| Web

and Book

design, |

Click

Here to return to |

|

CHAPTER 1 THE BEAVERS OF NORTH AMERICA. THEIR HABITS OF LIFE AND THEIR WONDERFUL ENGINEERING FEATS IN a quiet pond, far away in the wilds of Canada, a small, dark object appeared silently and without disturbing the serenity of the placid waters. A few minutes later, the small object moved slowly along, and lengthening quivering lines made the inverted images of the opposite trees tremble in the reflected sunset so that the dark greens of the firs and rich reds and yellows of the birches and maples danced together in the ripples. The dark object was a beaver and he was filled with the fear of man, inherited through a long line of ancestors who had striven to outwit those that sought their destruction. This survivor of a much persecuted race had sought the far away country with the hope of being able to live with his family unmolested by the constant dread of the steel trap. Unlimited care and constant watchfulness were the price he must be always ready to pay for his safety. And even so the chances were entirely against him. Not until the sun had set, and the sky was lighted by the glorious afterglow, had he ventured to leave the protection of his well-built house. A long swim under water brought him to the middle of the pond which he and his family had made. From this point he could inspect the encircling hillsides, and the friendly currents of air would perhaps carry to his keen nose the scent of any human enemy who might be lurking in the neighbourhood. Apparently the evening breeze was untainted by man-scent. But the beaver considered it wise to make still more sure, so he swam a short distance, and then disappeared beneath the water so softly that scarcely a ripple marked the place where he had dived. A few minutes later, he quietly reappeared close to the shore on the lee side of the pond. Once more he remained as still as a floating log, his nose pointed toward the almost imperceptible breeze, his dark rounded ears raised to catch the slightest sound. Then slowly and silently he swam round the pond closely following the irregular shore line. No sign of danger could he find. Evidently no stranger had come near his home since he had entered his house that morning. So when he came to where the water was very shallow he cut off a small willow branch and proceeded to nibble the bark for his supper. In the stillness of the evening the grating sound of his sharp teeth cutting through the bark sounded loudly. His family in the lodge at the further end of the pond heard it and knew that they could come forth with safety. Three small heads soon appeared on the surface of the water near the house and soon another and larger one. She was the mother of the three, and she was satisfied that her husband had sufficiently well examined the immediate vicinity. So without wasting time she and her youngsters proceeded each to their particular choice of shrub or tree and ate what they wanted.

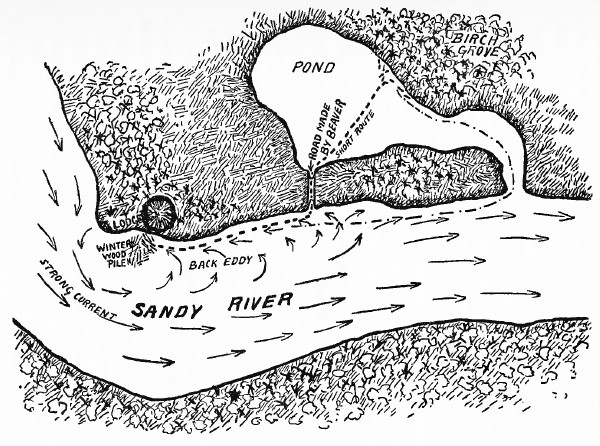

It was in the month of October, the busiest month in the beavers’ year. The cold nights warned them of the approaching winter. The glistening white frost which covered the grass each night with its myriad crystals and the thin sheets of “window-pane” ice which bordered the pond were the forerunners of the cold that would come later. The terrible, relentless cold which held all that northern country in its icy embrace, which made the ponds resemble solid land and subdued the most turbulent streams by converting them into irregular masses of snow-covered ice; the cold which so often for months at a time held the beavers prisoners in their houses, free only to roam in the pond beneath the shadow of the impenetrable ice; the pitiless cold which spreads famine among the dwellers of the northern woods so that hunger-bred courage, and the cunning persistence which comes from necessity, renders the wolves and gluttons a source of danger to all beavers, especially to those who are not well-housed. Therefore, in October or even earlier, the beavers must work diligently and make use of the extraordinary intelligence which they have developed through the thousands of years since they became as we know them to-day. The beavers we have been watching in the little far-away pond spent but a short time over their afternoon tea. The time for enjoyment and ease had passed, and they must get to work. The dam had to be finished. The house needed its outside coating of mud and there was still a large amount of wood to be cut for the winter supply. Altogether an appalling lot to be done in the short time that remained before winter; and so the little animals left their partly-peeled twigs and each went to do that which he considered most necessary for the welfare of the family. The father first made a careful inspection of the dam and found many places which were in need of additional material. This he procured from the bottom of the pond, bringing up big sods of earth and partly decayed grass which he carried in his hands, under his chin. As these were brought to the dam he pushed them into position, arranging every piece so that the structure was level and fairly smooth. Here and there a stick or short log was deemed necessary; some of these he found on the water’s edge, others on the shore. The mother beaver in the meantime was busily engaged in improving the house. This needed more sticks and the weak places had to be filled in with sod and mud. The young assisted in this work, each bringing his small load and arranging it as he had seen his parents do. Occasionally, the family stopped work altogether and took time to nibble a little bark from some particularly tempting branch. Then a very important work demanded attention. The cutting of trees and gathering of the winter supply of food. On this must depend their safety during the cold weather. A few days ago, they had felled a large birch tree which had dropped on the edge of the pond. Already they had cut off many of the most accessible branches and now they continued the work of stripping the trunk of its limbs. Some were so large that it was necessary to cut them into several sections, their length depending on the thickness. As each piece was cut through with their keen-edged teeth, it was floated across the water to the pile near the house. In swimming, the beaver held the branch with his teeth, and on arriving at the food pile, he would take a fresh grip with his teeth and dive down carrying the branch with him. Then the whole pile would tremble slightly as he forced the piece into the tangled mass of sticks, well below the surface of the water. Trip after trip was made in this manner, each trip adding its mite to the great supply of winter food, and while the young were thus engaged one of the old ones was up in the woods searching for a fresh tree to cut down. Many things had to be considered in the selection of a suitable tree. It must be in a, place where it could be easily cut, and not too far from the water. Then it should be clear of other trees so that it would fall — unfortunately they often make mistakes in this respect — and finally what is of great importance, the tree must be in the right condition. That could only be ascertained by cutting into the bark, and as he went about he marked several trees in this way before finding one that suited his fastidious taste. Then, sitting on his hind legs, with his large, heavy tail as a balance, he commenced the hard work of biting through the tough wood, after first eating the coating of bark. The noise made by his sharp teeth tearing out the great chips sounded loud in the still evening. Crunch, crunch, crunch, crunch, then a pause as he dropped the clean cut chips; and again the crunching resounded through the darkening woods. For half an hour this continued. Then as a beaver does not like to work too long on any one task, he shuffled off, leaving the birch tree with its gaping wound gleaming white against the sombre back ground. There was a road to make from where that tree would fall, down to the pond, so the beaver attended to that, combining pleasure with his labours, for as he found small saplings of hazel or mountain ash growing in the line of the path, he cut them down and ate off some of the bark.

