| Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2004 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to Florida Trails Content Page Click Here to return to last Chapter |

(HOME) |

| Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2004 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to Florida Trails Content Page Click Here to return to last Chapter |

(HOME) |

|

CHAPTER

VIII

CHRISTMAS AT ST. AUGUSTINE Whoever has since discovered the North Pole, we know that Santa Claus was the original settler and, to whatever land he may come, we think of him as cheering his reindeer on over new fallen snow. Nor was frost to be denied him here in St. Augustine where many people believe perpetual summer reigns. The red-nosed morning sun looked forth in some indignation on fields white with it, palm trees crisp, and broad banana leaves wilted black under its keen touch. The gentle breeze that drifted in from the north had ice in its touch and I do not know how the roses that held up pink petals bravely and tossed their soft, tea scent over the garden fences stood it without wilting. Most of them are planted near shelter, which may account for it. But the tea roses are essentially the ladies of their kind. They seem to have the feminine trait of exposing pink and white beauty to the inclement winds without growing goose flesh upon it. They stand brave and unconcerned in an atmosphere where mere men and vegetables wilt, frostbitten. The day after Christmas brought a stiff wind from the northwest, a wind that fainted from its own rage during the night and left us for a few morning hours a temperature of twenty-six degrees. This is somewhat disconcerting to muslin-clad migrants. Christmas came flying overseas to the quaint old town by way of the long levels of Anastasia Island, which bars off the real ocean to the eastward. Here I fancy Santa Claus landing for a moment to re-arrange his pack before getting down chimney to business, and here he might well feel at home on South Beach. Nowhere has nature more closely simulated snowdrifts. The dazzling white sand is as fine grained as any blown snow of a Canadian winter, and the north wind sent it drifting down leagues of coast where it piled in hillocks that grow with one shift of wind and shrink with the next. I had but to shut my eyes and listen to the silky susurrus of these tiny crystals one upon another to hear the same song that the New England pastures sing of a bright day in January when the snow is deep and a zero wind steals froth the top of one drift to build bastions and frost fortifications on another. With closed eyes the sibillant song was the fairy tenor to the bass of the surf which was a memory of the roar of white pines, tossing in the gale. I had but to open my eyes and see these white, scurrying films of sandsnow to think myself really once more in Massachusetts. Inland the pale drifts whelm red cedar and bayberry outposts of the forests that are as flat-topped and wind-crippled as any shrubs that hold the outer defenses of zero-bitten, northern hilltops, moated, portcullised, with barbican and glacis in snow-mounded simulation of fortresses built by man. Surely nature had hung Christmas decorations on the forefront of St. Augustine in lavish profusion. I thought at one glance that Santa Claus himself had arrived on all this make-believe snow landscape and was resting his reindeer a moment behind the white drifts inland. I heard stamping hoofs and saw shaggy brown coats that might well be those of Prancer and Dancer, of Dunder and Blitzen. But a second look showed long ears instead of caribou antlers, and a band of the curious little half wild donkeys that roam the island trotted forth. Getting back from the roar of the surf, I began to find the Christmas decorations mingled with the warmer phase of Florida. There the sun warmed all things in sheltered hollows till it seemed as if the almanac had repented and Easter was trailing soft garments of spring through the place to soothe all winter’s ailments. Scrub palmettos lifted their heads from the sand for the moon made a broad pathway of silver light across the Matanzas River to the walls of the old coquina fort which for two hundred years was all St. Augustine, and for the matter of that, all Florida, so far as white man’s dominion went. It was easy to fancy Santa Claus pricking his coursers from the old coquina quarry on the island, along this silver road, bringing Christmas cheer to the St. Augustine of to-day. In the shadows along either side of the coruscating pathway it was easy to see other shades, the dark forms of boats loaded with stone from the quarries, with motley crews toiling at the oars, sinking beneath the tide with the painful years, and others coming to take their places; convicts from Spain and Mexico, political prisoners, Seminoles and slaves, all prodded by the relentless steel of Spain to the building of the great fort that stands almost unscarred to-day, an acme of mediaeval fort building. All night it stood in gray dignity, but the moonlight touched it lovingly and drew silver from the pathway of toil and tipped the bastions with white fire and drew gleaming edges all along the ramparts till it seemed as if the haughty inquisitions of Spain, the bluff greed of ancient England, and even the pagan myth of the good old saint of gifts were but gray memories out of which glowed a clearer light, that of that star in the east which the wise men followed. We do not know which star it is, out of the incomputable number, but every Christmas Eve it swings the blue arc of the sky and sends its white light down upon the things for which men have toiled, master and slave alike, and glorifies them. Before midnight the northern chill left the place, the wind ceased, and a sweet-aired calm fell upon all things. The rustics of old England long ago brought to New England a tale which I love to believe, that at midnight before Christmas the cattle kneel in adoration in their stalls. So in this town of strange contrasts, which is so old and so new, it seemed to me as if at midnight all nature knelt in adoration. Of what went on within palace or hovel I know little, but without the air renewed its kindly warmth and from every garden rose upon the air a gentle incense of flowers. Here poinsettias flaunted red involucres that were brave with the color of the season and there the dark green of English ivy fretted the walls with close-set leaves. Chrysanthemums held up pink and yellow and white blooms to the silver light and sent out the medicinal smell of their leaves as you brushed by them. You could not see the blue of the English violets in their dark green beds and borders, but the odor of them subtended the scent of the tea roses and the Marechal Neils climbing high on their trellises lost their yellow tint and were as white as the light that shone on them.

