| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2018 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

| CHAPTER XI THE SOUTHERN JOURNEY Preparation: Depot A laid: First Days of the March from Winter Quarters: Start from Hut Point, November 3 When the

question of weight came to

be considered I could realise the seriousness of the loss of the four

ponies,

during the winter. It was evident that we would be unable to take with

us

towards the Pole as much food as I would have liked. I decided to

place a depot one

hundred geographical miles south of the Discovery

winter quarters, the depot to consist of pony wa:ze. The party,

consisting of

Adams, Marshall, Wild, Marston, Joyce and myself, left Cape Royds on

September

22 with a load of about 170 lb. per man, and the motor-car towed the

sledges as

far as Inaccessible Island, at the rate of about six miles an hour. We

took two

tents and two three-man sleeping-bags, for we expected to meet very low

temperatures. I had decided to take neither ponies nor dogs, so we took

the

sledges on ourselves, travelling over a fairly good surface as far as

the Discovery hut, where we passed

the first

night. The journey was a severe one, for the temperature, at times, got

down to

59° below zero Fahr. We reached the main depot in latitude 79° 36'

South,

longitude 168° East, on October 6. This we called " Depot A." It was

marked with an upturned sledge and a black flag on a bamboo rod. We

deposited a

gallon tin of oil and 167 lb. of pony maize so that our load would be

considerably reduced for the first portion of the journey when we

started

south. The weather was very severe on the return journey and we did not

reach

the old Discovery winter quarters

until October 13. We had been tewnty-one days out, but had been able to

march

only on fourteen and a half days. The next day we started for Cape

Royds and

had the good fortune to meet the motor-car a mile and a half south of

Cape

Barne. The sledges were soon hitched on, and we drove triumphantly to

winter

quarters — having travelled 320 statute miles since September 22. During our

absence the Northern

Party consisting of Professor David, Mawson, and Mackay, had started on

the

journey that was to result in the attainment of the South Magnetic

Pole. I had

said good-bye to Professor David and his two companions on September 22

and we

did not meet again until March 1, 1909. In chapter xxii. the Professor

tells

the story of the Northern journey. The Southern

Party was to leave

winter quarters on October 29; so on the return of the party from Depot

A we

commenced final preparations for the attempt to reach the South Pole. I

decided

that four men should go south, I myself to be one of them, and that we

should

take provisions for ninety-one days: this amount of food with the other

equipment would bring the load per pony up to the weight fixed as the

maximum

safe load. Early in 1907 I had proposed that one party should travel to

the

east across the Barrier surface towards King Edward VII Land but the

accidents

that had left us with only four ponies caused me to abandon this

project. The

ponies would have to go south, the motor-car would not travel on the

Barrier,

and the dogs were required for the southern depot journey. I deemed it

best to

confine the efforts of the sledging-parties to the two Poles,

Geographical and

Magnetic, and to send a third party into the western mountains with the

object

of studying geological conditions and, in particular, of searching for

fossils. The men

selected to go with me were

Adams, Marshall, and Wild. A supporting-party was to accompany us for a

certain

distance in order that we might start fairly fresh from a point beyond

the

rough ice off Minna Bluff, and we would take the four ponies and four

sledges. Arrangements

were made for sending

out a party early in December to lay a depot for the Northern Party.

When this

had been done, the same party would proceed to the western mountains.