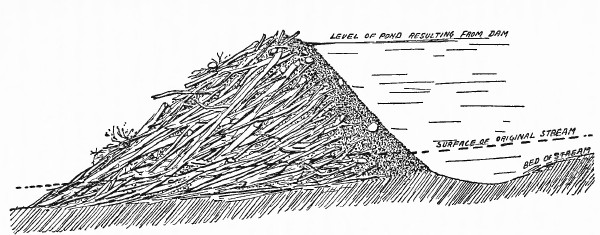

Others he carried down to the water and swam with them to the harvest pile. Nothing must be wasted. Every shrub or sapling which obstructed the way had to be cut down; if it was not good enough for food it could at least be used in the construction of house or dam. And the beaver continued his work as though he fully realised the importance of doing it well and thoroughly. Occasionally, he was joined by the other members of his family, and the big yellow full moon rising above the tree tops watched the industrious little animals as it had watched their predecessors for thousands of years. With each generation the same work had been carried on with the same persistence, the same regularity and in the same way. The only visible change was that in former years, before man had begun the work of destroying the harmless creatures, and which, since the arrival of the white people of the eastern world, had been so ruthlessly carried on, the beavers did their wood-cutting and dam-building almost as much by daylight as by the light of the stars and moon.1 But the little fur-bearers had learned gradually that the sun was not their friend; it offered them no protection from the deadly persecutions of their two-footed enemies, and so they had come to work only under the friendly cover of darkness, or by the soft light of the moon and the twinkling of the stars. Even then, they were always nervously alert, each sound must be understood before it could be ignored. A falling leaf floating almost noiselessly to earth would cause them to desist in their labours, for though they knew full well that during the autumn the leaves, having fulfilled their duties, bid farewell to the slender branches, yet their falling might mean the stealthy approach of a man who, touching the tree as he passes, shakes down the dying leaves. The noiseless tread of the deer as it carefully made its way over the velvet carpet of moss they knew, and as it meant no harm, they seldom took notice of it. No man walked liked that. Even the moccasined foot of the Indian made more sound, and set up a vibration on the earth’s surface which in no way resembled the delicate footfall of the wild animals. But their enemies, the powerful wolverines, the padded-footed lynx, and the hungry, clever, keen-witted wolf could approach without sound or warning save the scent which they could not disguise. Therefore, when the beaver worked, his mind was divided, and he stopped at frequent intervals to listen, and to test the air for signals of danger, and at the slightest warning he would make his way to the water which offered a safe retreat from nearly all of his enemies. If the danger was imminent, he and all his family could seek safety in the house, and remain there perhaps for the rest of the night, coming out only under water to take some twigs into the house where they could enjoy a meal without fear of pursuit. But the night passed without mishap, and the first gleam of dawn saw them still busily engaged in their various tasks, hidden from view by the mist which nearly always settles on the ponds during the cool nights. As the rising sun cleared the air, the beavers, tired after the long night’s work, retired to their house, all holding an animated conversation as though discussing the work they had accomplished. Gradually the puppy-like voices died away before the morning breeze disturbed the surface of the pond, and they slept the sleep of those who have worked hard and well, and earned their rest. Let us leave them there to dream of the days when the steel trap will be a thing of the past and they will be able to continue the work which Nature intended they should do. We have had a glimpse of them in their far-away home and have seen a typical night’s employment. Perhaps the question comes to us, Why do they have to work so hard? Most of the wild animals live a life of comparative ease, thinking only of the day and making no plans, no provision for the morrow. Their food is gathered as it is needed, and most of them have their homes where they happen to be. When tired they seek a sheltered spot and go to sleep, and beyond watching for danger, they trouble themselves but little. But the beaver has definite ideas of what is necessary for his welfare. He plans months ahead. He undertakes stupendous tasks — tasks which demand skill of no mean order. Indeed, some of the most important work done by them may seem at first glance to be superfluous. Why, for instance, does he build dams when water is abundant nearly everywhere within his natural range? Let us, therefore, examine the work and see how it serves a very definite purpose, and having done that we will follow the beaver throughout a few years of their lives and see how they live and how thoroughly their various undertakings work out in the best possible way. The most conspicuous work, so far as visible results are concerned, is the dam; and the purpose it serves is not so much to make a swimming pool, as some people imagine, as to keep a body of water at a more or less constant level in order to ensure certain ends: (1) to conceal the entrances to the houses and so prevent the entrance of any land enemies, (2) to be a place for the safe storage of wood for food during the winter, (3) to render the transporting of this wood as simple as possible, and (4) to be a place of retreat in case of attack. To better appreciate the value of the dam it is necessary to understand the structure of the houses, for there are several types. The most primitive is simply a hole in a bank, with no surface work. This represents what is probably the original and primitive form of house. The entrances, for there are usually more than one, are well below the surface of the water. Then we have the next step in advancement: the hole in the bank with the living chamber coming to the surface, so that in order to make it more secure against marauders and render it drier, a roughly arranged pile of brush, sticks, logs, and mud and grass is heaped over it. From this it is but a step to the house which is entirely above ground, and placed either on the bank or on an island, and then the final development in which the beavers make the island as a foundation.

