| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2010 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click

Here to return to

Castles and Chateaux of Old Navarre and the Basque Provinces Content Page Return to the Previous Chapter |

(HOME)

|

|

CHAPTER

XXV

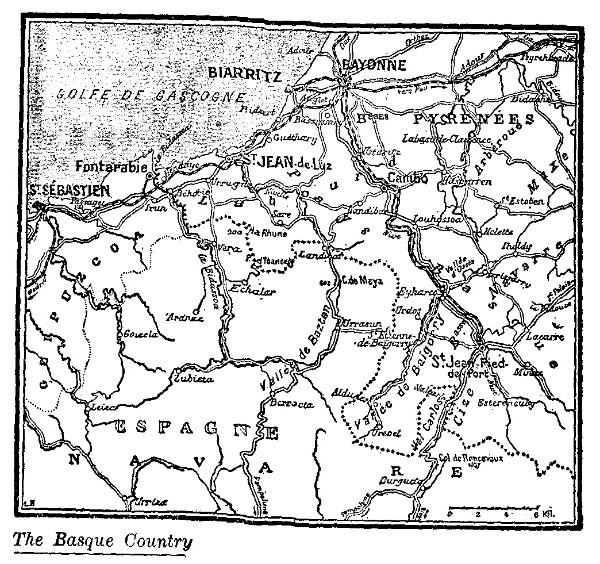

THE BASQUES  THE BASQUE COUNTRY MOST people, or certainly most women, connect the name basque with a certain article of ladies' wearing apparel. Just what its functions were, when it was in favour a generation ago, a mere man may not be supposed to know. Théophile Gautier has something to say on the subject, so he doubtless knew; and Victor Hugo delivered himself of the following couplet "C'était plaisir de voir danser la jeune fille; Sa basquine agitait ses pailettes d'azur." The French Basques are divided into three families, the Souletins, the Bas-Navarrais and the Labourdins. They possess, however, the same language and other proofs of an identical origin in the simplicity and quaintness of their dress and customs. The Labourdin Basques inhabit the plains and valleys running down to the sea at the western termination of the Pyrenees, and live a more luxurious life than the Navarrais, even emigrating largely, and entering the service of the merchant and naval marine; whereas the Navarrais occupy themselves mostly with agriculture (and incidentally are the largest meat eaters in France) and contribute their services only to the army. The contrast between the sailor and fisher folk of the coast, and the soldiers and farmers of the high valleys is remarkable, as to face and figure, if not readily distinguishable with respect to other details. The Labourdin Basques have a traditional history which is one of the most interesting and varied records of the races of western Europe. In olden times the Golfe de Gascogne was frequented by great shoals of whales, and the Basques, harpooning them and killing them in the waters of their harbours, came to control the traffic. When the whale industry fell off, and the whales themselves receded to the south seas, the Basques went after them, and for long they held the supremacy as before, finally chasing them again to the Newfoundland Banks, which indeed it is claimed the Basques discovered. At any rate the whaling industry proved a successful and profitable commerce for the Basques, and perhaps led the way for their migration in large numbers to South America and other parts of the New World. Among the Basques themselves, and perhaps among others who have given study to the subject, the claim is made that they were the real discoverers of the New World, long before Columbus sighted the western isles. Thus is the Columbus legend, and that of Leif, son of Eric, shattered by the traditions of a people whom most European travellers from overseas hardly know of as existing. It seems that a Spanish Basque, when on a voyage from Bayonne to Madeira, was thrown out of his course and at the mercy of the winds and waves, and finally, after many weeks, landed on the coast of Hayti. Columbus is thus proved a plagiarist. The Basques as a race, both in France and in Spain, are a proud, jovial people, not in the least sullen, but as exclusive as turtle-doves. Unlike most of the peasants of Europe, whether at work or play, they march with head high, and beyond a grave little bow, scarcely, if ever, accost the stranger with that graciousness of manner which is usually customary with the farmer folk of even the most remote regions in France, those of the Cevennes or the upper valleys of Dauphiné or Savoie. Upon acquaintance and recognition of equality, the Basques become effusive and are undoubtedly sincere. They don't adopt the mood for business purposes as does the Norman or the Niçois. The traditions of the Basques concerning their ancestors comport exactly with their regard for themselves, and their pride of place is noticeable to every stranger who goes among them. They believe that they were always an independent people among surrounding nations of slaves, and, since it is doubtful if the Romans ever conquered them as they did the other races of Gaul, this may be so. The very suggestion of this superior ancestry accounts for many of their manners and customs. Full to overflowing with the realization of their "noblesse collective," they have an utter contempt for an individual nobility that borders close upon radicalism and republicanism. The greatest peer among them is the oldest of the house (eteheco-sémia) and he, or she, is the only individual to whom is paid a voluntary homage. Like the children of Abraham, the Basques are, away from the seacoast, for the most part tenders of flocks and herds, and never does one meet a Basque in the mountains or on the highroads but what he finds him carrying a baton or a goad-stick, as if he were a Maréchal de France in embryo. It is their "compagnon de voyage et de fête," and can on occasion, when wielded with a sort of Jiu-Jitsu proficiency, be a terrible weapon. As many heads must have been cracked by the baton of the Basque, as by the shillelagh of the Irishman, always making allowance for the fact that the Basque is less quarrelsome and peppery than Pat. There is absolutely