| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2015 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

|

CHAPTER IX OMEI SHAN, THE SACRED The rose-red

city of Chia-ting lives in my memory as a vision of

beauty, the most charming (at a distance) of the many charming (always at a

distance) Chinese towns that I have seen. Built on a sandstone ledge at the

junction of the Ta Tu and Ya with the Min, its crenellated red walls rise

almost directly from the water, which, when in flood, dashes high against the

foundations. On the northwest the city rises to nearly three hundred feet above

the level, and standing on the wall one looks down upon a sea of living green

from which rise temple and pagoda, or west across Chia-ting plain, perhaps the

loveliest and most fertile spot in the Chinese Eden, and then farther west

still to where on the horizon towers Omei Shan, the Holy of Holies of Buddhist

China, often, alas, shrouded in mist from base to summit, for this is a land of

clouds and rain and floods. Looking across the river to the great cliffs opposite

the town, one discerns dimly, carved on the face of the rock, the wonder of the

region, a colossal Buddha more than three hundred feet in height, sitting

serenely with his hands on his knees, and his feet, or what ought to be his

feet, laved by the rushing water of the Ta Fo Rapid.

As the tale runs, this was the work of a good monk of the eighth century, who

spent his life over the undertaking in the hope that by this pious act he might

avert the terrible floods that devastated the region. A mighty task boldly

conceived and patiently carried out, but still the rain pours down, and still

the rivers rise and drown the land. Baber tells the dramatic story of one of the greatest

of the floods. It occurred in 1786 when the fall of a cliff in the Ta Tu dammed

the river completely for a time. Warnings were sent to the villages along the

banks, and many fled to the hills, but the people of Chia-ting, trusting to

their open plain over which the water could spread itself, scouted the warning,

and the cry, "Shui lai-la" ("The water is coming"), became

the catchword of the hour. Let Baber tell the rest: — "It was holiday in Chia-ting some days after the

receipt of the notice, and the light hearted crowds which gathered on such

occasions were chiefly attracted by a theatrical representation on the flat by

the water-side. One of the actors suddenly stopped in the middle of his rôle,

and gazing up the river, screamed out the now familiar by-word, 'Shui lai-la!'

This repetition of the stock jest, with well-simulated terror, as it seemed to

the merry-makers, drew shouts of laughter; but the echoes of the laugh were

drowned in the roar of a deluge. I was told how the gleeful

faces turned to horror as the flood swept on like a moving wall, and

overwhelmed twelve thousand souls." While in Chia-ting I crossed the river one day to see

the great Buddha from near by, but it is very difficult to get a good view of

the image. The river runs at the foot of the cliff at such a rate that it was

all the boatmen could do to keep us off the rocks, and looking down from above,

the overhanging shrubs and grasses almost hide it from sight. There is an interesting

monastery on the summit of the hill, called the "Monastery of the Voice of

the Waters." Here I spent a delightful hour wandering through the

neglected garden and looking over the treasures of the place, a rather

remarkable collection of drawings and inscriptions engraved on slate, the work

of distinguished visitors of past times, some dating back even to the Sung

period. There were landscapes extremely well done, others were merely a flower

or branch of a blooming shrub, but all bore some classic quotation in

ornamental Chinese character. I bought of the priest for a dollar a bundle of

really fine rubbings of these engravings. At another monastery a gallery full

of images of the "Lo-han," the worthiest of Buddha's disciples, was

being tidied up. The variety of pose and expression in these fifty-odd

life-size images was extraordinary, and some of them were wonderfully good, but

the workmen handled them without respect as they

cleaned and painted. It is a Chinese proverb that says, "The image-maker does

not worship the gods; he knows what they are made of." There is one drawback to the delights of Chia-ting,

and that is the climate. To live and work in the damp heat that prevails much

of the time must test the strength, and I imagine the Europeans stationed here

find it so. Chia-ting boasts two strong Protestant missions, American Baptist

and Canadian Methodist, well equipped with schools and a hospital, and they are

hard at work making Chia-ting over, body and soul. At the time of my visit they

were engaged in a strenuous contest with the representatives of the British

American Tobacco Company, and both sides were placarding the town with posters

setting forth the evils or the benefits of cigarette-smoking. Chia-ting is the great point of departure for Mount