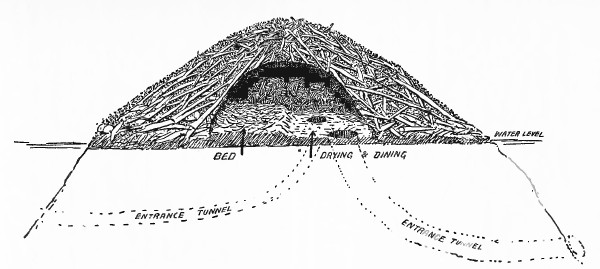

In appearance, the two latter types are identical and both have the entrances beneath the water. In building these houses or lodges, as they are more commonly called, the beginning is a composition of mud, brush and small sticks, from which the bark is nearly always eaten. Whether the mound is placed over the opening of the burrow, or whether the burrow is made after the house has been started, I cannot say with absolute certainty, but from what I have observed of the beginnings of lodges, there seems every reason to believe that the burrow precedes the lodge. Gradually, as the mound becomes large enough, the inside is hollowed out, then more and more material is added to the outside, larger sticks and even poles or logs are used, all more or less pointing to the apex, so that they support each other to some extent. Water-soaked grass, roots and mud are employed to fill in the openings, with the result of making the whole structure nearly light-tight and practically water-tight. As soon as the nights are cold enough to freeze, the surface is plastered over with several inches of mud which is usually gathered from the pond or river bottom. This fact, has, I know been questioned even by such authorities as Thompson Seton, who in his excellent book2 says: “It (the beaver) never plasters the lodge with mud outside. All lodges are finished outside with sticks.” This is more or less true during the earlier part of the season, but in most cases which have come under my observation the houses were thickly plastered over immediately before the actual coming of winter.”3 The mud, of course, freezes into a solid and intensely hard protective coating — so hard that even the wolves cannot tear a way through; but it breaks away early in the spring when softened by the thaw, and the heavy rains wash it off, leaving the outside an untidy mound of sticks and poles. In evidence of this I have made photographs both in Newfoundland and Canada. Some of the houses found in the former country were made almost entirely of mud, sod, and grass, with only a few sticks used in the centre, probably with the idea of leaving the almost inevitable ventilation flue. The form of the lodges varies greatly and it is impossible to lay down any hard and fast rules. Several times I have found houses built surrounding a tree, either living or dead. In such cases the ventilation is afforded by the tree, as the earth and sticks do not adhere very closely to the rough bark. The very idea of making provisions for ventilation is one of the many exhibitions of the clever animals’ thoughtfulness. The existence of these ventilation flues has some times been questioned, but it has been more or less clearly shown in all of the many scores of lodges which I have examined. It is even more notice able in the winter, when the lodge appears as a mound of snow, a mound like many other irregularities in the landscape except that the snow is usually melted or partly melted at the highest point, and on very cold days a thin misty vapour may be seen rising from the place where the flue would naturally be situated. This tell-tale sign is a frequent cause of disaster for the beaver, as it reveals the presence of the lodge to the keen-eyed trapper, who naturally does not hesitate to take the fullest advantage of the information. Mr. Enos Mills in his delightful book, “In Beaver World,” which deals more particularly with the Western States, fully corroborates the fact of the existence of the ventilating flue. He says, “But little earthy matter is used in the tip-top of the house where the minute disjointed airholes between the interlaced poles give the room scanty ventilation.” We are of course faced with the question, does the beaver do this intentionally with the realization of what it means? Why not? What reasonable excuse can we have for doubting his understanding of what he is doing. But we must leave this till later when the subject of the intelligence or instinct of the beaver will be treated more thoroughly. At present, the lodge is occupying our attention. Much has been written about these examples of primitive architecture and ridiculous statements have frequently been made. Pictures have appeared (as recently as towards the end of the eighteenth century) which show the houses with two stories, and with windows and doors cut square. It will not need much intelligence to see the absurdity of these “facts.” First of all, such openings would leave the inmates entirely at the mercy of any passing enemy, and secondly, animals avoid rectangular forms. So the square apertures would be practical impossibilities. One of the earliest sane descriptions which I have been able to find of a beaver’s house appears in the Relations of the Jesuits in Canada. Father Joseph Jouvency, S. J., writes (between the years 1610 and 1613): “They locate them (the houses) on the banks of lakes and rivers; they build walls of logs, placing between them wet and sticky sods in the place of mortar, so that the work can, even with great violence, scarcely be torn apart and destroyed. The entire house is divided into several stories.4 (Levels would probably be a better word); the lowest is composed of thicker crossbeams, with branches strewn upon them, and provided with a hole or small door through which they can pass into the river whenever they wish; this story extends somewhat above the water of the river, while the others rise higher, into which they retire if the swelling stream submerges the lowest floor. They sleep in one of the upper stories; a soft bed is furnished by dry sea-weed,5 and the moss with which they protect themselves from the cold; on another floor they have their store-room and food provided for winter. The building is covered with a dome-shaped roof. Thus they pass the winter, for in summer they enjoy the shady coolness upon the shores or escape the summer heat by plunging into the water. Often a great colony of many members is lodged in one house. But, if they be incommoded by the narrowness of the place, the younger ones depart of their own accord and construct houses for themselves.” Allowing for slight inaccuracies due to translation, this is a remarkably accurate description and shows what careful observers were those sturdy, self-sacrificing priests who did so much for Canada in her early development. It is all the more extraordinary when we consider how natural history subjects were treated in those days. The inside of a beaver’s lodge is simplicity itself. There is only one chamber, unless possibly two lodges being built adjoining one another may have the rooms connecting. However, this is a condition I have never seen. The size varies, according to conditions, some being as much as twelve feet or more in diameter,6 but an ordinary house built to accommodate a family of six would have a room about four or five feet long and rather less in width, with the ceiling at the highest point a little over two feet. The ceiling is fairly smooth, all projecting sticks and roots being carefully cut off. There is, indeed, every evidence to show that the interior is really made and finished after the wall or the mound has been more or less completed. The fact that the sticks are so thoroughly interlaced accounts for the strength of the whole structure, which is arched over with a perfect network, so that when in perfect condition it will bear the combined weight of as many men as could find foothold on it. Even an old lodge may be torn apart so that only a thin shell of the woodwork remains, and yet it will readily bear the weight of a man. In very exceptional cases the domed roof will have a central support built up from the floor, and it is this support which has probably given rise to the stories of many-roomed lodges, for the support is not necessarily a smooth circular column of mud and sticks, but may be an irregular mass which, being added to from time to time, eventually becomes a sort of wall or even a complete partition with one or more openings to allow of communication. In confirmation of this explanation, there is the following description by Samuel Hearne written between the years 1769 and 1772: “Those who have undertaken to describe the inside of beaver houses, as having several apartments appropriated to various uses, such as eating, sleeping, store houses for provisions, and one for their natural occasions, etc., must have been very little acquainted with the subject.” ... “Many years constant residence among the Indians, during which I had an opportunity of seeing several hundreds of these houses, has enabled me to affirm that everything of the kind is entirely void of truth.” ... “It frequently happens, that some of the large houses are found to have one or more partitions, if they deserve that appellation; but that is no more than a part of the main building, left by the sagacity of the beaver to support the roof. On such occasions, it is common for those different apartments, as some are pleased to call them, to have no communication with each other but by water; so that in fact they may be called double or treble houses, rather than different apartments of the same house. I have seen a large beaver house built in a small island, that had near a dozen apartments under one roof; and, two or three of these only excepted, none of them had any communication with each other but by water. As there were beaver enough to inhabit each apartment it is more than probable that each family knew its own, and always entered at their own door.” He goes on to say that his Indians took thirty-seven beavers out of this house, while many others escaped. It is very doubtful whether houses of this type exist at the present day, nor indeed for many years past. The ground floor or lowest level is only three or four inches above the surface of the water. This is used as the “dining-room” and for drying their coats. About half of the space is thus occupied, the other half is raised six or eight inches, and is the sleeping apartment. It is well covered with bedding made of dry grass, which is cut while growing, or with shredded wood, the latter being more frequently employed. In cutting this bedding, the beaver tears the wood into long strips as shown in the accompanying illustration. Whether or not moss is used, I cannot tell, but in the more eastern portion of the beavers’ range, I have never seen any in the lodges, nor have I seen the slightest evidence of its being gathered from the ground or trees. However, Mills say that “A few beds are made of grass, leaves, or moss from the ground or trees.”

Occasionally, houses of immense size are found, the largest I have actually measured was in Newfoundland, on the banks of Sandy River. It was thirty-seven feet in its greatest diameter and seven feet in outside height. For about six years it had been the home of a colony of beavers, nine members or perhaps more having occupied it at one time. Lodges of this size are extremely rare, and I can find no record of any that were as large. What size the chamber was can only be conjectured, as I did not feel justified in breaking into the structure, much as I wished to see the interior. In the floor of the lodges are the entrances, there being usually two, but sometimes three or even more, their common size varying from ten to about twenty-five inches in diameter. The idea of having more than one is probably to allow of escape in case of some enemy finding its way in through one of the burrows. It also permits of different members coming in and going out at the same time, as the tunnels are scarcely large enough for the animals to pass each other. Where these tunnels enter the pond, they are more or less arched over with a network of sticks, evidently put there to prevent the burrow falling in. In some instances there is quite a long passage-way cut through a compressed, tangled mass of brush, which was probably originally the remains of a winter food pile. In planning these entrances to the lodge, it is clearly shown that the beaver know what they are about and make provision for their needs with great thoroughness. No sharp bends are made, for that would make it difficult if not impossible, to carry in the sticks which they take into the house to feed on. After all the bark is eaten the bare stick is taken out to be used in the future for building and repairing lodges and dams. Some very small twigs when peeled are worked into the earth for flooring in order to allow for the wear and tear, and keep the floor as dry as possible.