no question but that the Basques are hospitable when occasion arises, and this in spite of their aloofness. In this respect they are like the Arabs of the desert. And also like the Hebrews, the Basques are very jealous of their nationality, and have a strong repugnance against alliances and marriages with strangers. The activity and the agility of the Basques is proverbial, in fact a proverb has grown out of it. "Leger comme un Basque," is a saying known all over France. The Basque loves games and dances of all sorts, and he "makes the fête" with an agility and a passion not known of any other people to a more noticeable extent. A fête to the Basque, be it local or national, is not a thing to be lightly put aside. He makes a business of it, and expects every one else to do the same. There is no room for onlookers, and if a tourney at pelota — now become the new sport of Paris — is on, it is not the real thing at all unless all have a hand in it in turn. There are other pelota tourneys got up at Biarritz, Bayonne and Feuntarrabia for strangers, but the mountain Basque has contempt for both the players and the audience. What he would think of a sixty or eighty thousand crowd at a football or a cricket game is too horrible for words. Pelota Basque has its home in the Basque country, both in the French and Spanish provinces, and the finest players of pelota come from here. Pelota Basque is played in various parts of Spain, as well as pelota which is played with the three walls and the open hand, and thus the two games are found in the same country at the same time, though differing to no small extent. It is to be regretted that there is not more literature connected with the game. The history of ball games is always interesting, and pelota is without doubt worthy of almost as much research as has been expended on the history of tennis. In Spain pelota is largely played at San Sebastian, Bilbao, Madrid, Barcelona. There are three walls, and the game is played by four players, two on each side. Before the three-wall game was ever thought of, Pelota Basque was played in the principal cities of the Basque country, and it is still played on one wall in such cities as St. Jean-de-Luz, Biarritz, Cambo, Dax, Mauléon, Bordeaux, and even at Paris, and is recognized as the superior variety. This was explained over the signatures of a group of professional players who introduced the game to Paris as follows: "We, the pelotarie playing here, can play either on frontones of the Spanish or Basque form; but there is no doubt that the latter is the better game, and we feel we must state that the measures of the court, and the wall, and its top curves are the same in the Paris fronton as at St. Jean-de-Luz, which is considered by all authorities an ideal court. Here we play three against three, and all the 'aficionados' who have witnessed a game of Basque pelota are unanimous in saying it is a sport of a high grade, although different from the three-wall game. "We, the undersigned, are the recognized champions of pelota Basque. "ELOY, of the Barcelona's Fronton. "MELCHIOR, of San Sebastian's Fronton. "VELASCO, of Biarritz and Bilbao's Fronton. "LEON DIHARCE, of Paris and Buenos Ayres Fronton." It is by the word euskualdunac that the Basques are known among themselves. Their speech has an extraordinary sound, the vowels jumping out from between the consonants as a nut shell crushes in a casse-noisette. No tongue of Europe sounds more strange to foreign ears, not even Hungarian. On the other hand a Basque will speak French perfectly, without the slightest accent, when he feels like it, but his Béarnais neighbour makes a horrible mess of it, mixing Parisian French with his chattering patois. What a language and what a people the Basques are, to be sure! Some day some one will study them profoundly and tell us much about them that at present we only suspect. This much we know, they are allied to no other race in Europe. Perhaps the Basques were originally Arabs. Who knows? A young Basque woman who carries a water-jug on her head, and marches along with a subtle undulation of the hips that one usually sees only in a desert Arab or a Corsican girl, certainly is the peer of any of the northern Europeans when it comes to a ravishing grace and carriage. It is the Pays Basque which is the real frontier of France and Spain, and yet it resembles neither the country to the north nor south, but stands apart, an exotic thing quite impossible to place in comparison with anything else; and this is equally true of the men and women and their manners and customs; the country, even, is wild and savage, but gay and lively withal. One may not speak of two peoples here. It is an error, a heresy. On one side, as on the other, it is the same race, the same tongue, the same peoples — in the Basses-Pyrenees of modern France as in the Provinces of Guipuzcoa, Navarre and Biscaye of modern Spain. The only difference is that in France the peasant's béret is blue, while in Spain it is red. The antiquity of la langue escuara or eskualdunac is beyond question, but it is doubtful if it was the speech of Adam and Eve in their terrestrial paradise, as all genuine and patriotic Basques have no hesitancy in