Omei, thirty miles away, and I stayed only long enough to rearrange my kit and

hire coolies for the trip. Again I had a chance to see the strength that the

Chinese have through organization. Each quarter of Chia-ting has its coolie

hong, and woe betide you if you fall out with your own; you will have

difficulty in getting served elsewhere. Fortunately my host was on good terms

with his proper hong, and after a good-humored, long-drawn-out discussion I

secured the men I wanted. It was raining when we started from Chia-ting and it kept on all day. Nevertheless, as soon as I was

outside the West Gate of the city I exchanged my closed chair for one specially

devised for the mountain climb, simply a bamboo chair furnished with a swinging

board for a foot-rest. It gave of course no protection against sun or rain, but

there was nothing to cut off the view. The closed chair affected by the Chinese

seemed to me intolerable, a stuffy box half closed in front, and with mere

loopholes on the sides. But fifteen years ago no European woman could ride in

anything else without danger of being mobbed. All the first day we were crossing the beautiful

Chia-ting plain, seamed and watered by many rivers and streams. The path wound

in and out among splendid fields of maize and fine fruit orchards, and the

comfortable looking villages were densely shaded with oak and mulberry trees.

It ought to be a prosperous district, for not only is it rich in natural

resources, but the throngs of pilgrims that pass through here on their way to

the Sacred Mountain must bring a lot of money into the towns. At the start we kept above the Ta Tu, but later we

crossed the Ya, now a strong-flowing tranquil river, and farther along still at

the little town of Süchi ("Joyous Stream"), famous for its silk, we

came to the Omei, which has its sources on the lower slopes of the Great

Mountain. After this the country was more broken, but everywhere there was the

same careful cultivation, and on all sides we heard

the plash of falling water and the soft whirr of the great Persian wheels

busily at work bringing water to the thirsty land; and occasionally we saw men

working with the foot a smaller wheel by which the next higher levels were

irrigated. Chen Chia Ch'ang, a small market-town a few miles

east of Omei-hsien, made a charming picture, its walls shining white against

the dark background of the mountain as we approached it across the green

rice-fields. Entering its broad, crowded street we found a theatrical

performance going on in an open hall opposite the temple. While my coolies were

drinking tea I joined the crowd in front of the stage, which was raised several

feet above the street. The play, which was in honour of the village idol, was

beyond my comprehension, but the pantomime of the actors was very good. This

sort of thing is dearly liked by the Chinese. The players are usually

maintained by the village, and a good deal of the unpopularity of the Christian

converts arises, I am told, from their unwillingness to contribute because of

the so-called idolatrous character of the performance. The town of Omei where we spent the night seems to

exist chiefly for the sake of the thousands of pilgrims who make a last halt

here before they begin the ascent of the mountain. Mindful of the many Tibetans

who pass through here in the spring, I made a raid

upon the shops, but in vain; all that I found was two good pieces of Chinese

bronze. The owner and I could not agree on a price, so I left him to think it

over until I came by again, and then he was away and his wife did not dare

unlock his cases, although I offered her what he had asked. The rain poured

down, but a crowd gathered to offer sympathy and suggestions, while my men and

I argued with her. Would she not fare worse if her husband found she had missed

a sale than if she disobeyed orders? All to no purpose, so I went away

empty-handed. That evening it rained brass pots, but alas, nothing that I

wanted. Usually in these small places the woman seems a very

active member of the establishment, and I am told that a man often wishes to

consult his wife before making a large deal. The Chinese woman, perhaps, lacks

the charm of the Japanese or Indian, but in spite of her many handicaps she

impresses the outsider with her native good sense and forcefulness, and I should

expect that even more than the other two she would play a great part in the

development of her people when her chance came. It was again raining when we started the next

morning; indeed, it seemed a long time since I had felt really dry, but the

grey day harmonized perfectly with the soft English beauty of the country that

lies between Omei-hsien and the foot of the mountain, wooded

lanes and glens, little brooks rippling between flowery banks, fine stone

bridges spanning the swift green Omei, red temples overhung by splendid banyan

trees, and over all the dark mysterious mountain, lifting its crown ten

thousand feet above our heads. Did ever pilgrim tread a more beautiful path to

the Delectable Mountains? And there were so many pilgrims, men and women, all

clad in their best, and with the joy of a holiday shining in their faces. There

were few children, but some quite old people, and many were women hobbling

pluckily along on their tiny feet; the majority, however, were young men,

chosen perhaps as the most able to perform the duty for the whole family. They

seemed mostly of a comfortable farmer class; the very poor cannot afford the

journey; and as for the rich — does wealth ever go on a pilgrimage nowadays?