Cleanliness is of course essential where so many animals are confined in such restricted quarters. The beaver are model housekeepers and they allow no dirt or rubbish to accumulate. Everything is neat and tidy, whether the number of inmates is small or large. How they manage to keep it as dry as they do is a marvel when one considers that each time a beaver goes into the lodge he must be wet, as his only entrance is through the water. It is obvious therefore that on emerging from the water they must dry themselves off very thoroughly before going near their beds or nests. The fact of their making these beds on a higher level shows that they use their intelligence and under stand that water does not run uphill. If the bedding should get wet frequently it would be but a short time before it decayed, especially as there is not a superabundance of air in the houses. Fortunately the beaver has low respiration and consequently needs very little ventilation in his home. On this account he can keep warm, and even during the cold winter weather, when the temperature of the outside air is perhaps thirty or forty degrees below zero, the animal heat generated by the beaver is sufficient to keep the house comfortable. This warmth and the lack of light and air has the disadvantage of causing troublesome parasites to thrive, much to the annoyance of the thickly-furred animals, and probably accounts for their so frequently using shredded wood for bedding. Softer material could be found, but it is doubtful whether it would be sanitary. The size of the material used on the outside of the lodges is most variable. As already stated, in some instances no sticks of appreciable size are to be found on the lodges. Then, again, regular logs or heavy poles are seen on the lodges. But logs or poles (whichever you like to call them, and it is hard to say where one begins and the other ends) of eighteen feet in length and about six inches in diameter at the larger end are frequently used, and shorter pieces of from one foot in length upwards and having a diameter of eight or nine inches are not uncommon. Just what purpose these short and very heavy pieces serve is difficult to say. They certainly add weight, but is that much advantage? They cannot be said to add to the structural strength, but perhaps when the mud freezes and they become very firmly locked in they offer an insurmountable obstruction to any animal that may attempt the difficult task of digging into the lodge. As a rule the bulk of the material employed consists of long sticks of one to three inches in diameter at the larger end and a great deal of short stuff of variable size which forms an irregular network. Fibrous roots add greatly to the strength of the work by binding together all the loose material so solidly that it is a task of the utmost difficulty for a man to pull it apart unless he is armed with a pick-axe or crowbar. A well-built lodge will even withstand the destructive power of running water. In Newfoundland I noticed one house while it was being built and remarked on the thoroughness of the work. During the following spring the heavy rains and melting ice and snow caused a flood, which raised the river about eight or ten feet above the normal level. Needless to say the house, whose base was only a foot or so above the ordinary water-line, was entirely submerged, but though the current was swift and continued for several weeks with this unusual depth of water, the structure of the house remained almost intact, only the loose earth and sod being washed away. Of course the beaver had to abandon their home, and they sought temporary shelter in a high bank beneath the roots of some fir trees. Accidents such as these are of frequent occurrence when the lodges are built on the banks of rivers, as the beaver have no control over the depth of water, and such lessons have taught the intelligent animals the advantage of making dams which maintain a more or less constant water level. They learn by sad experience and when they disregard such lessons they have usually to pay heavily for their mistakes. The river-bank lodges or highly-developed burrows are frequently subject to disaster through rising water, and may be regarded as the work of beavers whose intelligence is some what below normal. It is well worth observing that these bank lodges or burrows are most often the homes of solitary beaver, those who, perhaps, through their lower development have been turned out of the colonies to shift for themselves. It is possible, of course, that they are only afflicted with the curse of laziness, but this is doubtful, as it is a somewhat rare fault in wild animals. We have yet much to learn about beaver, and many of our ideas as to the why and wherefore of what they do are based on surmise, which is the result of our very insignificant knowledge. The situations chosen for the lodges vary entirely with conditions. In some parts of the country the beaver appear to realise the advantage of placing their lodges on the north or north-western side of lakes and streams. By doing this they gain the heat of the sun, which melts the ice away from both bank and lodge and so liberates the animals at the earliest possible date. This I have observed particularly in Newfoundland, where most of the lodges seen during a period of several years were thus situated with apparently no other object in view. Concealment seems very frequently to be carefully considered, in which cases the lodge is hidden in dense alder thickets or among closely-growing tamarack or spruce. So effectual is the concealment afforded by the scrubby growth that, were it not for the dams or the peeled wood which is found floating near the shore, their existence would be unknown even by those whose eyes are trained to see clearly. As an instance of this, I remember going to see a place where for months some beaver had with untiring persistence built a dam in a railway culvert. Once or twice each week during their activities the section men visited the culvert and pulled out all the accumulation of brush and sod which obstructed the waterway. Where the lodge was they could not tell, though they had gone all through the alder swamps in search of it, and they declared that there was no lodge. This seemed unlikely, as the nature of the land precluded any possibility of a bank burrow. After a careful examination of the vicinity I found it actually on the railway embankment not ten feet from where trains were passing every day, but it was so cunningly hidden in a small, thick clump of alders that it was almost indistinguishable, even though it was fully eight feet in diameter. In complete contrast to this one finds the lodges on the bleakest barrens, away from any trees or shrubs, conspicuous black (being made of pond muck) mounds which are visible for a mile or more. When entirely protected by water there is seldom much attempt at concealment, and one of the most common types is the lodge built on an island, artificial or natural, in the middle of a lake or small pond. So also is the lodge often seen on a bare point of land extending into the lake. As this does not have the protection of the water it makes us wonder whether or not the animals place any importance on concealment, or whether it is simply a matter of individual ideas. We do not realise sufficiently how strong individuality is in animals when we attempt to generalise or lay down hard and fast rules to govern their actions. It would be far easier for us to understand and account for what they do if we would only start out with the idea that both animals and birds, though governed by certain very definite laws, have the use of a limited free intelligence, which enables them to take advantage of conditions and accomplish things which are apparently not in keeping with what might be done by others of the same species. It is this individuality which helps animals to adjust themselves to new conditions, whereas if they adhered too strictly to the rules which have governed them in the past they would, through the lack of power of free thought, fall easy victims to new and adverse conditions.

Having now seen what the beaver’s lodge is like, we may take into consideration the dam which is the direct adjunct to the house or rather to the more advanced type of house. Just when or how dams first began it is impossible for us to say, but the chances are they are the result of a very gradual development through perhaps thousands of years. So far as I can learn the beaver of the old world did little or no important dam building, but his close cousin on the American continent has without doubt been building them for a very long time and with some very extraordinary results. (These will be dealt with in another chapter.) As already stated the primary objects of the dams appear to be four-fold, the most important being apparently that water may be maintained at a constant level in order that the house shall be safe from attack. Whether or not we are correct in our surmise, we know that the dams are built and that they represent by far the most conspicuous work accomplished by any living animal. As feats of engineering skill they must command our highest respect, as examples of industry they are difficult to excel, and as an exhibition of intelligence they are only equalled or perhaps surpassed by the extraordinary, though less conspicuous, canals which are planned and constructed by the same animals.