claiming. At a Geographical Congress held in London in 1895 a M. L. d'Abartiague claimed relationship between the Basques of antiquity and the aborigines of the North American continent. This may be far-fetched or not, but at any rate it's not so far-flung as the line of reasoning which makes out Adam and Eve as being the exclusive ancestors of the Basques, and the rest of us all descended from them. Curiously enough the Spanish Basques change their mother-tongue in favour of Castilian more readily than those on the other side of the Bidassoa do for French. The Spanish Basques to-day number perhaps three hundred and fifty thousand, though included in fiscal returns as Castilians, while in France the Basques number not more than one hundred and twenty thousand. There are two hundred thousand Basques in Central and South America, mostly emigrants from France. The Basque language is reckoned among the tongues apportioned to Gaul by the geographer Balbi; the Greco-Latine, the Germanic, the Celtic, the Semitic, and the Basque; thus beyond question the Basque tongue is a thing apart from any other of the tongues of Europe, as indeed are the people. The speech of the Basque country is first of all a langue, not a corrupted, mixed-up patois. Authorities have ascribed it as coming from the Phoenician, which, since it was the speech of Cadmus, the inventor of the alphabet, was doubtless the parent of many tongues. The educated Basques consider their "tongue" as one much advanced, that is, a veritable tongue, having nothing in common with the other tongues of Europe, ancient or modern, and accordingly to be regarded as one of the mother-tongues from which others have descended. It bears a curious resemblance to Hebrew, in that nearly all appellatives express the qualities and properties of those things to which they are applied. From the point of grammatical construction, there is but one declension and conjugation, and an abundance of prepositions which makes the spoken speech concise and rapid. Basque verbs, moreover, possess a "familiar" singular and a "respectful" singular — if one may so mark the distinction, and they furthermore have a slight variation according to the age and sex of the person who speaks as well as with regard to the one spoken to. Really, it beats Esperanto for simplicity, and the Basque tongue allows one to make words of indeterminate length, as does the German. It is all things to all men apparently. Ardanzesaroyareniturricoborua, one single word, means simply: "the source of the fountain on the vineyard-covered mountain." Its simplicity may be readily understood from the following application. The Basque "of Bayonne" is Bayona; "from Bayonne," Bayonaco; that "of Bayonne," Bayonacoa. The ancient and prolific Basque tongue possesses a literature, but for all that, there has never yet been discovered one sole public contract, charter or law written in the language. It was never the official speech of any portion of the country, nor of the palace, nor was it employed in the courts. The laws or fueros were written arbitrarily in Latin, Spanish, French and Béarnais, but never in Basque. The costume of the Basque peasant is more coquettish and more elegant than that of any other of the races of the Midi, and in some respects is almost as theatrical as that of the Breton. All over Europe the characteristic costumes are changing, and where they are kept very much to the fore, as in Switzerland, Tyrol and in parts of Brittany, it is often for business purposes, just as the yodlers of the Alps mostly yodel for business purposes. The Basque sticks to his costume, a blending of Spanish and something unknown. He, or she, in the Basque provinces knows or cares little as to what may be the latest style at Paris, and bowler hats and jupes tailleurs have not yet arrived in the Basque countryside. One has to go into Biarritz or Pau and look for them on strangers. For the Basque a béret bleu (or red), a short red jacket, white vest, and white or black velvet corduroy breeches are en régie, besides which there are usually white stockings, held at the knees by a more or less fanciful garter. On his feet are a rough hob-nailed shoe, or the very reverse, a sort of a moccasin made of corded flax. A silk handkerchief encircles the neck, as with most southern races, and hangs down over the shoulders in what the wearer thinks is an engaging manner. On the days of the great fêtes there is something more gorgeous still, a sort of a draped cloak, often parti-coloured, primarily the possession of married men, but affected by the young when they try to be "sporty." The tambour de Basque, or drum, is a poor one-sided affair, all top and no bottom; virtually it is a tambourine, and not a dram at all. One sees it all over the Basque country, and it is as often played on with the closed fists as with a drumstick. Like most of the old provincials of France, the Basques have numerous folk-songs and legends in verse. Most frequently they are in praise of women, and the Basque women deserve the best that can be said of them. The following as a sample, done into French, and no one can say the sentiment is not a good deal more healthy than that of Isaac Watts's "hymns." "Peu