On January

15, 1909, a depot party, under the command of Joyce, was to lay a depot

near

Minna Bluff containing sufficient stores for the return of the Southern

Party

from that point. This same party was to return to Hut Point, reload its

sledge

and march out to the depot a second time, there to await the arrival of

the

Southern Party until February 10, 1909. If the Southern Party had not

arrived

by that date Joyce and his companions were to go back to Hut Point and

thence

to the ship. Before my

departure from winter

quarters on the southern journey, I left instructions which provided

for the

conclusion of the work of the Expedition in its various branches, and

for the

relief of the men left in the Antarctic, in the event of the non-return

of the

Southern Party. I gave Murray command of the Expedition in my absence

and full

instructions. The trials of the motor-car in the neighbourhood of the

winter

quarters had proved that it could not travel over a soft snow surface,

and the

depot journey had shown me that the surface of the Barrier was covered

with

soft snow, much softer and heavier than it had been in 1902, at the

time of the Discovery expedition. In fact

I was

satisfied that, with the Barrier in its then condition, no wheeled

vehicle

could travel over it. The wheels would simply sink in until the body of

the car

rested on the snowy surface. We had made alterations in the wheels and

we had

reduced the weight of the car to an absolute minimum by the removal of

every

unnecessary part, but still it could do little on a soft surface, and

it would

certainly be quite useless with any weight behind, for the driving

wheels would

simply scoop holes for themselves. The use of sledge-runners under the

front

wheel, with broad, spiked driving-wheels, might have enabled us to get

the car

over some of the soft surfaces, but this equipment would not have been

satisfactory on hard, rough ice, and constant changes would occupy too

much

time. I had confidence in the ponies, and I thought it best not to

attempt to

take the car south from the winter quarters. The

provisioning of the Southern

Party was a matter that received long and anxious consideration.

Marshall went

very carefully into the question of the relative food-values of the

various

supplies, and we were able to derive much useful information from the

experience of previous expeditions. We decided on a daily ration of 34

oz. per

man; the total weight of food to be carried, on the basis of supplies

for

ninety-one days, would therefore be 773½ lb. The staple items were to

be biscuits

and pemmican. The biscuits, as I have stated, were of wheatmeal with 25

per

cent. of plasmon added, and analysis showed that they did not contain

more than

3 per cent. of water. The pemmican had been supplied by Beauvais, of

Copenhagen, and consisted of the finest beef, dried and powdered, with

60 per

cent. of beef-fat added. It contained only a small percentage of water.

The

effort of the polar explorer is to get his foods as free from water as

possible, for the moisture represents so much useless weight to be

carried.  THE MOTOR-CAR IN THE GARAGE, MAIZE-CRESHER ON THE RIGHT Pemmican 7.5 Emergency ration 1.5 Biscuit 16.0 Cheese or chocolate 2.0 Cocoa .7 Plasmon 1.0 Sugar 4.3 Quaker Oats 1.0 34.0 Everything was

