(Return to Web Text-ures)

Little Gardens

Content Page

Click Here to return to

the previous section

(HOME)

(Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to Little Gardens Content Page Click Here to return to the previous section |

(HOME) |

|

II

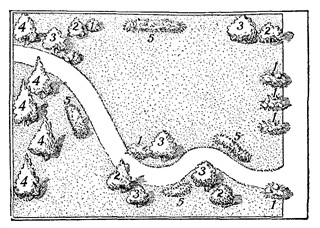

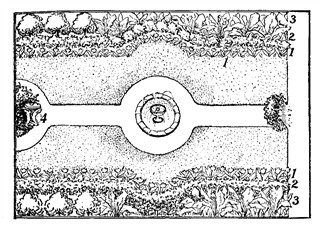

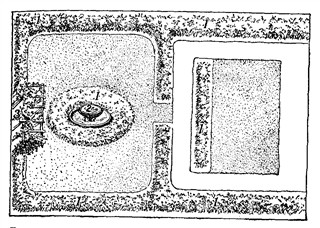

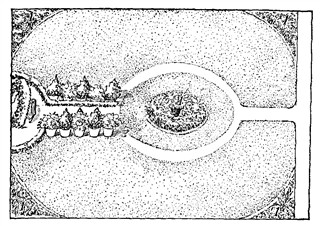

THE CITY YARD THAT your estate of twenty-five by sixty may be a place of beauty, in truth, you will determine on the form of it in the fall, so that it may come into bearing early, and so that there may be no disfigurements and eliminations through the correction of mistakes, after it is in flower. Let your lines and forms be simple and direct, and use color and foliage in masses, instead of in detached bits. Indeed, massing is necessary to simplicity. Put like with like, and aim for broad effects, rather than for diversity. Be formal rather than negligent, but do not carry formality to fantasy and grotesqueness. And here another problem offers: Shall we make a formal garden where all the surroundings are formal, or shall we seek to offset formality by lines of grace and freedom ? I grow more and more to believe that we must civilize our surroundings when we break away from nature so completely as we must in town, and that it is a parody on nature rather than a reminder of her beauties when we attempt to illustrate the phases of the great world in a back yard. A formal garden enables us to utilize our space most fully; it exposes the whole yard at a view; it gives opportunity for the cultivation of a sufficient variety and of brilliant groups. Harmony is better esthetics than contrast, wherefore the fixity of the garden plan conforms not disagreeably to the stubborn architecture that hems it in. If the yard is a large one, then, indeed, we may undertake to create some landscape and to soften the environment, but it is hard to make a substitute for fields, woods and hills in a place where Mary Ann has been drying the clothes. The Japanese, it is true, have the country in little in a quarter of an acre; but that resolves itself, after all, into another phase of formalism. They have miniature gardens, mountains, lakes, lawns and forests; for by pinching off the roots of maples and evergreens they confine those trees to a height of one or two feet. They induce a dwarf habit of growth. I once owned a couple of cedars that were fifteen or twenty years old, and were less than six inches in height. The Japanese landscape effects are on the same microscopic scale as these trees, and the seen-through-the-small-end-of-an-opera-glass gardens would not go well with four-story houses and the dust and ugliness of town. With the slight and pretty dwellings of the Japanese they are possible enough. If you are resolved on bringing nature into the town, it will signify that you are a man whose sympathies are not all for humanity, but have some reach into the world where gain and politics are not; while this, in turn, will mean that you desire to be yourself, rather than to be other men, taking color from nature, rather than society; hence, you will esteem privacy, at least, somewhiles, and will seek rather to escape the observation of the precinct than to be the focus of it. Therefore, your first care will be to close yourself about with vegetation. If it is permitted, you will plant trees at the end of your yard, train a hedge of privet along the sides of it, and mask your house, back and front, with ivy, ampelopsis, honeysuckle or wisteria. You will live in a jungle, barely penetrable by prying eyes and, I hope, as delightful, as it is secluded; and although you may reserve patches for flowers, the first aim will be to secure rich and concealing greenery. Now, the effect of space can be gained in narrow limits only by evasions and concealments. If your whole yard stands disclosed, if nothing is suggested or left to fancy, if there is no mystery, it must of need seem small, and its charm will be that of accuracy. Our informal yard will require trees or bushes tall enough to break the prospect, and to that end we must plant them in sinuosities, instead of right lines. Also, it will be well to place the smallest near the house, for it is another rule in gardening, so far as gardening can be confined by rules, to bring the smallest near, where the eye would otherwise overlook them, and let the tall, strong plants speak for themselves at a distance. Thus your wilderness will recede in ever-heightening masses, the remoter growths suggesting the edge of a wood into which one might penetrate for more than--well, six or eight feet. Here, then, is a scheme to gain this effect: The yard is given over to grass, chiefly, for, as there is much shade, flowers will not bloom copiously; and, again, if you insist on flower-beds in addition to so many shrubs and trees, the picture will be crowded and confused. There is not the least objection, however, to trellises enclosing the whole yard, and supporting sweet peas, trumpet-vine, passion-vine, honeysuckle, moon-flower, morning-glory or climbing roses. Such vines need not encroach on the yard itself, and if they are carried to a height of eight or ten feet they will add much to the seclusion, both actual and apparent. If flowers of smaller habit are used, wild ones will better consist with your plan than tame ones. I am fond of the wild things, and have grown them with success in a city yard, my golden-rod standing head high, with stems like willow branches for girth and stoutness; my buttercups unfolding in a very cloud--hundreds of shining blooms; my daisies starring the perspective with copious silver; and I know a front yard, two minutes from one of the busiest streets in New York, that, in the season, is beautiful with wild asters. In the plan, the objects numbered I are hydrangeas, rhododendrons or any other tough bushes that mark the beginning of the yard without too much exactness, and are not high enough to conceal those a little beyond. Those marked 2 are taller; weigelia, black currant, syringa, rudbeckia or any such, while number 3 are higher yet: privet, lilac and shadbush. The forms marked 4 are trees, preferably pines, hemlocks, firs or spruces, if your yard has fresh air and is near the outskirts; if not, don't doom these children of liberty to the crowd; choose, instead, some deciduous trees, or even erect a narrow arbor, or a trellis, to extend across the end of the yard, and clothe it heavily with vines. Number 5 stands for flower-beds. The arrangement in this manner of planting, which can be varied to any extent, has for its object the partial screening of the distance, so that the eye merely guesses at a beyond which isn't there, or is a different sort of beyond from one that you prefer to guess. The eye travels along a path that loses itself among syringas and lilacs, from whatever point near the house you may view it. The object of a path like that is rather to invite your eyes than your feet, for its windings suggest that it rambles on indefinitely. If your neighbor, dos a dos, falls in with this device, and will plant a few trees at the back of his yard, so that your forests adjoin one another, save for the fence (and if you are good friends that need no more stand in your way than if it were the constitution), your wild properties become almost impressive in extent. The objections to the plan are that it is much broken-cluttered, the housewife may say--and that grass will not grow well under trees, for it demands sun; but it has the advantage that it offers meditative walks, and a chair or bench or hammock placed under the trees, or in the arbor, permits you to enjoy a book, or the cool and fragrance of the evening, or the warmth and perfume of your cigar, in relative security against the hundred and fifty eyes at the back windows. Your forest will require frequent trimming, for unless you keep the vistas open and remorselessly check the attempts of the lilacs to fill the whole yard, you will presently have to fight for admission to your own premises. A more serious objection is that children, strangers, and Mary Ann, who is a law unto herself, will by no means travel on the path, for it is human nature, and especially American nature, and often a most excellent quality, to go straight to a designated object, considering grace and the neighbors not a whit; hence your path will be much neglected, and your grass much walked on. Even in parks, with police on duty as exemplars and enforcers of taste, people will take short cuts to save a bend.

