No rains had descended, the

fountains were dry,

The streamlets no water

afford;

No clouds thick and heavy

bespoke a supply,

When a voice to Elijah

descends from on high,

And spoke the commands of

the Lord.

Arise, O Elijah! to Zion

repair,

Awhile in Zarephath remain;

A poor widow woman will

welcome thee there,

To thee of her little a

portion will spare,

And with food and with water

sustain.

The Prophet arose at the

heav'nly desire,

His steps to Zarephath he

bound,

When lo! the poor widow in

humble attire,

And busied with gathering

sticks for her fire,

At the gates of the city he

found.

He said, "I have

travell'd a wearisome way,

"From Cherith to-day I

have hied;

"I have passed by no

fountain my thirst to allay,

"Then fetch me a

draught of cold water I pray,

"Lest I perish with

thirst at thy side."

She turned, when again to

the woman he spoke,

"A stranger am I in the

land,

"And since in

compassion my thirst thou wilt slake,

"Remember I also am

hunger'd, and take

"A morsel of bread in

thy hand."

She answered, "as

liveth thy Maker and Lord,

"No bread for thy

hunger have I;

"Of oil but a little my

cruise can afford,

"But an handful of meal

in my barrel is stor'd,

"And from none can I

ask a supply.

"For fuel to dress this

small portion to day,

"To the gates of the

city I hie,

"And now with these

sticks I return on my way,

"That my son and myself

may our hunger allay,

"Then calmly resign us

to die."

Then answer'd Elijah,

"as thou hast begun,

"Go on till thy home

shall appear;

"Make cakes of thy

meal, and first bake for me one,

"Then after another for

thee and thy son,

"And your hunger allay

without fear.

"For thus saith thy

Maker, the meal shall not waste,

"And the oil in the

cruise shall not fail,

"But thou and thy

household his bounty shall taste,

"Till the day when his

wrath and his anger is past,

"And showers of plenty

prevail."

No need had Elijah the words

to repeat,

To the house of the widow he went;

Many days he sojourned in

the quiet retreat,

And she, and her son, and

the prophet did eat,

And the oil and the meal

were not spent.

Yet more would you hear how

this widow was bless'd,

How her son from the dead

was restor'd,

Go turn to the book where

the tale is express'd,

Of Elijah, belov'd of the

Lord.

What little smiling boys are

those,

Which hand in hand we see,

They are two brothers, I suppose;

How pleas'd they seem to be!

No, but those little happy

boys,

Are cousins to each other,

Though none could love more

than they,

A sister or a brother.

And Robert and his Cousin

play,

So prettily together;

Their friends delight to

take them out,

To walk in pleasant weather.

And when the steam-boat's

coming in,

'Tis grand-papa's delight,

To take the children to the

shore,

To see the pretty sight.

Is this new life so sweet to

thee, my little baby boy,

That thus thy minutes seem

to be a constant course of joy?

I gaze upon thy laughing

face, I hear thy joyous tone,

Till the glad feeling of thy

heart, oft passes to my own.

No titled infant for whose

brow, a coronet shines fair,

Is blest with better health

than thou, or nursed with tenderer care;

And be it prince or

peasant's child, the station high or low,

These blessings are the only

ones its earliest days can know.

I would not damp thy present

joy with tales of future care,

Nor paint the ills of life,

dear boy, which thou must feel and bear:

The early dew, is fair to

view, although it vanish soon,

And lovely is the morning

flower, that withers when 'tis noon.

Thy heavenly Father, by

whose will a living soul is thine,

By his good spirit visits

still, this heritage divine,

And children who in

innocence the path of life have trod,

Hear often in their tender

minds, the in-dwelling of God.

As reason dawns, as mind

expands, in childhood's opening day,

Thou oft will hear his high

commands, to shun the evil way:

And every evil thought

resign'd to this divine control

Will bring a sweetness to

thy mind, a blessing to thy soul.

Dear as thy welfare is to

me, I cannot frame a thought,

I cannot breathe a wish for

thee, with happiness more fraught,

Than that this heavenly

Friend may prove the ruler of thy way,

And thy young heart incline

to love, to hearken, and obey.