ready for the start

on the journey towards the Pole as the end of October approached, and

we looked

forward with keen anticipation to the venture. The supporting-party was

to

consist of Joyce, Marston, Priestley, Armytage, and Brooklehurst, and

was to

accompany us for ten days. Day was to have been a member of this party,

but he

damaged his foot while tobogganing down a slope at the winter quarters,

and had

to stay behind. The weather was not very good during our last days at

the hut,

but there were signs that summer was approaching. The ponies were in

good

condition. We spent the last few days overhauling the sledges and

equipment,

and making sure that everything was sound and in its right place. In

the

evenings we wrote letters for those at home, to be delivered in the

event of

our not returning from the unknown regions into which we hoped to

penetrate. Events of the

southern journey were

recorded day by day in the diary I wrote during the long march. I read

this

diary when we had got back to civilisation, and arrived at the

conclusion that

to rewrite it would be to take away the special flavour which it

possesses. It

was written under conditions of much difficulty, and often of great

stress, and

these conditions I believe it reflects. I am therefore publishing the

diary

with only such minor amendments in the phraseology as are necessary in

order to

make it easily understood. The reader will understand that when one is

writing

in a sleeping-bag, with the temperature very low and food rather short,

a good

proportion of the "ofs," "ands" and "thes " get

left out. The story will probably seem bald, but it is at any rate a

faithful

record of what occurred. I will deal more fully with some aspects of

the

journey in a later chapter. The altitudes given in the diary were

calculated at

the time, and were not always accurate. The corrected altitudes are

given on

the map and in a table at the end of the book. The distances were

calculated by

means of a sledge-meter, checked by observations of the sun, and are

approximately accurate. October

29,

1908. A

glorious day

for our start; brilliant sunshine and a cloudless sky, a

fair wind from the north, in fact, everything that could conduce to an

auspicious beginning. We had breakfast at 7 A.M., and at 8.30 the

sledges that

the motor was to haul to Glacier Tongue were taken down by the penguin

rookery

and over to the rough ice. At 9.30 A.M. the supporting-party started

and was

soon out of sight, as the motor was running well. At 10 A.M. we four of

the

Southern Party followed. As we left the hut where we had spent so many

months

in comfort, we had a feeling of real regret that never again would we

all be

together there. It was dark inside, the acetylene was feeble in

comparison with

the sun outside, and it was small compared to an ordinary dwelling, yet

we were

sad at leaving it. Last night as we were sitting at dinner the evening

sun

entered through the ventilator and a circle of light shone on the

picture of

the Queen. Slowly it moved across and lit up the photograph of his

Majesty the

King. This seemed an omen of good luck, for only on that day and at

that

particular time could this have happened, and today we started to

strive to

plant the Queen's flag on the last spot of the world. At 10 A.M. we met

Murray

and Roberts, and said good-bye, then went on our way. Both of these,

who were

to be left, had done for me all that men could do in their own

particular line

of work to try and make our little expedition a success. A clasp of the

hands

means more than many words, and as we turned to acknowledge their cheer

and saw

them standing on the ice by the familiar cliffs, I felt that we must

try to do

well for the sake of every one concerned in the expedition. Hardly had we

been going for an hour

when Socks went dead lame. This was a bad shock, for Quan had for a

full week

been the same. We had thought that our troubles in this direction were

over.

Socks must have hurt himself on some of the sharp ice. We had to go on,

and I

trust that in a few days he will be all right. I shall not start from

our depot

at Hut Point until he is better or until I know actually what is going

to

happen. The lameness of a pony in our present situation is a serious

thing. If

we had eight, or even six, we could adjust matters more easily, but

when we are

working to the bare ounce it is very serious. At 1 P.M. we

halted and fed the

ponies. As we sat close to them on the sledge Grisi suddenly lashed

out, and

striking the sledge with his hoof, struck Adams just below the knee.

Three

inches higher and the blow would have shattered his knee-cap and ended

his

chance of going on. As it was the bone was almost exposed, and he was

in great

pain, but said little about it. We went on and at 2.30 P.M. arrived at

the

sledges which had gone on by motor yesterday, just as the car came

along after

having dragged the other sledges within a quarter of a mile of the

Tongue. I

took on one sledge, and Day started in rather soft snow with the other

sledges,

the car being helped by the supporting-party in the worst places.

Pressure

ridges and drift just off the Tongue prevented the car going further,

so I gave

the sledge Quan was dragging to Adams, who was leading Chinaman, and

went back

for the other. We said good-bye to Day, and he went back, with

Priestley and

Brocklehurst helping him, for his foot was still very weak. We got to the

south side of Glacier

Tongue at 4 P.M., and after a cup of tea started to grind up the maize

in the

depot. It was hard work, but we each took turns at the crusher, and by

8 P.M.

had ground sufficient maize for the journey. It is now 11 P.M., and a

high warm

sun is shining down, the day calm and clear. We had hoosh at 9 P.M.

Adams' leg

is very stiff and sore. The horses are fairly quiet, but Quan has begun

his old

tricks and is biting his tether. I must send for wire rope if this goes

on. At last we are

out on the long

trail, after four years' thought and work. I pray that we may be

successful,

for my heart has been so much in this. There are

numbers of seals lying

close to our camp. They are nearly all females, and will soon have

young.

Erebus is emitting three distinct columns of steam to-day, and the

fumaroles on

the old crater can be seen plainly. It is a mercy that Adams is better

to-night. I cannot imagine what he would have done if he had been

knocked out

for the southern journey, his interest in the expedition has been so

intense.

Temperature plus 2° Fahr., distance for the day, 14½ miles. October 30.

At Hut Point. Another gloriously fine day. We started away for Hut

Point at

10.30 A.M., leaving the supporting-party to finish grinding the maize.

The

ponies were in good fettle and went away well, Socks walking without a

sledge,

while Grisi had 500 lb., Quan 430 lb., and Chinaman 340 lb. Socks seems

better

to-day. It is a wonderful change to get up in the morning and put on

ski-boots

without any difficulty, and to handle cooking vessels without " burning

" one's fingers on the frozen metal. I was glad to see all the ponies

so

well, for there had been both wind and drift during the night. Quan

seems to

take a delight in biting his tether when any one is looking, for I put

my head

out of the tent occasionally during the night to see if they were all

right,

and directly I did so Quan started to bite his rope. At other times

they were

all quiet. We crossed one

crack that gave us a

little trouble, and at 1.30 P.M. reached Castle Rock, travelling at one

mile

and three-quarters per hour. There I changed my sledge, taking on

Marshall's

sledge with Quan, for Grisi was making hard work of it, the surface

being very

soft in places. Quan pulled 500 lb. just as easily and at 3 P.M. we

reached Hut

Point, tethered the ponies, and had tea. There was a slight north wind.