Fig. 1: 1, 2, 3 Shrubs; 4, trees; 5, flower-beds.

Results in a Contracted Domain.

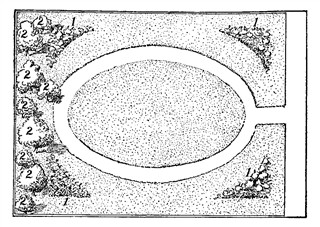

It is, therefore, with hesitancy that I suggest a still more radical but more conventional use of the curve. It is so completely artificial and against likelihood that I would hardly admit it here, were it not that I know people whose houses are only thirty feet back from the street, yet they must have a curved drive, in both directions, to the front door, and a porte-cochere for  Fig. 2: 1, Flower-beds; 2, trees and bushes.

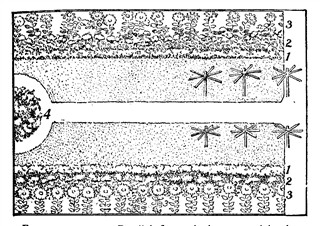

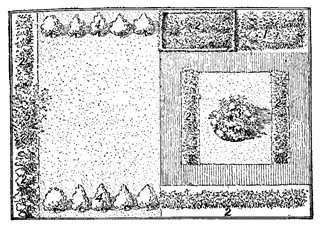

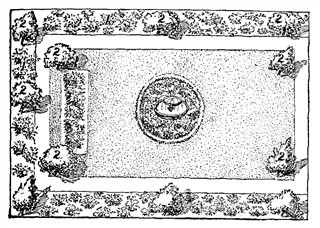

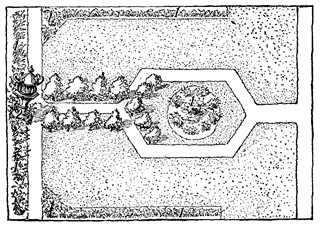

Mind, I don't say that this is pictorially bad, if I did make it myself, but only that it is un-American and impractical; that the young Indians in the family, seeing their bat or ball where they dropped it, at the farther end of the yard, would make a rush for it, and would wholly neglect the appointed means of arriving. Nobody would toddle around the oval but old persons, or guests whom you had invited to admire the effect, and who were looking for more important favors in the future. But if there are no Indians, and no Mary Ann, the oval lawn is rather pretty, don't you think? Unless you were to plant flowers in a smaller oval in the center, there is no place for flowers inside the walk, and you must have grass. It is the symbol and the proof of plenty. Our soft-breasted earth yields treasure to her children for the asking, yet never in such wise as when we cut the grass. For other crops are planted by men's hands; they have sown and watched and weeded; they have spent their strength in plowing, harrowing, watering, spraying before the harvest was to be gathered. But grass is the world's freest gift, and the freest is often the finest, like the night spectacle of the stars, and the splendors of the sunset. Grass grows in the tropics, and the arctics, too. In the warm darkness, where the seed has sunk, strange chemistries go on: the grain of weightless matter has thrown out its threads of white, to steady the blade it will presently send up and grip the earth. These blades, in multitude beyond the swords of all the armies, thrust aside the sand and stones and flourish, shining, in our sight. Wonder of life, that the woody atom, dropped into a morsel of soil, has been able to take to itself, not only the warmth of the sun and the wetness of the rain, but the very substance of the planet, and make inert mineral turn green and breathe! For herein is God; herein is mall to see his own continuance; here is the like of all greater creations, and the miracle in the spear of grass is not less than that of the revolving worlds. Have it near your eye; let it creep to your door; for this clothing of the globe is fair to all the senses. What wonder that the farmer, walking in his fields, shines his content at his eyes when all about him is this urging and increasing life. It falls in his service without the coming on of bitterness. Each hillock of drying grass utters fragrance, and is a lure, instead of a reproach. Every blade has had its day and has come to the end of it in fullness of life and exuberance of spirit. It is charged with myriads of glistening atoms of silica, which have given strength to it to stand erect and hold its flowers to the sun. It is yet strong with the firmness of the rock. And that strength shall pass into the fleetness of horses; sheep shall eat and clothe us with the warmth that the grass has borrowed from the summer; meek-eyed cattle with sweet breaths shall return it to their masters in food and drink. And the grass-blade has a power, that we have not, to feed upon the ground. We of dainty stomach need that others shall live first, and give their lives to us. It is, then, no less a moral law than a law of nature that we shall fulfill destiny by giving of ourselves for others, even like the grass. We stand firmest and highest when we stand alone, yet our service is for all, and according as we stand apart we have the more fertility to give. In this again we are as the grass. We are not as if each were an entity; we are only of the type; but as we increase, so shall the type prevail. Like the grass, we must convert the dark and hard to brightness. The lesson is something obvious, yet in heeding it we obey the law, not merely of a conscience, but necessity. Therefore, again, let there be at your doors a plenty of grass for your eye and your inner understanding to rest upon. It is a law in landscape-gardening that a path is to bend only to accommodate itself to the lay of the ground: to go around a knoll, or avoid a hollow, a pond, a ledge or a tree. You see that, in the first sketch, no such interruptions exist, so we had to make them by planting trees where the curves were desired. The continuous curve in the second conceit is wholly arbitrary; it is a softening of the more usual rectangular lay-out, and is designed to be viewed from the second-floor windows. The first device is less formal; still, if it mislikes you, (and I don't like it, altogether,) or if the folks next door protest that you have no right to plant trees that will throw a killing shade on their flower-beds and extend their roots under the fence, to the stealing of moisture--because folks who live next door to people are apt to do just this, being an inconsiderate company--you can subdue your yard to good uses, none the less, and be agreeable, in spite of being more customary than if you raised jungles. If they will not let you have trees, or if, as is more probable, you decide that you haven't room enough, your fence will stare you out of countenance, and a back fence must have been invented as a part of the punishment for leaving Eden. There is no more fearsome beast than your back fence. It is of close-fitted boards, six feet high, and painted white or drab. In New England they make a color that is used or found nowhere else, I believe; a blend of brown and lead that must have been inherited from the garb of the Puritans, hence, is as far from joy as colors can be; and this doleful hue, a stain of original sin, they