All carried on the back a yellow bag (yellow is Buddha's colour) containing

bundles of tapers to burn before the shrines, and in their girdles were strings

of cash to pay their way; priests and beggars alike must be appeased. After an hour or so we left behind the cultivation of

the valley, and entered the wild gorge of the Omei, and after this our path led

upwards through fine forests of ash and oak and pine. The road grew steeper and

steeper, often just a rough staircase of several hundred steps, over which we

slipped and scrambled. Rain dripped from the branches, brooks dashed down the mountain-side. We had left behind the

great heat of the plain, but within the walls of the forest the air was warm

and heavy. But nothing could damp the ardour of the pilgrim horde. A few were

in chairs; I had long since jumped out of mine, although as Liu complained,

"Why does the Ku Niang hire one if she will not use it?" He dearly

loved his ease, but had scruples about riding if I walked, or perhaps his

bearers had. Some of the wayfarers, old men and women, were carried pick-a-back

on a board seat fastened to the coolie's shoulders. It looked horribly insecure

and I much preferred trusting to my own feet, but after all I never saw an

accident, while I fell many times coming down the mountain. The beginnings of Mount Omei's story go back to the

days before writing was, and of myth and legend there is a great store, and

naturally enough. This marvel of beauty and grandeur rising stark from the

plain must have filled the man of the lowlands with awe and fear, and his fancy

would readily people these inaccessible heights and gloomy forests with the

marvels of primitive imagination. On the north the mountain rises by gentle

wooded slopes to a height of nearly ten thousand feet above the plain, while on

the south the summit ends in a tremendous precipice almost a mile up and down

as though slashed off by the sword of a Titan. Perhaps in earliest times the Lolos worshipped here, and the mountain still figures in their legends.

But Chinese tradition goes back four thousand years when pious hermits made

their home on Omei. And there is a story of how the Yellow Emperor, seeking

immortality, came to one of them. But Buddha now reigns supreme on Omei; of all

the many temples, one only is Taoist. According to the legend, at the very

beginning of Buddhist influence in China, P'u-hsien Bodhisattva revealed

himself to a wandering official in that wonderful thing known as "Buddha's

Glory," and from this time on, Mount Omei became the centre from which the

light of Buddhist teaching was spread abroad over the entire country. The land now belongs to the Church, and there are not

many people on the mountain besides the two thousand monks scattered about in

the different monasteries which occupy every point where a flat spur or

buttress offers a foothold. Each has its objects of interest or veneration, and

I believe that to do one's duty by Omei, one must burn offerings before

sixty-two shrines. Judging by the determined look on some of the pilgrims'

faces, they were bent on making the grand tour in the shortest time possible;

in fact, they almost raced up the breakneck staircases. To save expense, some

make the whole ascent of one hundred and twenty li from Omei-hsien in a day.

Even women on their bound feet sometimes do this, I am told. I would not

believe it on any authority had I not seen for

myself the tramps these poor crippled creatures often take. As I was in no hurry, we stopped for the night at

Wan-nien Ssu, or the "Monastery of Ten Thousand Years," one of the

largest on the mountain and with a recorded history that goes back more than

fifteen hundred years. We were made very welcome, for the days have passed when

foreigners were turned from the door. Their patronage is eagerly sought and

also their contributions. After inspecting our quarters, which opened out of an

inner court and were spacious and fairly clean, I started out at once to see

the sights of the place, for daylight dies early in these dense woods. Like all

the rest Wan-nien Ssu is plainly built of timbers, and cannot compare with the

picturesque curly-roofed buildings one sees in the plains below. Indeed, it

reminded me of the Tibetan lamasseries about Tachienlu, and it is true that

thousands of Tibetans find their way hither each spring, and the hillsides

reëcho their mystic spell, "Om mani padme hum," only less often than

the Chinese, "Omi to fo." Behind the building where I was quartered is another,

forming part of the same monastery, and within is concealed rather than

displayed the treasure of the place, and indeed the most wonderful monument on

the mountain, a huge image of P'u-hsien enthroned on the back of a life-size

elephant, all admirably cast in bronze. Although dating from the ninth century, the wonderful creation remained unknown to the