How dearly I love, how.

indulgent you are!

Little William one morning

said to his mamma;

If I had but money, whatever

you need,

Were it hundreds or

thousands, I'd give you with speed.

I would get you a house all

surrounded with green

And a garden, the prettiest

that ever was seen;

I would buy you a beautiful

carriage besides,

And two prancing horses to

take you to ride.

His mother said kindly, your

love must be shown

By obedience at present, I'd

much rather own

A dear little fellow who

minds my commands,

Than carriage, or horses, or

houses, or lands.

William wondered, but

merrily went to his play,

And nothing occurr'd to the

close of the day,

Shut the door little boy,

said his mother at night,

Yet off went the youngster,

unheeding her quite.

Come pick up my needle and

thread case my son;

Directly, mamma, when this

wagon is done,

When that was completed he

moved not a jot,

His mother's desires were

entirely forgot.

When absent a moment, she

left a command,

That William by all means

should keep from the stand,

She feared with the candles

her work might he burned,

Or by his quick motions the

whole overturned.

His wagon was loaded,

himself was the horse,

For a while he remember'd

the stand in his course

But forgetting at length in

his rapid career,

His mother's injunction,

approached it too near.

He stumbled and fell, but

alas! in his fall,

He overturned work-table,

candles and all.

When back came his mother,

her muslin was spoil'd,

The candles were broken, the

carpet was soiled.

She looked much astonish'd,

yet nothing she said,

But took weeping William

directly to bed.

By the side of his pillow

some moments she staid,

And finding him penitent,

did not upbraid.

But patiently showed him how

contrary quite,

His professions at morning

and practice at night.

And after, when feeling his

parents were dear,

He strove by obedience to

make it appear:

And always the maxim most

carefully heeds,

Professions are nothing till

proved by our deeds.

SUMMER

And we forget the winter's

storm,

How pleasant 'tis to walk

without,

While flowers are blooming

all about,

The wind is mild, the air is

sweet,

The grass is green beneath

our feet.

WINTER

We do not love to wander

out;

But choose within the house

to stay,

Where we can work, or read,

or play,

While sitting by the

fire-side warm,

We listen to the howling

storm.

Then children shelter'd from

the street,

With clothing warm, and food

to eat,

Should never cry, be cross,

or fret,

And tease for what they

cannot get.

One morning over hill and

plain,

The sunbeams brightly fell,

And loudly from the steepled

fane,

Rung out the Sabbath bell.

And they who loved the day

of rest,

Went forth with one accord;

Each in the way he deem'd the best,

To wait upon the Lord.

But not with these in lane

or street,

Was Henry seen that day;

He had not learn'd to turn

his feet

To wisdom's pleasant way.

And he with boys of evil

make,

Had plann'd the woods to

rove,

And every tree for nuts to

shake,

Throughout the walnut grove.

With basket o'er his

shoulders thrown,

With garments soiled and

torn,

Young Henry saunter'd from

the town,

This pleasant Sabbath morn.

His widow'd mother, ill and

poor,

Had taught him better

things;

And thus to see him leave the door,

Her heart with sorrow

wrings.

She strove the holy book to

heed,

Which spread before her lay:

But often while she tried to

read,

Her thoughts were far away.

The sun his parting radiance

shed,

Each hour increased her care,

When stranger's steps with

heavy tread,

Came up her narrow stair.

And in their arms her son

they bore,

Insensible and pale,

While many a stain of

crimson gore,

Revealed the hapless tale.

The day he'd spent amid the

wood,

In merriment and glee,

And near its close

triumphant stood,

Upon a lofty tree.

The bough, the very topmost

bough,

Beneath his weight gave way,

And senseless on the rocks below,

The unhappy Henry lay.

With mangled flesh and

lab'ring breath,

And sadly fractured limb,

For many a week he lay, till

death

A mercy seemed to him.

Yet ere its bonds the spirit

burst,

Deep penitence was given,

And thus for Jesus' sake, we

trust,

Acceptance found in heaven.