Tiny ferns, the southern

polypodys, which you shall hardly know from those of the north by their

appearance, seem to have little of the rock-climbing proclivities of

their northern prototypes. These love a tree. Often you will find the

level limbs of live-oaks made into ribbon borders with them and they

nestle in the crevices between the criss-crossed stubs of palmetto

leaves along the trunks whence the leaves themselves have fallen. Here

in St. Augustine they seem to love the roofs of old houses, garlanding

them with a most delicate beauty. If the northern polypody grew here I

should expect to find the crevices between the stones of the old fort

green with it and the bluff old sergeant custodian would have trouble

in keeping it from making a fairy greensward of alt slopes and levels

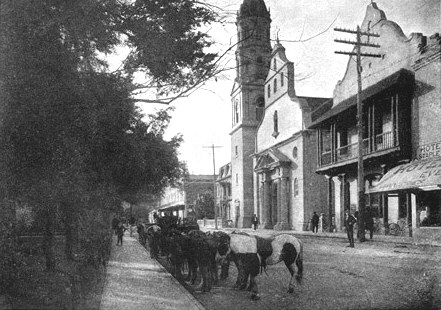

on the parapets.  “Cathedral Place, St. Augustine” The southern polypody barely touches the fort. It seems to demand wood for its rooting surface and it makes the old-time roofs lovely with its tiny pinnate fronds. I dare say every moonlit night these soft aerial gardens entangle the light and are silvered by it, but it seemed as if on this night of nights the radiance was softer and glowed with a clearer fire. Over in the new part of the town where wealth has built huge domes and pinnacled minarets and fretted the walls and arches of great stone buildings with every cunning device of the builder’s art, the gentle feet of this home-loving fern refuse to climb and walls and towers and copings and minarets seemed bare and garish in all their architectural beauty, by contrast. It was by way of such scenes as these under the round moon of midnight that Christmas day first touched St. Augustine. And yet, for all the wonder beauty of the town in this white radiance it seems to me the wonder of all lay that night within the bare walls of a northerly, long-neglected casemate of the old gray fort. The open court of the place is not unlike that of an Eastern khan. The casemate is a high-walled, bare room which opens from it, its barred window letting in a narrow rectangle of the midday sun. What gentle-souled soldier dwelt within this room in the days of Spanish domination no one can tell me, nor what lover of shady English lanes, babbling brooks and cool, mossy retreats succeeded him with the coming of the English flag to wave its St. George and St Andrew’s crosses proudly above the ramparts. Only it seems as if some lover of ferny woodlands must have dwelt there and thought long of such places, for out of the rough rock wall itself grows to-day the finest specimen of Venus’ hair fern I have ever seen, its cool, translucent, beautifully lobed pinnules dripping from fronds of rich beauty that form a soft green cradle on the floor and pillow their pure sweetness against the wall itself. It may be that some conscripted Spanish peasant brought with his aching heart to the far distant American garrison a fertile spore from some shady glen that he loved in Andalusia, or perhaps the seed ripened in a Devonshire lane and came thence with the besieging and conquering English, or yet again it may have been Florida born and carried thither on some soft wind of winter or in the blanket of an imprisoned Seminole. Centuries go by and bring a thousand accidents caught in the trailing garments of the years. I know only that the plant is there, wondrously beautiful by day, and that as the first hour of Christmas glided over the old fort the full light of the moon poured in at the barred window and built its exquisite texture into a mystic cradle veiled in the velvety purple darkness of the ancient cell.

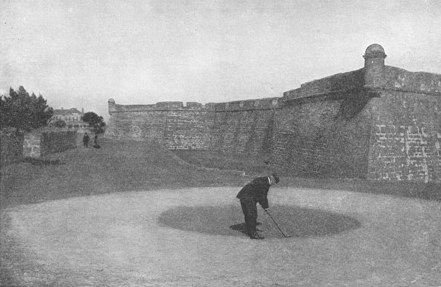

Without was the open court

flooded with the full radiance of the great Southern moon, the same

that looked down upon the miracle of birth in Bethlehem more than

nineteen hundred years ago. Within was the still darkness of the

manger-like place, and this cradle of a texture such as no human hands

might make, all strangely lighted and glorified by the beams from high

heaven. Not millions in money nor trained architects nor the most

skilled artisans of the day, all of which have been lavished upon the

building of the new St. Augustine, have produced one spot so mystically

beautiful as was at that hour the angle of that dark cell in the

casement of the fort that was once the whole of the old town, the fort

that waits in crumbling beauty, neglected but dignified still, the

obliterating hand of the coming centuries.  “The fort that waits in crumbling beauty the obliterating hand of the coming centuries.”

Dawn brought out of the

white stillness of the night a cloud from the southeast, and soon the

tepid air of the Gulf of Mexico was spilling rain upon all things and

hushing the barbaric greeting of guns and firecrackers with which the

Southern negro delights to hail Christmas morn. Then as April had

driven December from the sky, so came October with a westerly wind and

golden sunshine that merged in a night fall whose sky was of amber with

a green gold moon rounding up once more in it. Over in the west hung a

yellow, shining star of evening, and as the lights flashed out one by

one in the great hotels and their careful shrubbery glowed with fairy

lamps, it seemed as if this star shed upon them some of the kindly

light that led Balthazar and his companions of old, a star hanging in

the west, for a sign that the day, now grown old with us, was dawning

with new people in new lands. |