delight to smear upon their fences. It may be the contemplation of this color, in the fences of Cambridge, that produces such frantic outbreaks of conduct in Harvard, for aught we know. But as you go southward you see less of this melancholy, and an attempt to simulate gaiety with buff or whitewash. If you find it possible to agree with the man next door, or if he consents to drown his offspring, you can tear down the structure; or, if a partition is really necessary, you can plant box, or privet, or even a row of lilacs; but, be sure of your man, for he may have saved an urchin child from the sacrifice, or he may own a large and vehement dog of the breed that delights to leap over obstructions and riot over forbidden premises. There will be a sad to-do, in such a case, over the uprooting of the hedge and the reversion to boards; but--whisper! You can let the hedge remain, and run a barbed wire or electrified netting along your side of it. If you have a fence, make it as innocuous as possible by coloring it a light and cheerful green, to conform to the vegetation. Do not paint it: stain it; and don't, for goodness' sake, make it a bilious green, but a yellow green. That shade of yellow which in the speech of the commoner is denoted as "yaller" suggests liver complaint; but yellow is a color to use without a green admixture, if your yard is a haunt of shadows, and needs inspiriting. Yellow is the sunniest, happiest color in the world, though we use the name as an adjective of contempt. You remember the yellow suite in Marie Antoinette's apartments at Versailles, and how the sun seems to shine there on the dullest days. With a yellow or yellow-green fence, and such sparks of golden light splashed against it, and over the sward, as Persian roses, marigolds, nasturtiums, coreopsis, zinnias, buttercups, rudbeckia, chrysanthemums and cannas, you will have a remedy against the blues. If you merely rent the place, and the landlord, being a man without a glimmering of taste or a prompting toward helpfulness, declines to stain the fence, leaving it covered with whitewash or shiny paint of an ugly or staring color, be not as one without hope. Drive pegs into the ground, fasten strings from them to nails in the top of the fence, plant morning-glory, and in a few weeks the dismal object will be hidden from sight, while you will be able to spend most of your spare time in pulling up little glories that will have seeded themselves all over the yard. The Calabrian invasion of America is alone to be compared with the enthusiasm of the morning-glory for expansion. If the people next door do not object--and why should they, since they share the show? you can erect a trellis clean around your yard for the more and better exhibition of the other climbing things and the increase of privacy. A substitute for a trellis is a strand or two of wire carried above the fence top for a foot or so by pickets; but be careful not to impose too heavy a burden upon the wire. A mass of vegetation, especially after a rain, or a showering with the hose, weighs twice as much as you tell yourself is possible. Having, then, composed your mind respecting the fence, and come to the conclusion that a conventional design for the yard is more suitable in a city than the first plan, let us see what can be done with our space. Suppose we try something formal--no Italian garden, bless you, but one that shapes itself withal to the size and form of our reservation, and better, on some accounts, for a front yard than a back one; only, if you have flowers in the front yard, you will have most of the children of the neighborhood there; hence, you must add ferocious bloodhounds and awful serpents to your menage. The scheme is simple: a central walk, ending at a semicircular bed (4), with a small tree, mound, rockery, bench, niche or conspicuous foliage plants; strips of lawn on either side of the way, and parallel beds beyond the lawns (I, 2 and 3 ), the first devoted to plants of low growth, the second to higher, and the third to the highest, with a trellis still behind and above them, if you like. The exhibits are thus arranged in steps, so that all are in view at once, and the show of bloom can be superb. In fact, if the yard is dished --that is, if it hollows a little in the center--it can be terraced, the platforms ascending in rises of six or eight inches; but that sort of thing is to be avoided, ordinarily, because terracing means retaining walls, and masonry means just so much room taken from the cultivable portion of your domain; then, if it is not upheld by a front of brick or stone, as well as a strengthening addition to the fence, your terrace will wash down in a heavy rain or thaw, and become unsightly; and, lastly, such things require to be done on a large scale, or they appear fussy and overdone. The uprights in the diagram stand for clothes-poles, if the domestic economies require them. It will be noted that they are placed on the lawns; hence it is not incumbent on Mary Ann to wade in among the heliotrope and mignonette--dainty little things, so suggestive of her own dainty self ! Or, revolving clothes-dryers, or poles with arms that project like spokes,, may be erected so near to the house that nothing but Mary Ann's desire to gambol will project her into the flower-beds. The advantages of the plan here submitted are simplicity and compactness. The yard is treated as a flower-bed and a lawn, rather than as a series of beds and lawns. There is no lost space. The lines follow those of the fences and party walls, and have not a particle of originality or character. Your flowers will have something of the appearance of exhibits on the shelves of a museum. Hard, set form will, therefore, be an attribute of this device. It can, however, be modified by the insertion of a central bed, the side beds being curved along their faces to conform to it geometrically. This breaks the severity of the plan somewhat, yet it is still rigid, and unless the neighbors had a good deal of green that appeared above their fences you would feel that you had more than your share of flowers, and they the less.  Fig. 3: 1, 2, 3, Parallel flower-beds; 4, semicircular flower-bed.