de femmes bonnes sont bonnes danseuses,

Bonne danseuse, mauvaise fileuse; Mauvaise fileuse, bonne buveuse, Des femmes semblables Sont bonnes à traiter à coups de baton." In the Basque country, as in Brittany, the clergy have a great influence over the daily life of the people. The Basques are not as fanatically devout as the Bretons, but nevertheless they look to the curé to explain away many things that they do not understand themselves; and let it be said the Basque curé does his duty as a leader of opinion for the good of one and all, mach better than does the country squire in England who occupies a somewhat analagous position. It is through the church that the Euskarian population of the Basses-Pyrenees have one of their strongest ties with traditional antiquity. The curés and the communicants of his parish are usually of one race. There is a real community of ideas. As for the education of the new generation of Basques, it is keeping pace with that of the other inhabitants of France, though in times past even rudimentary education was far behind, and from the peasant class of only a generation. or so ago, out of four thousand drawn for service in the army, nearly three hundred were destitute of the knowledge of how to read and write. In ten years, however, this percentage has been reduced one half. The emigration of the Basques has ever been a serious thing for the prosperity of the region. Thirteen hundred emigrated from the "Basque Française" (for South and Central America) and fifteen hundred from the "Basque Espagnole." In figures this emigration has been considerably reduced of late, but the average per year for the last fifty years has been (from the Basse-Pyrenees Département alone) something like seventeen hundred. The real, simon-pure Basque is seen at his best at Saint Jean-Pied-de-Port, the ancient capital of French Navarre. "Urtun hiriti urrumofagariti," say the inhabitants: "Far from the city, far from health." This isn't according to the doctors, but let that pass. To know the best and most typical parts of the Basque country, one should make the journey from Saint Jean-Pied-de-Port to Mauléon and Tardets. Here things are as little changed from mediævalism as one will find in modern France. One passes from the valley of the Nive into the valley of the Bidouze. There are no railways and one must go by road. The road is excellent moreover, though the distance is not great. Here is where the automobilist scores, but if one wants to take a still further step back into the past he may make the forty kilomètres by diligence. This is a real treat too, not at all to be despised as a means of travel, but one must hurry up or the three franc diligence will be supplanted by a "light railway," and then where will mediævalism come in. All the same, if you've got a feverish automobile panting outside St. Jean's city gate, jump in. There are numerous little villages en route which will not detain one except for their quaintness. One passes innumerable oxen, all swathed in swaddling clothes to keep off the flies and plodding slowly but surely along over their work. A train of Spanish mules or smaller donkeys pulling a long wagon of wood or wool is another common sight; or a man or a woman, or both, on the back of a little donkey will be no novelty either. This travel off the beaten track, if there is not much of note to stop one, is delightful, and here one gets it at its best. Stop anywhere along the road at some inn of little pretence and you will fare well for your déjeuner. It will be very homely, this little Basque inn, but strangers will do very well for their simple wants. All one does is to ask "Avez-vous des oeufs? Avez-vous du jambon? Du vin, je vous prie!" and the smiling rosy-cheeked patronne, whose name is Jeanne, Jeannette, Jeanneton, Jeannot or Margot — one or the other it's bound to be — does the rest with a cackling "Ha! he! Eh ben! eh ben!" And you will think you never ate such excellent