"outside barbarian" until Baber came this way a generation ago. He

speaks of it as probably the "most ancient bronze casting of any great

size in existence." It is a sad pity that no one has succeeded in getting

a good picture of this notable work, but not merely is it railed about with a

stone palisade, but the whole is enclosed in a small building of heavy brick

and masonry with walls twelve feet thick, which secure it against wind and

rain, but also keep out most of the light. Wan-nien Ssu boasts another treasure more readily displayed,

a so-called tooth of Buddha weighing about eighteen pounds. The simple pilgrims

looked on reverently as the priests held it before me, but the latter had a

knowing look when I expressed my wonder at the stature of the being who had

teeth of such size. Probably they knew as well as I that it was an elephant's

molar, but they were not above playing on the credulity of the ignorant folk. Out of respect for the feelings of the monks I had

brought up no fresh meat, and of course there is none to be obtained on the

mountain, so I dined rather meagrely. Although the people generally do not

hesitate to eat meat when they can get it, the priests hold stiffly to the

Buddhist discipline which forbids the taking of life, and it is only

unwillingly that they have acquiesced in foreigners' bringing meat into the monastic precincts or even onto the mountain. But at

least they did their best to make good any lack by sending in dishes of Chinese

sweetmeats, candied seeds, ginger, dried fruits. After dinner one of the

younger priests sat for a long time by my brazier, amusing himself with Jack,

the like of whom he had never seen before, and asking many simple questions.

What was I writing? How did I live? Where would I go when I went away? Where

was my husband? — the same questions asked everywhere by the untutored, be it

in the mountains of Kentucky or on the sacred heights of Mount Omei. On leaving the next morning the "Yuan-pu,"

or "Subscription Book of the Temple," a substantial volume in which

one writes one's name and donation, was duly put before me. Being warned

beforehand I knew what to give, and I was not to be moved even though my

attention was called to much larger sums given by other visitors; but I had

also been told of the trick practised here of altering the figures as served

their purpose, so I was not moved even by this appeal. The next day brought us to the summit after a

wearying pull up interminable rock staircases as steep as the steepest attic

stairs, and hundreds of feet high. Most of the time we were in thick woods,

only occasionally coming out into a little clearing, but even when the trees

fell away, and there ought to have been a view,

nothing was to be seen, for the thick mists shut out all above and below. We

passed by innumerable monasteries, most of them looking prosperous and well

patronized; they must reap a rich harvest in cash from the countless pilgrims.

Everywhere building was going on, indicating hopeful fortunes, or, more likely,

recent disaster, for it is the prevailing dampness alone that saves the whole

mountain-side from being swept by fires, and they are all too frequent as it

is. It is one of the many topsy-turvy things in

topsy-turvy China that this prosaic people is so addicted to picturesque and

significant terms. I found the names of some of the monasteries quite as

interesting as anything else about them. From the "Pinnacle of

Contemplation" you ascend to the "Monastery of the White

Clouds," stopping to rest in the "Hall of the Tranquil Heart,"

and passing the "Gate to Heaven" you enter the "Monastery of

Everlasting Joy." Toward the summit the forest dwindled until there was

little save scrub pine and oak, a kind of dwarf bamboo, and masses of

rhododendron. At last we came out into a large clearing just as the sun burst

from the clouds, lighting up the gilded ball that surmounts the monastery where

I hoped to find shelter, the Chin Tien, or "Golden Hall of the True

Summit," a group of low timbered buildings, quite without

architectural pretensions. Entering the open doorway I faced a large shrine

before which worshippers were bending undisturbed by our noisy entrance. Stairs

on either hand of the shrine led to a large grassy court surrounded on all four

sides by one-story buildings, connected by a broad corridor or verandah, and

back of this, steep steps led to a temple perched on the very edge of the great

cliff. A young priest came to meet me and very courteously

showed me the guest-rooms, allowing me to choose two in the most retired

corner, one for myself and another for the interpreter and cook, while the

coolies found comfortable quarters near by. View there was none, for my room,

though adorned with real glazed windows, looked out on a steep bank, but at

least it had an outside door through which I might come and go at will. The

furniture was of the usual sort, only in better condition than ordinarily;

heavy beds, chairs, tables, but everything was surprisingly clean and

sweet-smelling. Here in this Buddhist monastery on the lofty summit

of China's most sacred mountain I spent three peaceful days, happy in having a

part in the simple life about me. Chin Tien is one of the largest and most

prosperous of Omei's monasteries, and it is also one of the best conducted.