It would be better if the central circle were a pool or a fountain than a flower-bed, if circumstances permitted. That would relieve the appearance of crowding which would result from the addition of still another bed to those that occupy so large a part of the surface. If you would cultivate few varieties of flowers, but have a quantity of each, a division of this sort commends itself. If you filled bed number I with tulips, number 2 with hyacinths and kept number 3 for tall and hardy flowers, there would be a rare bravery of color and great delight of fragrance in the spring; then, after the fading, you could take out and store the bulbs for fall planting, and fill their places with summer bloomers. It is one of the temptations to a yard owner to work his ground to the limit, having so little of it; and while it insures constant bloom, to buy potted plants at the greenhouses, plunge them into the soil, keep them for a fortnight or so, then cast them out to make room for novelties, your real gardener will not do this. To say nothing of the cost, it is best to grow up with the plant children, to know their traits. You love them the better--pretty dependents--for ministering to their needs, and they reward the care with docile behavior and a cheery aspect. My own choice for a yard is for a preponderance of perennials, the good, hardy, reliable, free-bloomers of our grandmothers' gardens, that we can watch for in April and May with a certainty as absolute as the rising of Orion a few weeks earlier.  Fig. 4: 1, 2, 3, Flower-beds; 4, sun-dial.

The fixity of this arrangement in strips will make the yard seem longer, for when we break lines of that kind we seem to shorten them. We could soften the asperity of the plan in sundry ways, as by erecting an arch of wire at the entrance to the path, and training roses over it, or building an arch, midway, to span the yard itself and covering it with a vine. The result would be rococo; there would be a harking back to the Watteau and Boucher era, to the "hour, flower, bower" age of sentiment; and I am better in favor of as wide a space as the yard will give, enjoying the grass and reserving tall bushes and vines for places near to or against the fence. An arbor, if you must have one, should be of more substance than an arch of wire, and whatever large object we may elect to place as ornament in the yard--for our composition must have a central point of interest, a focus--is better at the end of the vista than the beginning of it, since we shall see it a hundred times from the door and windows to once that we will look toward the house. And as we shall see the yard oftenest from the windows, it is wise to have some equivalent matter to take the place that in a picture is occupied by the commanding figure, or the high light. Statuary needs space, and it needs to be good. But for this I should consent to a small and modest figure, half hidden by flowers and shaded by branches at the spot marked number 4 in the third plan, the trees behind the focal point in the first. White is all light, but it goes well with nearly anything. Still, we have to remember that marble figures are fragile and expensive, and a bronze nymph or satyr that had taken on the green of age, would best harmonize with its verdurous environment. Whatever you do, don't get one of those smirking, insipid statuettes of Flora, Ceres, Hebe or Ganymede that you find on the lawn of the parvenu--things that belong with the tatting tidy, the lamp in petticoats and the plush album. Nor must you buy a metal deer, elk, bear or lion to lord it over the premises and, assumably, to feed by night on the rhododendrons. We all know that such animals do not prowl about town yards. With the brassy freshness of the foundry yet upon them, they have as much relation to your posies as so many pounds of stoves. In fact, you are not pledged to use statuary. There are urns, sun-dials, jardinieres and fountains. You may attach a fountain spray to your hose and turn on the water in the evening, and the sparkling current, leaping from an ambush of cannas or marigolds will make a really pretty episode in the scene. In town the water will be low, just when you want to use it; then you may feel bashful about having your neighbors discover the fountain when they have trouble in getting enough to wash the dishes; so in that case, there remain the other adornments: a vase of bronze, for example, to be filled with pansies or nasturtiums, or a jardinière, preferably of Chinese or Japanese make, and of celadon, blue and white, or pale-green porcelain, in which may stand a rubber-plant or palm; or, a box with ornamental handles, or a painted tub. Avoid the tawdry French and German china; not that all the china from the modern potteries is tawdry, by any means, for the Orientals are now doing some deplorable work; but there is a refinement, delicacy, purity in the best Chinese porcelains that you will find in no other. Of course, the finest single colors in these fictiles are not for exposure to the breakage and the weathering of the garden. They are to be housed as preciously as Raphaels and Oriental rugs--works of art that the world may be doomed to see no more, now that commercialism has invaded the studios and the Orient, and cheap materials, hasty methods and insincere workmanship are rewarded as honesty and effort used to be. You need not use marble, bronze or porcelain for your central point of interest. Large and decorative plants will serve. The splendid green of the rubber-tree and the exquisite grace of palms, particularly the kentia, qualify these plants for decorative purposes. The kentia balmoreaha is an especially useful palm, less tender, more thrifty, larger and more beautiful in a northern climate than are some of the commoner species. A rockery is not a bad focus for a garden, either. These features may be combined by the exercise of a little taste and ingenuity, thus: a crescent of flowers in the bed number 4, third plan, a rock pile back of it, half concealed in vines or cacti, a jardiniere stoutly fixed in the front and center of the rockery, and a water spray arising from before the crescent. This group of objects, or any such, will pleasantly assert itself, and will both lend and borrow interest from its surroundings. The focus may be shifted to any part of the yard, and so long as the other contents are subordinate to it and not in rivalry, and so that the lines of composition tend toward it, it will remain a focus, and the eye will seek it. Or, for purposes of emphasis, a stout bush, a group of showy flowers, a tree, an old trunk covered with vine, a mass of morning-glory clambering up the pole of a bird-house: these will serve. Now, it

may be that the house is rented, and the owner

will not permit liberties to be taken with his real estate. You never

can

tell what manner of man an owner is going to be, when you sign a lease.