There have been many fabulous accounts of beaver dams, in the most ridiculous of which the animal has been accredited with “driving stakes as thick as a man’s leg into the ground three or four feet deep” and with making regular hurdles on the dams. In fact there has been no limit to the fanciful stories on the subject. Even the generally accurate accounts of Father Joseph Jouvency, S.J. (1610-13), from whom I have already quoted, bear evidence of slight exaggeration. He says, in describing the dams: “If they find any river suitable for their purposes, except in having sufficient depth, they build a dam to keep back the water until it rises to the required height. And first by gnawing them, they fell trees of large size; then lay them across from one shore to the other. They construct a double barrier and rampart7 of logs obliquely placed, having between them a space of about six feet, which they so ingeniously fill in with stones, clay, and branches that one would expect nothing better from the most skilful architect. The length of the structure is greater or less, according to the size of the stream which they wish to restrain. Dams of this kind a fifth of a mile long are sometimes found.” This is a strange mixture of truth and error which is difficult to account for. The double barrier and rampart filled in with stones and clay and branches is very far from the actual construction. As a matter of fact, the building of an ordinary dam consists originally of a number of sticks and brush being laid (no stakes are driven) in the water with the butts up-stream. When slightly weighted with sod, stones, and water-soaked billets of wood they become anchored, each projecting twig acting as a brace against the bottom. Little by little more material of the same description is added until from shore to shore there is an unbroken line which at first only slightly retards the flow of the stream. Then sod and muck, with roots and grass, are laid against the upper side or face. By the force of water all this material is worked in among the network of sticks, the beavers assisting the water by pushing clots of fibrous muck, usually gathered from the bottom of the pond, into the openings until gradually the face of the dams assumes a smooth appearance levelled to an angle of about forty-five degrees. If the work is properly done, and beavers vary in the quality of their work just as men do, the structure is finally practically watertight. Yet the word finally is scarcely the right word to apply to a dam, for so long as the beaver have any need of it they continue adding to both its height and length. What begins by being a perfectly complete dam, perhaps twenty feet long and a foot or two in height, ends with a length of many hundreds of feet and a height of six or seven feet or even more. Besides the above-mentioned materials stones are frequently employed in the construction of dams. In fact it is rare to find any that have not at least a few stones worked in with the sod, particularly towards the ends. When so few are used it is hard to say what purpose they serve. But there are instances of dams being built in which stones form the larger part of the material. These are not common and I have never seen but one example. Unfortunately the photograph shows only those stones which are above water, where there is a fair proportion of other material, but below the surface there was little else than stones of small size, none weighing more than three or four pounds. Very much larger ones are frequently used; in fact, I have been told by trappers of some that weighed about thirty or forty pounds and even more, and Mills speaks of stones weighing upwards of one hundred and twenty pounds being moved into position on the dams by the united efforts of many beavers. Never having seen any heavier than nine pounds, I cannot guarantee the correctness of the trappers’ statement, but Mills is a careful and very accurate observer and thoroughly reliable. Generally speaking, it is not wise to be too incredulous, and any information, to have value, should be the result of very careful, personal observation. Otherwise the source of the information should be given. Many of the trappers are blessed with a keen and rather subtle sense of humour, and few things give them greater pleasure than filling up the stranger with yarns, and they derive a real joy if they ever happen to see these same yarns in print, especially if the “facts” are given as though they were entirely original with the writer. On more than one occasion has a trapper told me of how he had tricked the tenderfoot into believing most fabulous stories of the ways of wild animals. Some of course tell of strange happenings, not with the idea of having fun, but they enlarge on already much enlarged stories that have been retailed to them. Few stories shrink in the telling, while most grow with alarming vigour, and if we would believe all that is told of beavers our minds would be filled with most marvellous “facts” more wonderful, even though less reasonable, than what is accomplished by these interesting animals.

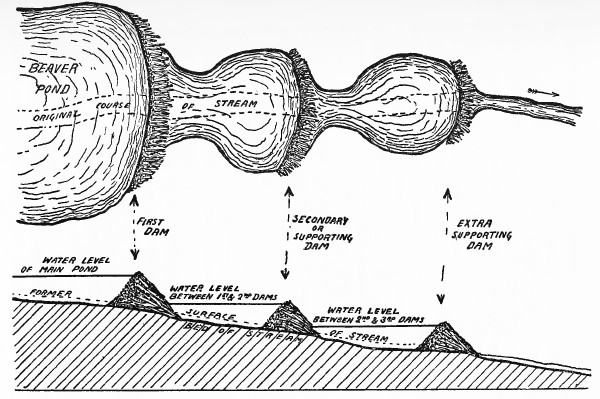

In practically everything that is done by them we can, if we use a little care, discover the object, and though at first glance we might sometimes be led to imagine that improvement could be made in the method, if we go far enough into the question and thoroughly appreciate the animal’s point of view, his needs and the natural restrictions of his ability, we are nearly always forced to acknowledge the success of his methods. Certainly in the building of the dams, improvement both in the choice of site and the actual execution of the work is most difficult to suggest. Indeed it is very doubtful whether the average man could, without tools, or even with the help of an axe, overcome the obstacles which are encountered by the beaver. Most writers in dealing with the subject are inclined to pay too much importance to the curve of a dam. Some assume that all dams are built with the curve against the current, others that such is the case only when the flow of water is swift, while some claim that the curve is most often down stream. I have seen a great many dams built in many different situations and under very different conditions, and the conclusion which has been forced on me is that there is no rule to govern the curve. It just happens. I have seen quite large dams, two or three hundred feet long, which were almost straight, others had a decided curve up stream. Others again, under apparently similar conditions, were curved with the current, while on more than one occasion the dam has been like a drawn-out letter S, that is to say with half of it curving up and the other half down stream. On the whole, I think the subsidiary or supporting dams are more likely to be straight or have the curve away from the main structure. These subsidiaries are of very great interest, as they offer a clear example of the beaver’s forethought, that is, if we are right in our conclusions, for we believe that they are placed below the most important dam in order to support it, by backing the water against its base, and also for the protection it gives when the pond is frozen, for then the mass of ice which forms in the usually quiet water acts as a powerful support to the principal structure, which has to resist a terrific pressure of ice, snow and water, especially at the time when winter is breaking up. But there are probably other reasons for the existence of these extra structures. It will be noticed that frequently there are a number of them — sometimes as many as eight or more at distances apart which may vary from a few feet up to several hundred. Some are of quite imposing size, while others may be only insignificant affairs a foot or two long and very roughly built. Between each dam, there is usually water of sufficient depth to allow the beaver to hide and so escape his enemies. Then again there is another important reason for these lesser dams. No matter how well the main structure is built, how carefully it is designed, an unusually heavy volume of water may cause it to break. The result of such a calamity would be that the pond would be lowered and the entrances to the lodges exposed, perhaps even the beaver would be left without any place of retreat. The subsidiary dams would greatly lessen the dangers as they would retain the water to a greater or lesser depth according to the conditions. There would be still another advantage in holding back the water, as it would make the repair work or rebuilding of the main dam a matter of much less difficulty owing to the decreased force of the current. Taking all things into consideration, we can see how important are these secondary or supporting dams and how greatly they reflect credit on the animal’s power of reasoning and application of this power. For by doing what apparently is a vast amount of extra and, at first glance, almost unnecessary work, the beaver is taking steps to prevent a possible catastrophe. Surely he must reason this out, for otherwise how would he know that great rains do come, and even the greatest dams do burst. Does he learn it by seeing some of the very small structures give way under pressure slightly more than normal? But who shall answer these questions? In building the smaller dams, the method of construction differs in no way from that already described; only in point of size are they different. As a rule they are not large, seldom more than about thirty feet in length. Exceptions there are to this, but speaking generally, they are below this length, while the height is in accordance with the demands of the stream. The more rapid the current the higher the dam. In very flat country, where the waterways are sluggish, and these are the most sought after by the beaver, they are usually not more than a foot or two in height. Few streams are too large, and none too small for dams. I have seen a stream less than two feet wide on which there were no less than seven within a distance of scarcely one hundred yards. Their chief object, apparently, was to keep the water from draining out of a flat alder swamp, from which the beavers were busily engaged in getting their winter supply of food. To have hauled branches through the tangled undergrowth would have been a difficult task, but by keeping the water only a few inches above its normal level they could make channels among the hummocks through which they could with comparative ease swim with the branches and sticks.