Everything was orderly and quiet. Discipline seemed well maintained, and there

was no unseemly begging for contributions as at

Wan-nien Ssu. It boasts an abbot and some twenty-five full-fledged monks and

acolytes. All day long pilgrims, lay and monastic, were coming and going, and

the little bell that is rung to warn the god of the presence of a worshipper

tinkled incessantly. Some were monks who had come long distances, perhaps from

farthermost Tibet, making the great pilgrimage to "gain merit" for

themselves and for their monastery. Many of the houses on Omei gave to these

visitors crude maps or plans of the mountain, duly stamped with the monastery

seal, as proof that the journey had been made, and on my departure one such,

properly sealed with the Chin Tien stamp, was given to me. One day was like another, and all were peaceful and

full of interest. I expect the weather was as good as one could look for at

this season of the year; although the mists rolled in early in the forenoon

shutting out the plain, yet there was little rain, and the night and dawn were

glorious. Each morning I was out before sunrise, and standing on the steps of

the upper temple saw the whole western horizon revealed before my enchanted

eyes. A hundred miles away stretched the long line of the Tibetan snow-peaks,

their tops piercing the sky. It seemed but a step from earth to heaven, and how

many turn away from the wonderful sight to take that step. Two strides back and

you are standing awestruck on the edge of the

stupendous precipice. The fascination of the place is overpowering, whether you

gaze straight down into the black depths or whether the mists, rolling up like

great waves of foam, woo you gently to certain death. No wonder the place is

called "The Rejection of the Body," and that men and women longing to

free themselves from the weary Wheel of Life, seek the "Peace of the Great

Release" with one wild leap into the abyss below. At every hour of the day pilgrims were standing at

the railed-in edge of the cliff, straining their eyes to see into the uttermost

depths below, or looking skywards for a sight of "Buddha's Glory,"

that strange phenomenon which has never been quite explained; it may be akin to

the Spectre of the Brocken, but to the devout Buddhist pilgrim it is the

crowning marvel of Mount Omei. Looking off to the north and east one saw stretched

out, nearly ten thousand feet below, the green plains and silver rivers of

Szechuan. Southward rose the black peaks and ranges of Lololand, buttressed on

the north by the great, table-shaped Wa Shan, second only to Omei in height and

sacredness. Before the first day was past every one had become

accustomed to my presence, and I attracted no attention as I came and went. My

wants were looked after, and one or the other of the little acolytes spent many

hours in my room, tending the fire in the brazier, or playing with Jack, or

munching the sweetmeats with which I was kept supplied. They were nice little

lads and did not bother me, and rarely did any one else disturb my quiet; it

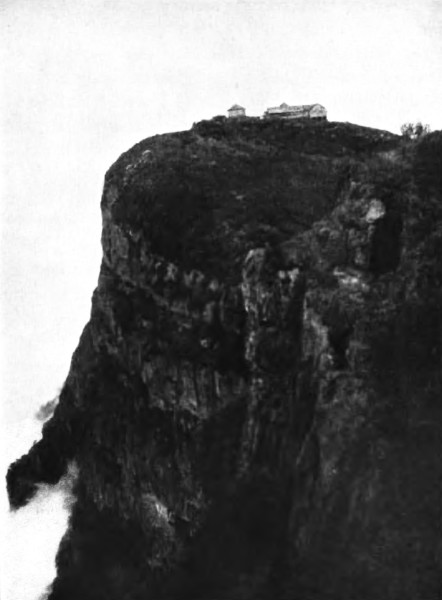

was such a comfort after the living in public of the last month.  THE "REJECTION OF THE BODY" Cliff a mile high. Mount Omei, West Szechuan The second morning of my stay I attended an early service in the lower temple near my room. Some

twelve monks took part; one, the abbot, was a large, fine-looking man, and all

had rather agreeable faces, quite unlike the brutal, vicious look of the lamas

of Tachienlu. There was much that recalled the ritual of the Roman Catholic Church,