A

certain tenant whom I know had trained with care and affection a Boston

ivy

to cover a house front. It was a wondrous relief to a bleakly

unimportant

street. The vine broke into color early and kept of a polished and

healthful

green for six months. Along comes the landlord, looks at it, and

remarks,

"Well, when that stuff's all cut off, and a good coat of paint's put

over

them bricks, that'll be a good-lookin' house again." That is the sort

of

being who is likely to object to spading and planting, because they

might

interfere with the setting out of clothes-poles. A popular kind of

yard,

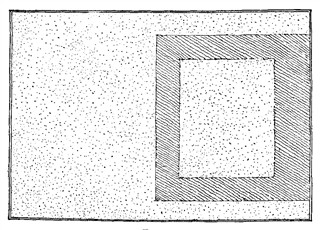

of his devising, is this:  Fig. 5

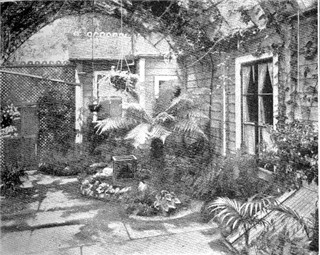

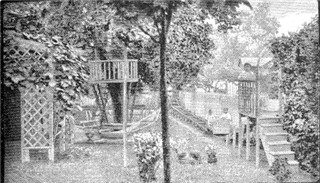

The shaded part expresses flagstones or asphalt; the rest is grass. I had the run of that pattern of yard for a season or two, and as it was the playground of sundry small boys of an inquiring turn respecting vegetation, which impelled them to take plants out of the earth now and then, to see how they were getting on, I did not undertake anything difficult. I adopted the simple scheme shown in Fig. 6. Grass

was the principal attraction here, yet, on a summer

evening after a good showering with the hose there was a deal of gaiety

in

the foreground and among the plebeian bushes that edged the fence. We

concealed

a part of that fence with glories, sweet peas, wild beans, and tried to

conceal

the rest of it with vines that made amazing pictures in the seedsmen's

catalogues, but that refused on any terms to enter into the picture made by our

premises--a circumstance that filled me with

grief and astonishment, for I had supposed that seedsmen's catalogues

were

as true as the Farmer's Almanac. ' We had one thing in that yard that

nobody

else had, willingly, and we were proud of it, namely, a

"jimson-weed"--the

stramonium, or thorn-apple, of the vacant lots. This had sown itself in

the

center of the back bed, and being picturesque of leaf and an oddity

among

cultivated plants, I spared it. Ordinarily, the sure way to kill a weed

is

to become attached to it, and give the same care to it that you would

to

an exotic. It will pine and die. "You never loved a dear gazelle--" and

all

that sort of thing, you know. But this Jamestown weed endured

prosperity

with a cheer that it was good to see. It grew and grew until it was the

prize

among its species. Out in California they have jimsons so big that you

can

play under them, but I speak now of our humble Eastern variety, which

is

usually of a dusty, weed-like aspect, rooted among ash-dumps, crockery

and

old cans, and lapsing into a squalor of age at the first nip of the

frost.

I hoed the soil about it, watered it, picked off the beetles and grubs,

and

when the flowers came, gathered them every evening, at least, all but

enough

to attract the night-moth, with its astonishing proboscis. The

determination

of that plant to have seed caused it to put forth blossoms in a

multitude,

and it swelled almost to the dimension of a tree. It was ten or a dozen

feet

wide and about nine feet high. It screened a ragged and unpleasant view

behind

us, and was really as handsome a property as many an owner of a private

park

could desire. There is a hint for any one who cares to act on it.  Fig. 6: 1, Wild garden; 2, Flower-beds; 3, rockery; 4, Shrubs and hardy plants; 5, jimson-weed.

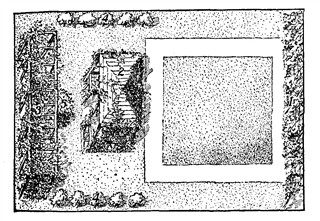

Adjoining our yard was its twin, but here is what the

owner did, and I instance this merely that you may avoid it:  Fig. 7: 1, Trellis reared against the house; 2, summer-house; 3, arbor; 4, plants; 5, flower-bed.

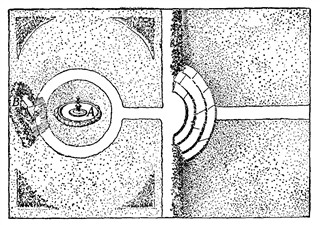

Here was architecting on an 18 × 50 with a vengeance. The summer-house and arbor were so heavily blanketed with vines that they were dark, damp and soon grew rickety, while the shadows they cast hindered or killed vegetation around, them, and the spaces between them and the fence were such wee, pinched areas that they could pot be farmed at a profit. The covering of this reservation with planks and lath exemplifies a common tendency of Americans to do too much of everything. They overeat, overdress, overgain, overlegislate, they cram too much into their houses, and up to a certain time of life try to cram too much into their heads. The Japanese have something to tell us in respect of art and life. They simplify them. The rich man in Japan does not show everything he owns. He puts out certain bronzes, vases, wall hangings, crystals, carvings and the like of that for a day or a week, then retires them to his chests and cabinets, and produces another set. He would as soon think of wearing all his clothes at once as of showing all his ivories, porcelains, netsukes, lacquers, kakemonos and embroideries. We, on the contrary, are so fond of show and luxury that we convert our houses into shops and museums, and the same propensity for overdoing is not infrequently seen in country estates with their over-frequent rustic shelters, pewter statuary, and masonry that means nothing except a job for the mason. It is also seen in yards. One yard in my town has a rockery which the owner has bestrewn with statuettes and china, that I verily think he found in the ash-dumps. He does not realize that a house is better suited for such things than is a place where green will grow. I have seen objects in a yard that were not artistic, yet that heightened the interest of locality, or hinted at resources of place or family history. In quartz countries, for instance, rockeries of snowy blocks and chunks of crystal connect the yard with the environing land, and in sundry whaling towns I think we would not spare the ancient figureheads, the flagpoles, the ribs and vertebrae of whales that decorate the yards, any more than the after-cabins of dead ships which have been hauled up into the street to serve as summer-houses, kitchens or homes for the humble. These things, which impart a fine, fishy flavor to shore settlements, are grotesque when transferred to inland yards, unless by a strange chance they conform to some scheme of building or decoration in the house that overlooks them. A house like that of the New York Yacht Club, for example, which is a fairly successful, and certainly interesting attempt to continue on land a suggestion of the architecture of the sea, would be entitled to a summer-house in the form of an after-cabin in its yard, if it had a yard; but can anything be more out of place than a boat, serving as jardinière or flower-bed, in a yard five miles from water? So, if we must have constructions and other matters in our ground that are but remotely germane to its normal uses, let us have a thought for their fitness. One of the new-rich families in New York has, in the middle of the drawing-room, a Russian sleigh, highly ornamented with panel paintings, and a palm stands on its seat. Palms are so usual to Russia; and especially in sleighs! Well, of all the--however, it is no worse than putting an old carriage body or boat or packing-box into the garden and filling it with flowers; hardly so bad, in fact, because hardly so obstructive, as putting two summer-houses on a strip fifty feet long. Assuming that we are bound by the usual conditions as to space and flagging, and have to deal with the kind of yard figured in the last sketch, we can strike out a little more boldly and accomplish this:  Fig. 8: 1, flower-beds; 2, vase or fountains; 3, a tree, palm, rustic bench, rustic shelter or statue.