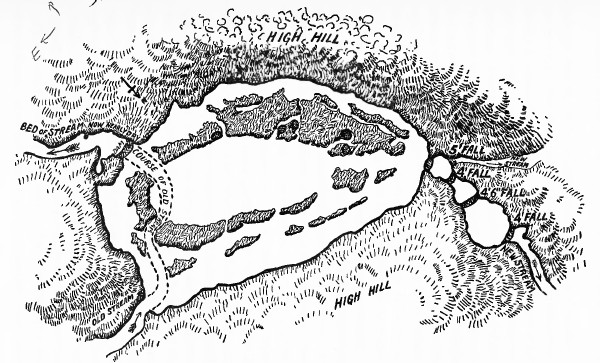

In selecting the site for the dam, the beaver shows a remarkable power of discrimination, and one wonders how it is that so short an animal can possibly make any survey of the country and get any appreciation of the conditions. They have two principal objects in view when selecting the site for a new house; an abundance of water, and trees whose bark is suitable for food. These are their needs, but the question of obtaining and controlling them requires serious consideration and much careful planning. Good sites for house and dam are not found everywhere, neither is an adjacent food supply, while for the combination they must have to search over many weary miles. It would be most interesting to know their methods. Do they deliberately go out on “house hunting” expeditions, examining everything as they go along, and following each stream either to find its source, or discover springs which will ensure sufficient water in the stream during the dry season? Whatever is their method, the results are in nearly all cases eminently successful. The work of hunting for a suitable place to establish a house is done during the summer months, for then the beavers do not usually occupy their lodge. They wander about the country, nearly always following the waterways. If, for any reason, it is their intention to found a new colony, they remain in what seems a desirable situation, living in bank burrows instead of lodges, while the possibilities are thoroughly investigated and plans apparently made for building the dam. A stream flowing through country well wooded with poplars and hardwoods is usually chosen, and the work begins at any time during the summer, though more often towards the approach of autumn. Sometimes, indeed, no attempt is made until as late as the beginning of cool weather, but there seems to be every reason for believing that they prefer the time when the streams are at their lowest, which is August. Then they see what is the minimum supply of water, and the dam may be built with the least possible trouble. When they finally settle on the exact site, the first sticks are laid, and these in most cases are freshly cut and not peeled. Alders are perhaps the most frequently used, as they are found growing along the waterways and are therefore easily obtained, while their weight allows of their being sunk without much difficulty, and their irregular form of growth helps them to hold on the bottom against the current of water. How quickly a dam is built depends entirely on the urgency of the situation. If it is late in the year, the building proceeds with incredible speed, little more than a week of steady work on the part of a family will see a thirty or forty-foot dam raised to a height of two feet or more. As soon as it backs up the water, the house is commenced and we find that all the different tasks are being attended to simultaneously — dams, both main and subsidiary, lodges, tree-cutting, and storing of winter food. Within a few weeks the colony becomes established and the face of the land is changed by the work of these small animals. Larger and larger the pond grows, as the dam is extended, while the banks are covered with fresh, white stumps of fallen trees, as though a gang of lumber-men were at work. Each night sees marked changes resulting from the untiring work of these builders and tree-cutters. If the colony is successful and the site chosen proves entirely satisfactory it will continue to grow as the years go on, each year seeing the extending of the dam, and, if necessary, the number of subsidiary dams increased. The trees whose base has been flooded by the rising water gradually die, and the gaunt grey columns bear witness to the effect that beavers’ work has on the land. So long as the supply of suitable food trees is to be found the colony remains, unless killed off or driven off by the trappers, and so it is that such immense dams are found, some over two thousand feet in length with a height of from two to about fourteen feet, the result of countless generations of industrious beavers, not necessarily working continuously, for they often abandon a pond for many years, apparently to give time for the food trees to grow. On their return, or if a new colony takes possession, they have a busy time repairing the dam and getting everything in proper order.

The solidity of the structures is perhaps best proved by the fact that some have been found in Montana which were in a partially petrified state. As a rule, however, the life of a dam is but a few years beyond the period during which it is used; owing to the nature of the material employed, constant supervision and repair are absolutely necessary. The beaver realise this and seldom allow a night to pass, during the autumn, without making a tour of inspection and building up and strengthening any part that shows signs of weakness. The smallest hole is soon enlarged by the pressure of water passing through, so that if it is not speedily closed the destruction of the whole structure is threatened; rats, musquash and otters sometimes burrow through the dams and cause untold damage. How persistent the beaver is in repairing is well illustrated by the following experiment made in the Algonquin Reserve. Knowing that the best way to secure flashlight photographs of the animals at work was by making a break in their dam, I selected one within convenient distance of where I was staying. After arranging the cameras in position, I made an opening in the dam about two feet wide and laid a thread across. This was attached to the electric switch which operated the flashlight and shutters of the cameras. Scarcely three hours elapsed before the animals, who had found that the water was rapidly escaping from their pond, visited the dam and repaired the breach. Before midnight I returned and reset the cameras, after again opening the dam. Before morning this had again been mended. After that I continued each night to repeat the operation, breaking open the dam at least once each night, sometimes twice, and on two occasions three times. During the twenty-two nights, only twice did the beaver fail to more or less completely fill in the openings I had made, though they never once did so while I remained to watch, even though I took every possible precaution not only to conceal myself, but to select a position down wind of the dam, where I remained sometimes during the greater part of the night. When a dam is abandoned, it is soon worn down by animals using it as a roadway, or it is overgrown by alders and willows, whose roots cause a certain amount of leakage, so that the pond is gradually drained, and in a very few years there is little to show that a dam ever existed in the place. Among the many interesting features of the dams, there is one which speaks most highly for the builder’s intelligence. That is the method adopted for taking care of the overflow. In most cases, the water finds its way through the loose brush near the crown. This is well enough under normal conditions, but when the dam is on a good-sized stream so that there is a large volume flowing from the pond, the beaver frequently make a spill way or opening a few feet wide, and deep according to the conditions. These openings are quite clearly defined, and are evidently made with a full understanding of their purpose. For when there is a scarcity of water, the intelligent animals close the opening as much as may be necessary. This shows how thoroughly they realise what they are doing when building their dams, and how they understand the value of controlling the outlet of the water. They are always ready to grapple with new problems, and no ordinary contingency appears to baffle them. I saw an instance in Newfoundland which may be worth repeating: a small colony of beaver were engaged in building a dam across a swift stream about forty feet in width. Before the work was quite finished, so that the dam had not yet settled enough to gain its proper strength, there came a great rain which continued for several days and flooded the country. The beavers, seeing that their new dam was threatened with immediate destruction, came down during the night and made a large opening by cutting away the sticks. This allowed the water to escape and so the dam was saved. No sooner had the water resumed its normal level than the little engineers closed the break they had made and continued the structure to its completion. For fear that I might have been mistaken and that the opening had been made by the force of the water, I examined it carefully and found the tooth-marks on the sticks showing with out doubt where the animals had cut them away: and it is of interest to note that Father Jouvency, as long ago as 1610-18, made note of this same thing being done. He says: “But if the river swell more than is safe, they break open some part of the structure, and let through as much water as seems sufficient.” The more we study the beaver dams the more we must recognise the care exercised in the selection of their sites. Everything seems to be considered and every advantage is taken of the prevailing conditions. In the photograph there is an example of how cleverly the small creatures utilised an immense boulder in the middle of a rapid flowing stream. Rocky bedded waterways offer many and serious difficulties to the beavers, for it is hard to get anchorage, and in this particular case the current was so swift that to build a successful dam required unusual skill. Evidently the beaver made a thorough investigation of the little river and finally selected what was about the only reasonably good place for their operations. The large boulder acted as a support or anchor for their work (this can be plainly seen in the photograph), so that when the structure, which was over four feet high, was finished, it resisted the flow of water and formed a fair-sized pond and an island on which the beaver built their lodge. Some writers have claimed that the animals begin their dams by felling a large tree across the stream. This may be true, but I have never seen an instance of it. What does often happen is that a fallen tree lying across a stream suggests a good position for the dam, or a floating log carried down during the spring thaws becomes lodged against the stream banks so that the beaver take advantage of it and build against it. Except under conditions of this kind it is unusual to find the timber, whether stick, brush or log, placed so that it lies in any way but with the course of the stream. This is reasonable enough when we consider how little cross-pieces would add to the strength of the dam, and they would be easily dislodged by the pressure of the flowing water. Whereas when placed with butts upwards and headed against the current, the points are forced against the bed of the river and as weight is added to them they offer a barrier of great strength, capable of resisting any ordinary pressure of water. When the supply of water is too limited, the beaver take the utmost care to see that none is wasted, and the dam is coated with unusual care to render it practically watertight even towards the ends, and every tiny trickle is stopped, sometimes by little dams only a few inches long, just a handful or two of sod placed in exactly the right position, perhaps some distance from the actual structure. If during the autumn these are trodden down or broken they will nearly always be repaired within a few hours, so careful is the supervision of the beaver.