A damsel, (it must be

confessed

'Twas many years ago,)

Had used be very plainly

dressed,

Nor ribbon, lace, or bow,

Ere'd been thought needful

to adorn

Young Hannah's cap of snowy

lawn.

Of those the world bath

Quakers named

The damsel's parents were,

And Hannah never was ashamed

Of her profession fair;

Yet sometimes in her bosom

rose,

A passing wish for finer

clothes.

A ribbon worn by neighboring

miss,

Had caught her youthful eye,

And much she longed for one

like this,

About her cap to tie;

And felt at length resolved

to be,

At the next visit, fine as

she.

'Twas bought, an invitation

too,

Received without delay,

And Hannah to her purpose

true,

Put on her best array;

And round her cap, with

ready hand,

Arranged the glossy silken

band.

She took her seat among the

rest,

But soon the conscious maid,

Thought a strange smile, but

ill suppress'd,

On every visage play'd;

And hand to head she oft

applied,

To feel if all were safely

tied.

Unto the distant mirror

then,

Full many a glance was

thrown,

Till came the thought, how

strange and vain

My friends will think me

grown,

And with this thought a

crimson glow

Came mantling o'er her cheek

and brow.

Hannah was famed above the

rest

In hours of social glee,

For pleasant tale, and

harmless jest,

And lively repartee;

But now unwonted decoration,

Took all her thoughts from

conversation.

And one remark'd her absent

look,

And eye that wandered still,

Another kinder interest

took,

And asked if she were ill,

Till vexed by all she sees

and hears,

The maid could scarce

refrain from tears.

At home, with readier hand

she drew

The ribbon from her head,

Each wish for novel fashion,

too,

Had from her bosom fled;

Nor from that day was Hannah

deck'd

With aught unfitting for her

sect.

When age had made her visage

pale,

And furrowed deep her brow,

Her children's children heard the tale

Far better told than now,

And each young heart this

moral traced,

Nothing is beautiful,

misplaced.

THE APRON STRINGS

So hardy she had grown,

That though the nights were

long and cold,

The damsel slept alone.

Save when her grandmother

was there,

Who dwelt some miles away,

And when the roads were

rough, to share

Her grand-child's bed would

stay.

Her failing strength, both

shaking head

And trembling hand betrayed,

And grandma often went to

bed

Before the little maid.

For Mary Ann till eight

would sit,

Beside the candle's beam,

And many a winter's stocking

knit,

And sewed full many a seam.

The dame one night had gone

to bed,

And eight o'clock had

pass'd,

When Mary Ann wound up her

thread,

And stuck her needle fast.

She went up stairs with

footsteps fleet,

And placed the candle nigh,

And grandma from her

slumbers sweet,

Was not awaked thereby.

Her night cap on her brow

she brings,

Puts off her creaking shoes,

But knotted were her apron

strings,

Beyond her power to loose.

As she to break them oft

essayed,

(No scissors were in view,)

The foolish thought came

o'er the maid,

That she could burn them through.

So to the candle's blaze she

brings

The knotted tape with speed,

Then seized the parted

burning strings,

To put them out with heed.

Then laid her down, and deep

repose

O'ercame her senses quite;

Such sleep as guileless

childhood knows,

Was Mary Ann's that night.

But ere the warning clock

had spoke,

With twelve repeated sounds,

Grandmother woke, and

stifling smoke

And smell of fire surrounds.

She waked the child, she

sought the stair,

She called each inmates

name;

The opened door let in the

air,

And fiercely rose the flame.

Up came the frighted

household band,

And pails of water threw,

But scarce, though laboured

every hand,

Could they the fire subdue.

This done at length, the

chamber shew'd

A mass of mud and cinder,

For many a garment stout and

good,

Was that night burnt to tinder.

Poor Mary's apron, frock and

all,

Had helped the fire to feed,

And woefully did she recall

Her own incautious deed.

And had she slept that night

alone,

Her usual situation,

The pangs of death she sure

had known,

By fire or suffocation

The lesson Mary ne'er

forgot,

While she on earth existed,

And never after burned a knot,

Howe'er it might be twisted.

Grandmother lived to go

abroad,

And make this full relation,

And telling, humbly thanked

the Lord

For Mary's preservation.