The scheme is formal, but there are curves to offset the angles, and the vase and bench, the distant object higher and larger than the nearer, serve to relieve any possible monotony of form or color--though, really, that can hardly exist in such a little space. Observe that the nearer division of the yard, which is surrounded by walk, is left in grass, except at its farther end. That enables Mary Ann to put out the wash without committing Bulgarian atrocities among the pansies. A continuous bed surrounds the yard, save where it brings up against the house, and throws out two little wings whereby it almost encloses the second lawn also. A space is left between them so as to afford access to this lawn without stepping across the bed. If there is much travel to and fro, the path may be extended around the oval, and so to the end of the yard; but so little space is left for grass that it seems a pity to sacrifice any of it. Even if it is worn a trifle, it will freshen after a wetting, and grass that is slightly injured is better than a walk that is not used. At number 2 a tall plant or group of plants will serve instead of vase or fountain as an effective center, but remember, again, to make it subsidiary in height, mass or color to whatever object completes the vista and occupies the place of distinction in the last bed. A piece of strong-colored Chinese or Japanese porcelain--not garish, mind; only positive--or a Japanese temple lantern of dull bronze, if it does not wear too alien an aspect, and is half concealed by vines and flowers, will serve at number 3, if the yard is so narrow that a bench, a rustic arbor or any larger object would appear disproportionate to its setting. Perhaps

the yard has a continuous walk, instead of the

commoner one that cuts it asunder, and in that case the scheme can be

modified

in this way:  Fig. 9.

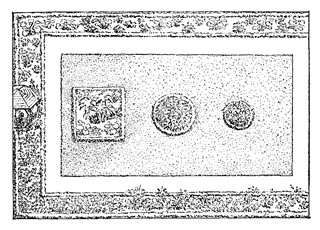

Here the beds surround the yard, as before, except on the house side, while in the lawn space are three other beds, progressively larger as they recede. The effect of this progression is to widen the yard, as the eye roves over it. This arrangement allows of the display of many varieties of flowers, though it is informally formal in its simplicity, and if trellises or wire net are added to the fence, as carriers for vines, and thus give more color and seclusion to your Horatian estates, the neighbors will probably call oftener than they did. Mary Ann, you see, still has the freedom of the first ten feet, and I must remind you that it is not necessary to plant clothes-poles for her. Nowadays it is usual to extend two beams across the yard, running from an upright on one fence to the other. The clothes-lines are strung from beam to beam, fastened to hooks, and a stout tug will haul the line so taut that poles will not be needed to support it. This is an advantage, for poles may fall and smash your ageratum or your salpiglossis --the same being no part of the human system. Mary Ann's fingers are usually buttered when she clutches any domestic materials that you especially wish she hadn't. A modification of this plan is shown in Fig. 10. As for

the walk, it ought to be narrow. Eighteen inches

is enough. You will doubtless make it of gravel, if you have the say

so,

and it certainly agrees best with the ground, so far as appearances go.

Stone

and brick, though ugly, have their advantages: weeds and grass do not

grow

on them, it costs no trouble to keep them clean, they are not kicked up and put

into disarray by heavy or shuffling

feet, and they are a check against weeds in the borders. It is not easy

to

repress the grass when it has no greater obstacle than gravel, which

will

be moistened in the showerings, but it stops when it touches asphalt or

flagstones. And if you would avoid trouble on this score, let your

garden-beds

come plumb to the edge of the walk, instead of leaving the usual strip

of

grass between them. The grass will never leave off trying to possess

itself

of the whole premises, and the fight against it, when it determines to

go

where it does not belong, will be unremitting. There is one variety, a

coarse

and riotous sort, known as witch-grass, that is downright uncanny in

its

sneaking and its strenuousness. You are transplanting a mignonette,

perhaps,

out of a crowded spot into a roomy one, and have thrust your trowel

four

or five inches into the earth, when you strike a long, white, ropy

root.

Get a firm grip, and lift it, by successive pulls, moving your hold

nearer

and nearer to its starting-place, until you reach its origin under a

bunch

of witch-grass and pluck the whole thing. You will find that the bunch

has

thrown out a star of these roots, some of them two feet long, which are

boring

and exploring in all directions, quite thankful to you for loosening

and

fertilizing the soll for them in the spring, and from each of these

runners

blades are starting toward the air. In turn these blades will become

deeply

anchored, and will send out root scouts to found new colonies. If

witch-grass

gets into your yard it is almost worth while to spade it up from end to

end,

chopping and overturning the sod to freeze and rot it through the

winter,

and making a fresh start with lawn-grass seed as soon as the snow is

off.

The war against weeds in the yard is, in object and effect, so like the

war

against the weeds and parasites in human society that one can readily

forbear

to publish any parables on the topic. Where a walk occurs between a

lawn

and a garden-bed, especially if it is a flagged walk, the grass roots

are

less apt to cross it than they are to underlap a space immediately

adjoining.

Thus, in one way, it means economy of labor to have as much walk as

possible,

and we have all seen "gardens" behind city houses that consisted

entirely

of flagstones, to Mary Ann's resounding joy, and the pained

astonishment

of moths, potato-bugs and persons who drifted into them. Let us pray

not

to have that sort of a garden ourselves, and to the end that we may

not,

we will continue our devising. Only, before leaving the subject of

grass,

let me caution you against making flower-beds in the form of stars or

anchors,

or human beings, because the slender points of soil exposed in the

outlining

of such extravagant devices are easily crossed by grass roots, and by

reason

of their narrowness are hard to reach with a hoe, except by disturbing

the

roots of flowers and plants of showy foliage that you may have set out

there.

If you have been so unwise as to make a star bed with long points in a

yard

containing witch-grass, you may as well decide to sit up all night with

it

and keep the grass out. If the people on either side of you, or behind

you,

have allowed this dreaded vegetable to establish itself on their

premises,

it will surely crawl under your fence, and the remedy is to spade

deeply,

vigorously and frequently all around that partition. It is one

advantage

of a brick wall, such as we seldom use in cities any more, that

forbidden

growths do not reach beneath it.  Fig. 10: 1, Flower-beds; 2, trees.