At 5

P.M. the supporting-party came up. We have decided to sleep in the hut,

but the

supporting-party are sleeping in the tent at the very spot where the Discovery wintered six years ago.

To-morrow I am going back to the Tongue for the rest of the fodder. The

supporting-party elected to sleep out because it is warmer, but we of

the

southern party will not have a solid roof over our heads for some

months to

come, so will make the most of it. We swept the débris

out. Wild killed a seal for fresh meat and washed the liver

at the seal hole, so to-morrow we will have a good feed. Half a tin of

jam is a

small thing for one man to eat when he has a sledging appetite, and we

are

doing our share, as when we start there will be no more of these

luxuries.

Adams' leg is better, but stiff. Our march was nine and a half miles

to-day. It

is now 10 P.M. October 31.

This day started with a dull snowy appearance, which soon developed

into a

snowstorm, but a mild one with little drift. I wanted to cross to

Glacier

Tongue with Quan, Grisi, and Chinaman. During the

morning we readjusted our

provision weights and unpacked the bags. In the afternoon it cleared,

and at

3.30 P.M. we got under way, Quan pulling our sleeping equipment. We

covered the

eight miles and a half to Glacier Tongue in three hours, and as I found

no

message from the hut, nor the gear I had asked to be sent down, I

concluded it

was blowing there also, and so decided to walk on after dinner. I

covered the

twelve miles in three hours, arriving at Cape Royds at 11.30, and had

covered

the twenty-three miles between Hut Point and Cape Royds in six hours,

marching

time. They were surprised to see me, and were glad to hear that Adams

and Socks

were better. I turned in at 2 A.M. for a few hours' sleep. It had been

blowing

hard with thick drift, so the motor had not been able to start for

Glacier

Tongue. On my way to Cape Royds I noticed several seals with young

ones,

evidently just born. Murray tells me that the temperature has been plus

22°

Fahr.  THE SOUTHERN PARTY MARCHING INTO THE WHITE UNKNOWN November 1.

Had breakfast at 6 A.M., and Murray came on the car with me, Day

driving. There

was a fresh easterly wind. We left Cape Royds at 8 A.M., and arrived

off

Inaccessible Island at twenty minutes past eight, having covered a

distance of

eight miles. The car was running very well. Then off Tent Island we

left the

car, and hauled the sledge, with the wire rope, &c., round to

our camp off

Glacier Tongue. Got under way at 10 A.M., and reached Hut Point at 2

P.M., the

ponies pulling 500 and 550 lb. each. Grisi bolted with his sledge, but

soon

stopped. The ponies pulled very well, with a bad light and a bad

surface. We

arranged the packing of the sledges in the afternoon, but we are held

up

because of Socks. His foot is seriously out of order, It is almost a

disaster,

for we want every pound of hauling power. This evening it is snowing

hard, with

no wind. Adams' leg is much better. Wild noticed a seal giving birth to

a pup.

The baby measured 3 ft. 10 in. in length, and weighed 50 lb. I turned

in early

to-night, for I had done thirty-nine miles in the last twenty-four

hours. November 2.

Dull and snowy during the early hours of to-day. When we awoke we found

that

Quan had bitten through his tether and played havoc with the maize and

other

fodder. Directly he saw me coming down the ice-foot, he started off,

dashing

from one sledge to another, tearing the bags to pieces and trampling

the food

out. It was ten minutes before we caught him. Luckily one sledge of

fodder was

untouched. Ho pranced round, kicked up his heels, and showed that it

was a deliberate

piece of destructiveness on his part, for he had eaten his fill. His

distended

appearance was obviously the result of many pounds of maize. In the

afternoon three of the ponies

hauled the sledges with their full weights across the junction of the

sea and

the Barrier ice, and in spite of the soft snow they pulled splendidly.