For some reason which can only be guessed at, the beaver nearly always leave a roadway across the dam leading from the pond to the outlet. This is also much used by other animals of aquatic habits such as mink, musquash and otter, and though occasionally we also find a well-beaten path running along the dam from bank to bank this is not a beaver path. More often it is the work of foxes, deer, lynx and other prowlers of the woods, as well as man, who finds these “bridges” most convenient. Many a time have I found myself at a loss for a way of crossing a stream until the fortunate discovery of a beaver dam has enabled me to avoid a wetting. Having now seen something of the dams, so that without going into a lot of tiresome and unnecessary detail such as exact measurements of numerous structures (which must vary continually), the reader has at least a general idea of what they are like without, I hope, being too much bored. We have seen that the dams range in length from a few inches to two thousand feet or more, and in height up to fourteen feet, containing from a pound or two of building material up to several hundred tons, all carried laboriously by the industrious builders in their tiny hands or with their powerful teeth. Also that the idea of this stupendous work is to enable the animals to keep water at a constant level for the protection of their lodge and to furnish them with a convenient means of transporting their supply of wood. This brings us naturally to their wood-cutting operations, about which many wonderful tales have been told. Before going into the methods, it might be well to give the reason for woodcutting even at the risk of slight repetition. Beavers’ natural food consists of a purely vegetable diet, the chief item being the bark of trees, not the outside shell, but the cambium layer which contains the very life of the tree. To a limited extent they also use the wood itself, but the nutriment obtained from it is so insignificant that it is only occasionally used. Nearly all of the deciduous or broad-leaved trees supply food for the beaver, but the most sought-after are perhaps the different birches, maples, poplars, willows and ashes — to a less extent, alder, viburnum, dog-wood, wild cherry and others according to the locality. The bark of the conifers is not much used, some authorities say that it is never eaten, yet the trees are frequently cut down by the beaver. I have seen several instances, but none of them had any of the branches cut off. From Indians and trappers, I have been told that immediately before the young are born or about that time, the prospective mother eats a small amount of spruce, pine or other conifer bark, which I they believe to have some medicinal property. During the spring and summer, many kinds of roots and berries are eaten, and at all seasons the roots of water-lily and spatterdock are used. In certain districts these form the main supply even during the winter, when the beaver come out of the lodges, and beneath the ice gather the roots as they are needed and take them into their houses to eat. From this habit has come the curious superstition that a beaver if shot in the evening sinks, while if shot in the morning he floats, because he is filled with the light, pithy substance of the lily root which has been eaten during the night. Needless to say, this is scarcely likely to be true, though, as I have never shot a beaver, I cannot speak from actual experience. Now it will be noted that bark is the chief food, and that in order to obtain a supply sufficient to carry the animals over the long, dreary, snow-bound winter months a quantity must be stored. Needless to say, this necessitates the felling of trees and saplings before the cold weather comes. A certain amount of brush is used from which the tender bark is eaten, and most of this brush is obtained from the ends of branches, although some shrubs are also cut. Apparently not so much bark is eaten during the spring and summer as later, if we may judge from the peeled sticks which are found in such abundance in September, October and November. During the earlier part of this season, no wood is stored, though many trees are either cut or partly cut, while still more are simply marked or blazed, as already stated in the beginning of this volume. This blazing at first glance reminds one of the work of the lumber-man and we are inclined to put a wrong construction on beavers’ ideas. We might think that the trees are simply being marked for cutting later on, or that the head of the family or colony selects what trees he considers should be felled and marks them with the three or four cuts. But though such theories are most alluring, and one is surprised that they have not led to additional stories of beaver-wonders, common sense steps in and offers a logical reason which should be considered, even though it is merely practical and not at all particularly wonderful. This explanation is that in order to keep the bark perfectly sweet while under water for a considerable time, the tree must be in a certain condition, otherwise the bark might ferment or in some other way become unfit for food. The only way in which the beaver can assure himself of the tree’s condition is by biting into the inner bark, therefore this would account for the numerous blazed trees which may be found in the vicinity of the ponds and lodges. Carrying this idea a little further, we have also a possible explanation for the fact that such a large number of trees are girdled and left often for weeks before being finally dropped. This girdling allows the tree to dry more quickly than if left with the bark on. The acceptance of this theory means, of course, that we are endowing the animals with extraordinary intelligence; but how can we avoid doing so when we see what they accomplish? When I first described this systematic marking of trees, I was ridiculed, partly because it had not previously been brought to anyone’s notice (so far as I know), but the fact that it is commonly done by beavers can be proved by a visit to any place where the animals are preparing to store their winter food, and as a reason for its being done these theories are offered simply as theories.