Supposing that you have the usual yard, but without walks,

so that you are at liberty to lay off your own, you can scheme one to

this

effect, which, as you observe, is merely a modification of Fig. 2; a

compromise,

if you like, in that it gives some direct path, and less of the oval.  A Garden and Something More.  On the Outer Edge of a City.  Fig. 11: 1, Flower-beds. By lengthening the walk at A, in the farther end of the yard, setting box borders on either side of it and placing bay-trees, spruces or tubbed saplings in rows outside the box, a pretty vista will be made that ought, of course, to end importantly, for an avenue of vegetation is a promise: you expect it to lead to something. Therefore, in pursuance of the formality thus expressed, it is fitting to end it with a statue, alcove, arbor, rustic chair or bench. Should a bench be put there, it may gain dignity and the occupants of it can secure shade if it is protected by wire fencing, the same to be covered with climbing roses or honeysuckle, the arch rising to a height of, say, nine feet. Still

following the formalities, we can go back to straight

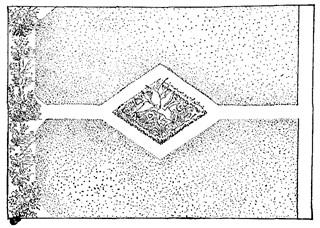

lines, and use them indirectly in a diamond pattern like this:  Fig. 12.

It

would be gorgeous, indeed, if you could cover the

whole of the diamond with flowers, planting canna in the middle, then

gladioli,

then dianthus, phlox, love-lies-bleeding, cockscomb and other flowers

of

red or ruddy hue till the progression ended at the walk in a border of

the

red alternanthera, or of ruddy coleus. The triangular corners marked B

could

be filled by tall and bushy plants--nothing better for this than stout

old

roses. The hindrances to the plan are Mary Ann's feet, for she has so

few

other places to plant them that flowers must serve; and again we have

been

a wee bit sparing of grass, unless the neighbors have a deal of it that

is

in view from our own premises. Also, the divergent walks seem indirect

for

direct and wakeful people. The floriculture could, therefore, be

restricted

to a circle in the middle of the diamond. A combination of the last two

plans

can also be expressed in this:  Fig. 13: 1, Flower-beds; 2, statue or lantern.

This, like some of the other gardens, must be laid off by permission of the kitchen powers, for if they decide for clothes, the clothes must have more space and their wearers will accustom themselves to self-denial and hard-boiled shirts. It will be noted that of the flower-beds thus far, or to be shown, all are of simple form. I am opposed to "carpets," at least in yards, and to pictures and mottoes, and to topiary and all extravagances of artifice. There may, possibly, be occasion for beds in the shape of harps, clocks, flags, houses and lions, but such occasions can not occur in the home garden whereof we treat. In brief, I am opposed to difficulty for its own sake. There may be virtue in the postulate of art for art's sake, and acrobatics for hardship's sake, and Maine laws for the land's sake, but it would be an easier, pleasanter world if we applied our strength to changing things for the better, instead of making things to change, then changing them to what they are now. Simple things are the comprehensible, the agreeable, the permanent, and the universe prefers them. Therefore, let us not be above them in our gardens. Because

of the smallness of space in a yard, it is better

not to have it cut up or divided by fences, but a change in level from

front

to rear may make it compulsory to terrace it, say, across the middle.

If

it is a sharp change, or if shifting sand makes it hard to bank it, the

rise

of the terrace can be vertical and faced with masonry--a thing commonly

to

be avoided in a small space. This retaining wall can be covered with

vines

or tall plants, save at the center, where a flight of two or three

steps

could give access to the higher ground. If the economies have to be

consulted,

those steps will doubtless be driven into the terrace, and will be no

wider

than necessary; but if the expense can be afforded it is better to have

them

extend from the terrace in widening crescents--marble against greenery.

Should

it be possible merely to slope the terrace and cover the slope with

turf,

instead of holding the upper section in place by stone, the flight of

steps

will be all the more graceful. Here is the plan.  Fig. 14.

This assumes that the back of the yard is higher than the house foundation. If the topography is the reverse of this, little change is called for, except to turn the steps the other way and to plant taller shrubs in the distant half of the yard, that they may be seen more readily from the lower windows. As a terrace pertains to formal gardens, we can use a little more strictness of form here than we might wish to apply to a level, and the upper portion, being pedestaled into a certain adventitious dignity, we can use a fountain at d, or a statue under an arch of roses at B, with less compunction than if they were just under the clothes-lines. It sometimes happens that the back of the yard abuts on a lower terrain, in which case you will be constantly losing real estate to your neighbor, after a shower. Or, it may be that you have an open fence there, or no fence, or that you are resolved on raising your own lettuce or strawberries. In that case a hedge is excusable, and might be laid off in this form:  Fig. 15: 1, Flower-beds; 2, the hedges; 3, the focal point or vista end.