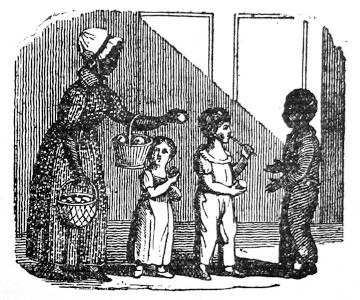

GOOD HEARTED NANCY

With so many children

surrounded,

And when she can make for

them candy and cake,

Her pleasure is almost

unbounded.

O Robert can tell, for she

loves him so well,

And sends for him many a

day;

'Tis Nancy, whose joy is to

have this dear boy,

Come in her clean kitchen to

play.

Though dark is her face, of

the African race,

She is a most kind hearted

creature,

For 'tis well understood,

that all can be good,

Though diff'rent in color

and feature.

It was one pleasant summer

morn,

Soon after day began to

dawn,

Before the brilliant sun

arose,

Or children woke from sweet

repose;

When near the shore, upon a

green

Were many people to be seen,

Why do they thus assemble

round?

Alas! a little boy is

drown'd,

It was a little Irish boy,

His parent's only pride and

joy;

And they had sought for him

all night,

Nor found him until morning

light;

When his poor mother was the

one

To find her little lifeless

son,

She saw him in a watery bed,

With no soft pillow for his

head,

And O, she scream'd with

sorrow wild,

When thus she found her

darling child,

When craz'd with grief the

father ran,

All piti'd the poor frantic

man;

'Twas then the wife subdued

her grief,

And strove to give him some

relief.

The father's arms his child

enfold,

Tho' it was wet, and stiff,

and cold;

When on the grass his son he

laid,

The mother knelt beside and

pray'd,

But ah, her prayers were all

in vain

To call his spirit back

again:

Perhaps she pray'd for

strength to be

Resign'd to His all-wise

decree,

Who took the treasure He had

given,

That they might look for it

in heaven—

And hope to meet his spirit

there

When they should quit this

world of care.

Who morn and eve is sure to

come,

And drive the cows from

pasture home,

When milk'd, he drives them

down again,

Through scorching heat, or

wind, or rain;

And ne'er neglects his sole

employ,—

Alas! 'tis a poor Idiot Boy.

He seems more happy than a

king,

As tho' in want of no one

thing;

And as he passes thro' the

streets,

He smiles at every one he

meets:

No sorrow e'er disturbs the

joy

Of this poor harmless Idiot

Boy.

Unconscious of his humble

lot,

The wisest head he envies

not;

And children who with sense

are blest,

Should never dare this boy

molest,

Or ever any way annoy

This inoffensive Idiot Boy.

"Dear Aunt," one

evening Thomas said,

"Of all the stories you

have read,

I pray you tell me one;

But not of people old or

sick,

Or naughty boys, but tell me

quick

Some dog, or cat, or monkey's trick,

That made a deal of

fun!"

Now to this Aunt, full many

a rhyme

And story of the olden time,

Had oft been said or sung;

She paus'd a while, the fire

she stirr'd,

And then repeated word for

word,

This tale, which she in

prose had heard,

When she was very young.

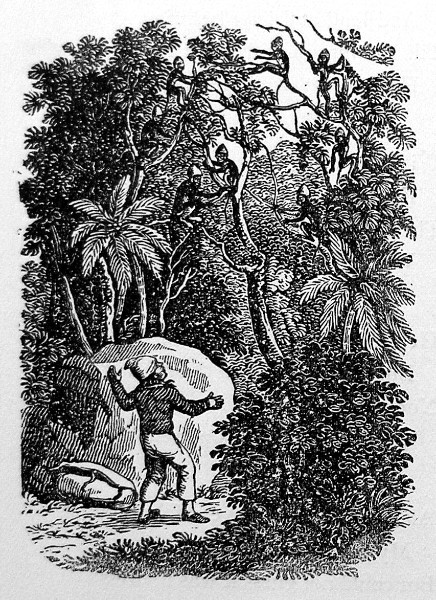

THE SAILOR AND THE MONKEYS

Once, in the hope of honest

gain,

From Afric's golden store,

A brisk young sailor cross'd

the main

And landed on her shore.