It has often been said that cutting down trees is the most wonderful work accomplished by beaver, but how such a conclusion can be reached is difficult to understand. Nearly all of their efforts demand far greater intelligence, though from a physical point of view the cutting of immense trees by so small an animal is extraordinary, if not unique in the world of quadrupeds. Just as in all their other engineering and architectural feats, the beaver are most systematic in their wood-cutting operations; as a rule the trees bordering the pond or river are the first to be cut, then as this supply is depleted they go further afield; but as the carrying and pushing of logs on land is hard work they clear a path or road to the water. When they discover a place where there is a poplar grove or clump of suitable trees of any variety, they will, before beginning other work, make a smooth road way, often as much as five feet or more in width leading from the trees to the nearest water. From this road every obstruction will usually be cleared so that the logs may be brought down with the least possible effort. The actual cutting down of the tree is done by means of the chisel-like teeth which cut through the wood across the grain with the keenness of steel. The number of beaver that work together is variable, often a solitary one unaided will cut down a tree eight or ten inches in diameter during a single night, sometimes several will work together; though it is most unusual for more than two to be actually cutting at the same time, others may be near by, and even take turns, but they avoid getting in each other’s way. It has often been said that while a tree is being cut, one beaver stays some distance away and watches the top. At the first intimation of its falling, he signals by either slapping the ground or the water with his tail and the others immediately run away. Unfortunately, I have never been an eye-witness of such a performance, and even though I have heard many trees being felled — some within forty yards of my camp — I have never heard the signal, nor have I seen the beaver on watch. Besides which, it scarcely seems reasonable that the animal while cutting should need any notice of the tree falling. With his teeth against the wood, the creaking sound of even the beginning of the fall would be very evident, even if he did not hear the top brushing against the other trees on its down ward path. Animals do not do unnecessary things, and this warning certainly seems unnecessary even though it may be true. That the beavers remain fairly quiet for a few minutes after a tree has crashed to earth is quite possible, though it is not by any means always done, while the explanation usually offered does not sound altogether right. Why should the sound of a falling tree attract enemies? Such sounds are only too common in the forests, and the noise made by the biting of the wood is so loud that even a man with his dulled sense of hearing can distinguish it many hundred yards away on a still night. If the beaver does stay motionless after the crash there is probably some other reason — possibly it is for the purpose of resting. From the very different heights of the stumps it is obvious that the beaver follows no hard and fast rule in cutting. Frequently stumps four or five feet in height are found. These of course are done when the ground is covered with well-packed or ice-coated snow, except in cases where the animal stands on a convenient log or mound of earth, and so reaches high enough to avoid the bulging part of the trunk near the ground. That the beaver ever make piles of earth for the purpose of having an elevated platform is hard to believe, notwithstanding what has been written on that subject. The origin of such stories is probably the mounds of moss-covered earth or decayed tree stumps which are so often found close against growing trees, marking perhaps the tombstone of the parent of the existing tree. These mounds are quickly worn down by the beaver standing on them so that they have the appearance of being made of freshly collected mud or earth. In cutting, the beaver sometimes stands erect and cuts as high as he can reach, then again, judging from the very low stumps, some of them stand on all fours, but the usual method is to stand on the hind feet with the broad tail stretched out behind to act as a balance. Either one or both front feet or hands are placed on the trunk. In most cases, the cutting is done all round the tree as shown in some of the photographs, while occasionally, owing to the position of the tree, the cutting is done entirely from one side. This, of course, involves far greater labour on account of the larger opening being necessary. The size of the chips which are cut by the beaver is truly extraordinary. If the wood is soft, such as poplar or cedar, they will take out pieces fully five inches long by an inch and a half wide and three quarters of an inch in thickness, while with hard woods such as maple or birch, the chips will be usually three to four inches long and one and a half wide. Much larger chips are sometimes found, but they are exceptional, and must not be taken as the rule. Nine inch chips are mentioned by some writers, but they were perhaps cut for bedding purposes, to be taken in the lodge and shredded, and can not, therefore, be regarded as chips cut during the felling of trees. From the size of the tooth scars, the size of the beaver may be judged. Many other tales do they tell. Often the mark of a chipped tooth is found, which shows that the animal had probably been caught in a trap and broken the tooth by trying to bite the cruel steel, while dull and rough edges are evidence of the great age of the beaver, just as the narrow cuttings are the work of the youngsters. The upsetting of pet beliefs is always a thankless task; but this is not a book of fairy tales. The truth, so far as possible, must be told even at the risk of being called to account for being too practical and not indulging sufficiently in romance. The popular notion that the beaver knows exactly in which direction a tree will fall is not borne out by fact, and I feel sure, after having made a careful study of the subject, that the direction is purely a matter of chance. It is quite true that most trees growing near the water fall towards it, but this is not due in any way to the wishes or skill of the animal, but to the obvious fact that trees grow towards light. The water, being an open space, attracts them; therefore when cut it is only natural that they should fall the way they are inclined. Another common fallacy is that the beaver never makes mistakes in tree cutting. Quite a large proportion of the trees they cut lodge in the branches of their neighbours. When this happens they are usually abandoned without further effort, but sometimes we see cases which prove the persistence of the little woodsmen. Not only will they cut through the trunk a second time, but even a third or fourth time, in the hopes of attaining their object. The photograph shows a good example of this. The tree, a birch, ten inches in diameter at the stump, was cut through twice without bringing it down. A third attempt was made, but not quite completed at the time that the photograph was taken. It is not to be wondered at that the little creatures should make such mistakes, considering the fact that their eyesight is only fairly good, and that as they work almost entirely during the night they can scarcely be expected to see clearly the tree-tops which are perhaps forty or fifty feet above them. How often does man make exactly the same mistake? Yet he works in broad daylight and has far better eyesight. When a tree becomes lodged, the beavers’ method of solving the difficulty is usually quite different from our own. We seldom cut through the same tree a second time, but choose rather to cut away the obstructing tree. The beaver, on the contrary, nearly always confines his efforts to bringing down the tree he wants by repeated cutting. Only very rarely do they adopt the man’s method. In cases where a tree falls so that it comes nearly to the ground either through being entangled in another tree or held up by its own branches resting on the ground, the beaver make their way along the inclined trunk and cut off the supporting branches or, if not too thick, the top of the tree, so that it shall fall to earth and be more easily manipulated. The great weight of the beavers’ body and the formation of their feet prevent their climbing a vertical trunk, but when it inclines to an angle of even forty degrees they manage to walk along the rough bark without difficulty. Often have I found branches cut off which were eight or ten feet from the ground, but seldom at any greater height.

The size of trees which beaver will cut is almost incredible. The largest I have seen was twenty-two inches in diameter where the cut was made, that is to say, about sixty-six inches in circumference, a tree large enough to give an amateur axe man a lot of trouble. There are accounts of still larger trees being brought down by the industrious little woodsmen. Lewis and Clarke mention having found trunks which measured nearly three feet in diameter, and Mills says: “The largest beaver-cut stump that I have ever measured was on the Jefferson River, in Montana, near the mouth of Pipestone Creek. This was three feet six inches in diameter.” He omits to mention the species of tree, but it was probably a cotton-wood, as it is impossible to imagine the animals attempting to cut anything harder when the immense size is considered. A tree having a circumference of approximately 126 inches must offer almost insurmountable difficulties, but, when successfully felled, the animals would at least experience the satisfaction of having a very liberal supply of food, enough perhaps to last a family all winter. Trees of these sizes are of course exceptional; the usual size ranges from four to ten or twelve inches in diameter. These are more convenient to handle, and in the end offer a more economical undertaking, as they can be cut up and every part, including trunk and branches, can be used, whereas if the trunk is too large, they never attempt to cut it into short lengths suitable for transporting to the food pile. Seldom indeed do they divide a trunk having a maximum diameter of more than eight or nine inches. Even this size necessitates a great deal of labour, as, in order that they may be easily handled, the logs must be very short, not longer in fact than a foot and a half or two feet. The beaver knows the weight of wood to a nicety, and he divides the logs and branches into lengths which can be handled. This, one may say, is instinctive. Perhaps so. But it looks uncommonly like reasoning. It certainly requires something very closely akin to intelligence to work out the weight of a long prostrate log, so that as the diameter decreases the distance between cuts increases, with the result that each piece is of more or less the same weight. There is nothing haphazard about it, and though the beaver have no callipers or measures, they seem to know by looking at the log what proportion the length should have to the diameter, and seldom do may make any very great mistake in their calculations. Abandoned logs are found, but whether left on account of their excessive weight or from some other cause we cannot say for certain. It is more than likely that the wretched creatures become so absorbed in their labours that they fail to detect the stealthy approach of some enemy, and so fall easy victims, the forsaken log remaining to mark the place of the pitiful tragedy. The methods adopted by the beaver for taking the logs down to the water are various. When the branch is small, or long and thin, it is usually carried in the teeth, the larger end forward if it has many twigs, otherwise the smaller and lighter end is held in the teeth so that the remainder hangs over the animal’s shoulder. Sometimes the beaver proceeds in this way on his hind feet only, with his front feet or hands holding the branch. Heavier logs are pulled or pushed either with the head, chest or even the hips. Whether more than one does this work I have never been able to assure myself, but I think it is usual for a single beaver to take complete charge of his own log, get it down to the water as best he can, and then swim with it to the wood pile, where he sinks it or places it on the top, according to his own ideas. How the sinking of the wood is done has given rise to many fanciful tales. Some trappers firmly believe that they suck the air out of the wood so that it will easily sink. Anything more absurd would be hard to imagine. As a matter of fact, all the hard woods have a specific gravity nearly equal to that of water, so it requires very little effort to take them down. Many a time have I watched the beaver swimming across their pond with a branch, and on arriving at the food pile dive under water, taking their branch with them. How they manage to keep the wood from floating is somewhat difficult to understand, but they succeed in doing so most effectively. I have never seen the short, thick logs carried down. They appear to be forced under water by the weight of other material which is piled on top of them. The size of the wood piles varies according to the number of beaver who are expected