This plan is easily modified; the middle bed can be made square, or diamond shaped, or what not. Its main points are the concealment of space behind the hedges, for vegetables, or, if there is nothing to conceal, it is still a good place for trees. If the ground just behind this area is lower, it is wise to plant tough shrubs along the edge of the declivity and plant them thickly, in order to knit the soil together, and prevent little landslides that will eat back into your yard and provide valleys and cations that you do not want. The curve of the hedges gradually straightens, merging them into a row of bushes on either side of the yard. In harmony with this, it is permissible to border the walk, all the way, with box, a charming accessory of the old-fashioned garden, when well used, for the idea of a border agrees with that of a hedge, and the box, in its compact growth, toughness of stem, and opulent green, is the privet in little. Furthermore, a trellis could be constructed at the back, as shield against an offending prospect and background for a bust, if you want to put one there-my pen came near to writing, "or have one." Horrible thought! Should this notion of hedging the end of the yard please you so well that you decide to take more room there, to the end that you might have a nook where you could take your sewing or your tea, or where you could read while little Jonas tumbled on the grass, the line of privet could be set forward, straightened, allowed to grow to its full height of twelve feet, the trellis could be carried around three sides of the enclosure, and raised to the same height, and if all that did not protect you from observation and sunshine, a strip of light awning could be extended over a part of the space, attaching its ends to the trellis. Here, in the evening, chairs and tables could be brought, Japanese lanterns could be hung and the family could gossip over the demi-tasse and cigar, while mingling with the fragrance of the Havana would come the odors of the related nicotiana, setting its pale lamps for the lure of moths in the twilight. Water brings light and life into the dullest landscape, and it has been used pleasantly in gardens, even of the city. I hesitate to commend it in the yard, however, because of the mosquitoes that breed in it. For it is amusing to listen to the talk of draining, burning and oiling the Jersey and Long Island meadows, knowing that the talkers continue to place fire-tanks on their roofs in town, where millions of culex and anopheles get themselves born, and descend into the streets to prey on the multitude. One usually has to be saving of water in a city. Our towns are growing so large that the supplying of necessities to them is becoming a serious problem. Hence, it is not possible to have reservoirs in a yard where the water shall flow constantly, and so surely as it stagnates, so surely will the mosquito lay her eggs upon it, wigglers will develop, and for the rest of the summer you will visit your garden only in gloves and veils, or under cover of a smudge that will destroy all the sweetness of the flowers. If you do live in one of those rare towns that have water enough, and clear water, and can afford to change it once or twice a day --for it won't do to kill the mosquito larvae by oiling it, on account of the odor and look of it afterward--it is best to place the pit or tank at the back of the yard. A cement reservoir ten feet across, three feet deep, with a curb raised a foot above the ground is ample, but half of a hogshead, sunk in the earth, will cost much less, though in each case you have to meditate upon the necessity of engaging a plumber. In this aquatic garden you may raise papyrus, lotus, water-hyacinth, and water-lily, and it has one advantage over the flower-bed in that you do not have to cut away the overhanging growths to afford light to it. On the contrary, if your yard were big enough for trees of a drooping habit, the very place for them would be near this pool, where their inverted image paints itself against the reflected pattern of the sky. If it is deemed safe to omit the curbing, all the better, and the installation of the tank makes the fountain easily possible, because it makes some equivalent imperative: that is, you must get water into the tank after you have built it. The flower-beds near the water will be refreshed by the spray, and both beds and pond will gain in charm from one another. If you have such a pond, the water-flowers can be grown there in heavy, porous boxes, sunk at the bottom and filled with loam and compost. And after the water clears it is well to introduce gold and silver fish, not for appearance' sake alone, but because they purify the pond, consuming worms and insects that may fall into it. If, for any reason, fish are undesirable, try, by all means, to persuade some dragon-flies, or devil's darning-needles, to inhabit near. These beautiful creatures, the terror of the ignorant, who believe that they will sting and even "sew up people's ears," are absolutely harmless, and they are voracious feeders on the mosquitoes, that will breed in your lake if it is allowed to stagnate. The dragon-flies eat mosquitoes, both in the larval and winged states.

Possibly you are so unfortunate as not merely to be short

of water, in which case an aquatic garden is hopeless, but of soil.

Your

yard may be of sand, or builders' rubbish, in which not even purslain

will

grow. Well, luckier men have had to contend with harder problems. The

mansions

on Nob Hill, in San Francisco, are builded on sand that is little more

fertile

than a plate, or stove-lid, yet by sodding, fertilizing and watering it

has

been surfaced and is as green as the parks of Eastern cities. This

takes

time and some money, and circumstances not unconnected with the latter

commodity

may oblige you to create your garden by degrees. In the first year you

may

have to consider most of it as walk? raking up the coarser materials

and

strewing gravel over the paths. Yet, you can doubtless buy three or

four

loads of good loam; you may even have it of some lot owner for the

asking,

if you will pay the cartage. In that case a sparing array of beds may

presage

a larger one-some such device as this:  Fig. 16.

Here is another device for a stony yard where the earth has to be imported. The focus, in this case, is at the side. You can

surround each of these little beds with box,

so that when you are able to throw on more soil the plan will remain

until

such time as the yard is covered, and you can undertake planting on a

larger

scale. A few prefer a frame of box for the floral picture under all

circumstances, and cultivate a close little hedge of

it, a foot or more high, about every

bed, even such as are devoted to vegetables. Borders are needed when

the

beds are surrounded by graveled walks, but not when they are merely

openings

in the grass. They belong to the formal garden, and spaces cut in the

lawn

are less formal in their aspect. The delicious old gardens at Mount

Vernon,

that have been growing more beautiful since George Washington

cultivated

them, illustrate the use of borders. The beds are so sunk in box that

they

suggest being packed in boxes. They heighten the pleasant primness of a

formal

garden, to be sure, and suggest the tea-cup times of cup and hood, as

they

are suggested in old family silver, four-posted beds and wax candles.

Where

formalism is admitted, I own to an enjoyment of hedges and borders that

are

clipped down to a definite height and show vertical sides. They go with

smooth-shaven lawns and flower-beds of geometric outline. But pray stop

there.

Don't distort your poor cedar, yew, privet, box or Osage orange into a

crowing

cock, a rampant bear, or an heraldic dragon. Don't deceive yourself

into

supposing that you commend the tree when you ask your friends to admire

it.

You are merely requesting praise for your own misplaced cleverness, and

one

of these days the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Trees may

hear

about you. There may be an occasion for trimming a tree into a cube, a

cylinder,

a column, a globe, an umbrella, or a cone, though I can't imagine it,

and

in these shapes we see, reduced to precision, some forms that trees

will

hint at on their own initiative; but a tree never willingly posed as a

likeness

of a giraffe, or a gentleman in a cocked hat, or a corkscrew, or a

decanter,

and it is an outrage on vegetable dignity to ask it.  Fig. 17.

In the square-topped hedge or row, the effect is different. We feel it with the eye as part in a plan of garden architecture, its firm, level lines are restful, it substitutes itself for a wall; hence, it takes its form, it thickens, moreover, with trimming, so as to serve all the better as partition. Topiary, or tree sculpture, is especially ridiculous in small spaces. It is not formalism: it is grotesquery. Have none of it. In sum, I would say that in the treatment of a city yard be moderately formal--that is, symmetrical-in a formal place; give to trees their natural form, lopping only straggling and obstructive growths; hide the fence with vegetation; group the flowers by sizes and colors; strive for broad, massive effects; avoid the finical and higgledy-piggledy; raise grass; use ornament with frugality and caution, but have a focus of interest, which need not be a geometric center. Click the Little Gardens Icon |