And leaving soon the sultry

strand,

Where his fair vessel lay,

He travell'd o'er the

neighboring land,

To trade in peaceful way.

Full many a toy had he to

sell,

And caps of scarlet dye,

All such things as he knew

full well,

Would please the native's eye.

But as he travell'd through

the woods,

He long'd to take a nap,

And opening there his pack

of goods,

Took out a scarlet cap.

And drew it on his head,

thereby

To shield him from the sun,

Then soundly slept, nor

thought an eye

Had seen what he had done.

But many a monkey dwelling

there,

Though hidden from his view,

Had closely watched the whole affair,

And long'd to do so too.

And while he slept did each

one seize

A cap to deck his brows,

Then climbing up the highest

trees,

Sat chattering on the boughs.

The sailor wak'd, his caps

were gone,

And loud and long he

grieves,

Till looking up with heart forlorn,

He spied at once the

thieves.

With cap of red upon each

head,

Full fifty faces grim,

The sailor sees amid the

trees,

With eyes all fix'd on him.

He brandish'd quick a mighty

stick,

But could not reach their

bower,

Nor yet could stone, for

every one

Was far beyond his power.

Alas! he thought, I've

safely brought

My caps far over seas,

But could not guess it was

to dress

Such little rogues as these.

Then quickly down he threw

his own,

And loud in anger cri'd,

Take this one too, you

thievish crew,

Since you have all beside.

But quick as thought the

caps were caught

From every monkey's crown,

And like himself, each

little elf

Threw his directly down

He then with ease did gather

these,

And in his pack did bind,

Then through the woods

convey'd his goods,

And sold them to his mind.

THE INDIAN AND THE BASKET*

Among Rhode Island's early

sons,

Was one whose orchards fair,

By plenteous and

well-flavoured fruit,

Rewarded all his care.

For household use they

stored the best,

And all the rest conveyed

To neighboring mill, were

ground and press'd,

And into cider made.

The wandering Indian oft

partook

The generous farmer's cheer;

He liked his food, but better still

His cider fine and clear.

And as he quaff'd the

pleasant draught,

The kitchen fire before,

He long'd for some to carry

home,

And asked for more and more.

The farmer saw a basket new

Beside the Indian bold,

And smiling said, "I'll

give to you

"As much as that will hold."

Both laugh'd, for how could

liquid thing

Within a basket stay;

But yet the lest

unanswering,

The Indian went his way.

When next from rest the

farmer sprung,

So very cold the morn,

The icicles like diamonds

hung,

On every spray and thorn.

The brook that babbl'd by

his door,

Was deep, and clear, and

strong,

And yet unfetter'd by the

frost,

Leap'd merrily along.

The self-same Indian by this

brook

The astonish'd farmer sees;

He laid his basket in the stream,

Then hung it up to freeze.

And by this process oft

renewed,

The basket soon became

A well glazed vessel, tight

and good,

Of most capacious frame.

The door he entered

speedily,

And claim'd the promis'd

boon,

The farmer laughing

heartily,

Fulfilled his promise soon.

Up to the basket's brim he

saw

The sparkling cider rise,

And to rejoice his absent

squaw,

He bore away the prize.

Long lived the good man at

the farm,

The house is standing still,

And still leaps merrily

along,

The much diminish'd rill.

And his descendants still

remain,

And tell to those who ask it,

The story they have often heard,

About the Indian's basket.

* The danger of the drink

habit was not realized in that day.

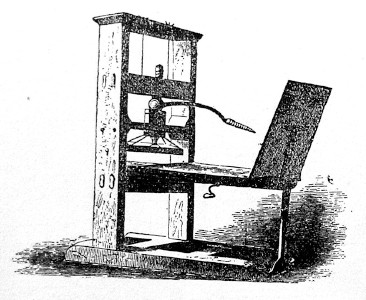

The picture reminds us that

when this book was written there were no steel pens to write with. Every

teacher then must have a penknife and know how to make pens for his pupils out

of goosequills. There are many persons still living who learned how to write

with a quill pen. In those days it was a familiar sound in the schoolroom.