We are

now all ready for a start the first thing to-morrow. Socks seems much

better,

and not at all lame. The sun is now (9 P.M.) shining gloriously, and

the wind

has dropped, all auguring for a fine day to-morrow. The performance of

the

ponies was most satisfactory, and if they will only continue so for a

month, it

will mean a lot to us. Adams' leg is nearly all right.  NEW LAND. THE PARTY ASCENDED MOUNT HOPE AND SIGHTED THE GREAT GLACIER, UP WHICH THEY MARCHED THROUGH THE GAP. THE MAIN BODY OF THE GLACIER JOINS THE BARRIER FURTHER TO THE LEFT We picked up

the other sledges at

the Barrier junction, and Brocklehurst photographed us all, with our

sledge-flags flying and th Queen's Union Jack. At 10.50 we left the sea

ice,

and instead of finding the Barrier surface better, discovered that the

snow was

even softer than earlier in the day. The ponies pulled magnificently,

and the

supporting-party toiled on painfully in their wake. Every hour the pony

leaders

changed places with the sledge-haulers. At 1 P.M. the advance-party

with the

ponies pitched camp and tethered out the ponies, and soon lunch was

under way,

consisting of tea with plasmon, plasmon biscuits, and cheese. At 2.30

we struck

camp, the supporting-party with the man-sledge going on in advance,

while the

others with the ponies did the camp work. By 4 P.M. the surface had

improved in

places, so that the men did not break through the crust so often, but

it was

just as hard work as ever for the ponies. The weather kept beautifully

fine, with

a slight south-east wind. The weather sides of the ponies were quite

dry, but

their lee sides were frosted with congealed sweat. Whenever it came to

our turn

to pull, we perspired freely. As the supporting-party are not

travelling as

fast as the ponies, we have decided to take them on only for two more

days, and

then we of the Southern Party will carry the remainder of the pony feed

from

their sledge on our backs. So to-morrow morning we will depot nearly

100 lb. of

oil and provisions, which will lighten the load on the

supporting-party's

sledge a good deal. We camped at 6

P.M., and, after

feeding the ponies, had our dinner, consisting of pemmican, emergency

ration,

plasmon biscuits and plasmon cocoa, followed by a smoke, the most ideal

smoke a

man could wish for after a day's sledging. As there is now plenty of

biscuit to

spare, we gave the gallant little ponies a good feed of them after

dinner. They

are now comfortably standing in the sun, with the temperature plus 14°

Fahr.,

and occasionally pawing the snow. Grisi has dug a large hole already in

the

soft surface. We have been steering a south-east course all day,

keeping well

to the north of White Island to avoid the crevasses. Our distance for

the day

is 12 miles (statute) 300 yards. November 4.

Started at 8.30 this morning; fine weather, but bad light. Temperature

plus 9°

Fahr. We wore goggles, as already we are feeling the trying light. The

supporting-party started first, and with an improved surface during the

morning

they kept ahead of the ponies, who constantly broke through the crust.

As soon

as we passed the end of White Island, the surface became softer, and it

was

trying work for both men and ponies. However, we did 9 miles 500 yards

(statute) up to 1 P.M., the supporting-party going the whole time

without being

relieved. Their weights

had been reduced by

nearly 100 lb., as we depoted that amount of oil and provision last

night. In

the afternoon the surface was still softer, and when we came to camp at

6 P.M.

the ponies were plainly tired. The march for the day was 16 miles, 500

yards

(statute), over fourteen miles geographical, with a bad surface, so we

have

every reason to be pleased with the ponies. The supporting-party pulled

hard.

