastor came — a staid, comfortable-looking old gentleman in full, black robes, who padded in as complacently as if he was right on the dot. He climbed leisurely to the pulpit, got out his handkerchief and laid it convenient at his right hand, adjusted his books, and then put on his spectacles and gave out a psalm for us to sing. Behind a little desk under the eaves of the pulpit sat a young man who now rose to beat time and lead the singing. He kept up a marked swaying of the body to match the music, and in his efforts to strike the high notes properly, ran his eyebrows up under his hair. The rest of the young men and women who made up the choir sat on the front seats round about, and rose with the precentor. But the main body of the congregation only stood during the prayers. It was a relief to get up; yet the prayers were so long this was a doubtful blessing after all, and most of the worshippers sought some bodily support a good while before the end of the petitions. The sermon lasted a full half-hour. Its subject was "The Joys of Christ," and the preacher went through a list of firstlies and secondlies up to about tenthlies. He had a slow, droning voice, and the effort to keep awake in those hard, straight-backed seats was painful. When the possibilities of the more ordinary changes of position had been exhausted, the worshippers would lean on the pew-backs in front of them or would bow themselves forward with their elbows on their knees. Some of the men gripped their heads between their hands in a manner that suggested they were suffering severely, and a few actually slept. There were female nodders, too, and one young woman in the manse pew was several times on the point of falling over altogether. She had continually to open her eyes with a decided effort and look severely at the minister to keep from disgracing herself. We were a very forlorn congregation, when at twenty-five minutes of two, the minister finished his elucidation of the tenth of Christ's joys, and we were released. The crowd filed out into the sunshine, and straggled along the lane and roadway toward the village. Every one was on foot. Even from a distance of three or four miles the people walked, whole families together. Some of them were old ladies, with their outer skirts caught up over their arms, stepping along as vigorously as if they were in their teens instead of past threescore. The adherents of "Auld Boblin" were not as devoted to their faith as the worshippers at the other local churches, and though their numbers were decidedly greater, and in spite of their government income, they fell distinctly behind the dissenters in the support they gave their kirk and minister. The minister himself had not the character of the other pastors. His lacks were moral, not intellectual, for he was by no means a dull or ignorant man. Some very ill stories were told of him, and it was well known that both he and his wife drank at times a good deal beyond moderation, even if their red-faced heaviness had not confessed the fact.  Sunday

Afternoon

But clerical tippling is not regarded as so detrimental to a pastor's influence and efficiency in Scotland as it would be in America. The clergy of the dissenting kirks, however, are now nearly all total abstainers. The opposite is true of their fellows of the Established Kirk, and though the temperance sentiment is undoubtedly growing among them, there are those who are far from being a credit to their calling. I was told by one Scotch minister that not many years ago, in his boyhood home near Oban, they had an elderly clergyman who used to get drunk every time he went making parish calls. At each home whiskey was set forth for him, after the time-honored custom of the region, and this was so much to his liking, and the potations he drank were so liberal, that by the time he had made a half dozen visits it was necessary for some one to carry him back to the manse. The drink habit grew on him, and at length he would appear intoxicated in the pulpit, and be so maudlin the church elders would be obliged to interrupt him and take him out of the kirk by force. In the end the Presbytery induced him to resign. His habits, however, were less of a scandal than they might have been in that particular community, had not his two predecessors died of delirium tremens. No doubt this is an extreme case, but that such a thing is possible is suggestive of conditions that are a little surprising to say the least.  Church in a Northern Glen |