ham and eggs in your life as this Bayonne ham and the eggs from Basque chickens — and the wine and the home-made bread. It's all very simple, but an Escoffier could not do it better. The peasant's work in the fields in the Basque . country may not be on the most approved lines, and you can't grow every sort of a crop here in this rusty red soil, but there is a vast activity and an abundance of return for the hard workers, and all the Basques are that. The plough is as primitive as that with which the Egyptian fellah turns up the alluvial soil of the Nile, but the Basque makes good headway nevertheless, and can turn as straight a furrow, up the side of a hill or down, as most of his brothers can on the level. In the church at Bunus is a special door reserved in times past for the descendants of the Arabs who had adopted Christianity. Here in the Basque country you may see the peasants on a fête day dance the fandango with all the ardour and the fervour of the Andalusians themselves. Besides the fandango, there is the "saute basque," a sort of a hop-skip-and-a-jump which they think is dancing, but which isn't the thing at all, unless a grasshopper can be said to dance. "Le Chevalet" is another Basque dance whose very name explains itself; and then there is the "Tcherero," a minuet-sort of a dance, wholly by men, and very graceful and picturesque it is, not at all boisterous. The peasants play the pastoral here as they do in Languedoc and Provence, with good geniuses and evil geniuses, and all the machinery that Isaac Watts put into his hymns for little children. Here the grown men and women take them quite as seriously as did the children of our nursery days. In the Basses-Pyrénées, besides the Basques, is distinguishable another race of dark-skinned, under-sized little men, almost of the Japanese type, except that their features are more regular and delicate. They are descendants of the Saracen hordes which overran most of southern Gaul, and here and there found a foothold and left a race of descendants to tell the story. The Saracens of the Basque country were not warlike invaders, but peaceful ones who here took root, and to-day are known as Agotacs-Cascarotacs. It is not difficult to distinguish traces of African blood among them, just the least suspicion, and they have certain religious rites and customs — seemingly pagan — which have nothing in common with either the Basques or the French. They are commonly considered as pariahs by other dwellers roundabout, but they have a certain individuality which would seem to preclude this. They are more like the "holy men" of India, than they are like mere alms beggars, and they have been known to occupy themselves more or less rudely with rough labour and agricultural pursuits. They have their own places in the churches, those who have not actually died off, for their numbers are growing less from day to day. It can be said, however, that — save the cagots and cretins — they are the least desirable and most unlikable people to be found in France to-day. They are not loathsome, like lepers or cretins or goitreux, but they are shunned by all mankind, and for the most part remain well hidden in obscure corners and culs-de-sac of the valleys away from the highroads. The Spanish gypsies are numerous here in the Basque country, as might be expected. They do not differ greatly from the accepted gypsy type, but their marriage customs are curious. As a local authority on gypsy lore has put it: "an old pot serves as a curé and notary — u bieilh toupi qu'ous sert de curé de nontari." The marriageable couple, their parents and their friends, assemble in a wood, without priest or lawyer, or any ceremony which resembles an official or religious act. An earthenware pot is thrown in the air and the broken pieces, as it tumbles to the ground, are counted. The number of pieces indicate the duration of the partnership in years, each fragment counting for a year. Simple, isn't it! |