"Teacher, please to mend my pen."

THE STAGE

To carry folks from place to

place;

When people only ride for

pleasure,

They choose to go more at

their leisure,

Though when they go to see

their friends,

Care not how soon their

journey ends,

Horses many miles can go,

They are so very strong;

But sometimes they will

weary grow,

And slowly move along:

Then drivers change them at

a stable,

For those that are more

strong and able,

On Sabbath-days the horse is

seen

Unshackled on the meadow

green,

THE MILL

That stands so high up on

the hill,

And listen to the pleasing

sound,

When the wind blows the

sails around.

The farmer's boy will early

rise,

Before the sun ascends the

skies,

And mounting on old Dobbin's

back,

He takes to mill the great

corn sack;

As carelessly he jogs along,

We often hear his merry

song.

Who would not be a farmer's

boy,

In such an honest safe

employ!

His bag of corn the miller

takes,

And all into the hopper

shakes,

Which comes out meal both

fine and sweet,

To make good bread for all

to eat.

IDLE GEORGE

Who neither lov'd to read or

work,

And nothing would he do all

day,

But saunter through the

streets and play,

And sleep in stables on the

hay,

Till to the work-house he

was sent,

Where quite reluctantly he

went;

And many a one was glad the

day

That lazy George was sent

away.

For well they knew that he

must mind

His master, who was good and

kind,

But now his father hears with

joy,

That he's a good industrious

boy.

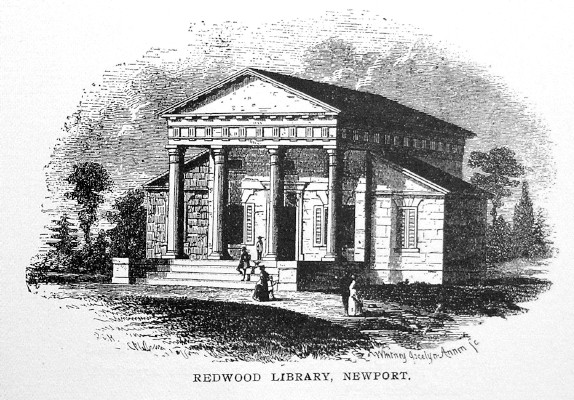

REDWOOD LIBRARY, NEWPORT.

JAMES FRANKLIN'S PRINTING

PRESS.

A REMINISCENCE

By M. C. W.

Some wee little girls, 'twas

a long time ago,

Were very desirous of

learning to sew,

Or perhaps they thought they

already knew

As such very small

dressmakers often do.

That the dolls needed

garments was real to them,

There were seams to sew up

and borders to hem,

One trouble they had in

their doll sewing play;

The needles they used went

so often astray.

And those that were bent or

too crooked to use

Were thought just as well

for the children to lose,

And that sort, we have

heard, with care were laid by,

That the little ones,

always, might have a supply.

But the stock got exhausted,

all the needles were straight,

And it would likely for

more, be a long while to wait,

A sorry time, to be sure, it

must have been,

To have their work stop,

just for one little thing.

Well, in this dilemma it

still is told,

For, as I have said, the

story is old,

Little Julia, more

thoughtful than all the rest,

It seems, went to her mother

with this request:

That the first time she

drove to town for more

Of other things, she would

go to the store

Where they sold crooked

needles; dear innocent face!

"The crooked needle

store," she said, was the place.

This artless appeal, as we

all might expect,

Touched a tender chord that

had its effect,

For a crookedT needle she

had not to wait,

But went back to her play

with one that was straight.

'Tis pleasant in a little

boat,

To sail when winds are mild;

But who would wish to be

afloat,

When storms are raging wild.

And little boys should never

dare

To sail in one alone,

For all who do not sail with

care,

Are in the water thrown,

But men can manage them with

ease,

And sail large ships across

the seas,

Some men delight to sail

away,

And visit distant lands,

While others choose at home

to stay

And labour with their hands,

There is a Power above can

keep,

Mankind from danger on the

deep.

|