— processions, genuflexions, chanting, burning of incense, lighting of candles,

tinkling of bells, — all centring round a great figure of Sakyamuni. The words

I could not understand, but the reverent expression on the monks' faces, their

orderly bearing as they circled slowly round, keeping always the bared right

shoulder toward the image, made the service very impressive in spite of the

pranks of the little acolytes and the loud talk of passing men and women. In turn I visited the near-by temples, but few were

of any special interest. The hilltop has been burnt over several times, the

last time within a generation, and all the buildings on the summit are of

recent date. The most famous of all, the great bronze temple dating from the

fifteenth century, which after being struck by lightning several times was

finally destroyed, has never been restored, thus

giving the lie to the popular belief that what the lightning destroys the gods

will replace. The fragments of castings that are left are really fine, and it

is a marvel how they ever were brought from Chengtu where they were made, for

many are of great weight. A little below the trail by which we came was the

pewter-roofed monastery, very appropriate here, as pewter is the only metal the

Buddhist pilgrim is supposed to use or possess. But after all, the charm of the place lay not in this

or that building or relic, but in the beauty of the surroundings and in the

peace of spirit that seemed to abide here. No need to cast one's self over the

precipice to secure freedom from the body. Here on the high mountain-top among

these simple minds, the cares and bothers of the life of the plain seemed to

fall off. If I came as a sight-seer I went away in the mood of a pilgrim.

Turning my back upon the crowded paths I spent long hours of quiet under the

pines on the western slope, facing always toward the mountains. Sometimes the

clouds concealed them wholly, at other times just one peak emerged, and then

perhaps for a moment the mists rolled away, and the whole snowy line stood

revealed like the ramparts of a great city, the city of God. And the best of all was not the day, but the night.

The monastery went early to bed, and by ten o'clock bells

had ceased to ring, the lights were out. Then came my time. Slipping out of my

room I stole up the slope to the overhanging brow of the cliff. The wind had

died down, the birds were still, not a sound broke the great silence. At my

feet were the depths, to the west rose height on height, and on all lay the

white light of the moon. Close by hundreds of weary pilgrims were sleeping

heavily on their hard beds. Day after day and year after year they climbed

these steeps seeking peace and help, pinning their hopes to burning joss stick

and tinkling bell and mystic words, and in Western lands were other pilgrims

entangled likewise in the mazes of dogma and form. But here among the stars, in

the empty, soundless space of the white night, the gods that man has created

seemed to vanish, and there stood out clear the hope that when time has ceased,

— When all the faiths have passed; Perhaps, from darkening incense freed, God may emerge at last." Finally the day came when I was forced to turn away

from the miracles of Omei. Our stores were almost gone, and the coolies had

burnt their last joss sticks; so I took farewell of the kindly monks of Chin

Tien and started down the mountain. The sun shone as we set off, but as we

descended, the clouds gathered and the rain fell in torrents. Each steep, straight staircase was a snare to our feet. Sprawling and

slithering we made our way down. No one escaped, and the woods resounded with

gay cries, "Have a care, Omi to fo! Hold on tight, Omi to fo! Now, go

ahead, Omi to fo!" There was no going slowly, you stood still or went with

a rush. Women tottering along on crippled feet pointed cheerily at my big

shoes. I dare say the difference in size consoled them for all their aches and

pains. It was almost dark when we reached Omei-hsien, soaked

to the skin. I had a big fire made for the coolies and we all gathered round in

companionable fashion for the last time. The return journey the next day across

the plain was as charming as ever, but the steamy heat of the low level was

very depressing, and we were all glad to take to a boat for the last twenty-two

li. I had one more day in Chia-ting, visiting one or two

temples and making the last arrangements for the trip down the river to

Chung-king. Wisely helped by one of the American missionaries I secured a very

comfortable wu-pan, for which I paid twenty-five dollars Mexican. It was well

fitted out, and equipped with a crew of seven, including the captain's wife,

and a small dog known as the "tailless one." We started down the

river late in the afternoon. There was just time for one look at the Great

Buddha as the current hurled us almost under his feet,

then a last glance at the beautiful town, all rose and green, and a wonderful

chapter in my journeying had come to an end. Only three months later and

Chia-ting was aflame with the fires of revolution, for it was the first city in

all Szechuan to declare for the Republic, and there was many a fierce contest

in its narrow, winding streets. |