The cloud rolled away from Erebus this evening, and it is now warm,

clear, and

bright to the north, but dark to the south. I am steering about

east-south-east

to avoid the crevasses off White Island, but to-morrow we go

south-east. We

fixed our position to-night from bearings, and find that we are

thirty-four

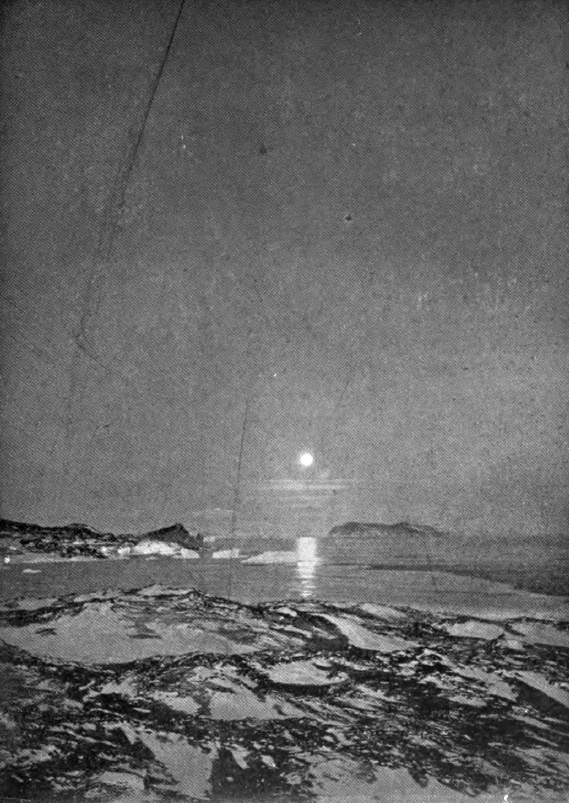

miles south of Cape Royds. Every one is fit and well.  CAPE BARNE AND INACCESSIBLE ISLAND BY MOONLIGHT November 6.

Lying in our sleeping-bags all day except when out feeding the ponies,

for it

has been blowing a blizzard, with thick drift, from south by west. It

is very

trying to be held up like this, for each day means the consumption of

40 lb. of

pony feed alone. We only had a couple of biscuits each for lunch, for I

can see

that we must retrench at every set-back if we are going to have enough

food to

carry us through. We started with ninety-one days' food, but with

careful

management we can make it spin out to 110 days. If we have not done the

job in

that time it is God's will. Some of the supporting-party did not turn

out for

any meal during the last twenty-four hours. Quan and Chinaman have

taken their

feeds constantly, but Socks and Grisi not so well. They all like Maujee

ration

and eat that up before touching the maize. They have been very quiet,

standing

tails to the blizzard, which has been so thick that at times we could

not see

them from the peep-holes of our tents. There are great drifts all round

the

tents, and some of the sledges are buried. This evening about 5.30 the

weather

cleared a bit and the wind dropped. When getting out the feed-boxes at

6 P.M. I

could see White Island and the Bluff, so I hope that to-morrow will be

fine.

The barometer has been steady all day at 28.60 in., with the

temperature up to

18° Fahr., so it is quite warm, and in our one-man sleeping-bags each

of us has

a little home, where he can read and write and look at the penates and

lares

brought with him. I read Much Ado About Nothing during the morning. The

surface

of the Barrier is better, for the wind has blown away a great deal of

the soft

snow, and we will, I trust, be able to see any crevasses before we are

on to

them. This is our fourth day out from Hut Point, and we are only twenty

miles

south. We must do better than this if we are to make much use of the

ponies. I

would not mind the blizzard so much if we had only to consider

ourselves, for

we can save on the food, whereas the ponies must be fed full. November 7.

Another disappointing day. We got up at 5 A.M. to breakfast, so as to

be in

time to start at 8 A.M. We cleared all the drift off our sledges, and,

unstowing them, examined the runners, finding them to be in splendid

condition.

This work, with the assistance of the supporting-party, took us till

8.30 A.M.

Shortly afterwards we got under way, saying good-bye to the

supporting-party,

who are to return to-day. As we drew away, the ponies pulling hard, our

comrades gave us three cheers. The weather was thick and overcast, with

no

wind. Part of White Island could be seen, and Observation Hill, astern,

but

before us lay a dead white wall, with nothing, even in the shape of a

cloud, to

guide our steering. Almost immediately after we left we crossed a

crevasse, and

before we had gone half a mile we found ourselves in a maze of them,

only

detecting their presence by the ponies breaking through the crust and

saving

themselves, or the man leading a pony putting his foot through. The

first one

Marshall crossed with Grisi was 6 ft. wide, and when I looked down

there was

nothing to be seen but a black yawning void, Just after this, I halted

Quan on

the side of one, as I thought in the uncertain light, but I found that

we were

standing on the crust in the centre, so I very gingerly unharnessed him

from

the sledge and got him across. Then the sledge, with our three months'

provisions, was pulled out of danger. Following this, Adams crossed

another

crevasse, and Chinaman got his forefoot into the hole at the side. I,

following

with Quan, also got into difficulties, and so I decided that it was too

risky

to proceed, and we camped between two large crevasses. We picketed the

ponies

out and pitched one tent, to wait till the light became better, for we

were

courting disaster by proceeding in that weather. Thus ended our day's

march of

under a mile, for about 1 P.M. it commenced to snow, and the wind

sprang up

from the south-west with drift. We pitched our second tent and had

lunch,

consisting of a pot of tea, some chocolate and two biscuits each. The

temperature was plus 12° Fahr. at noon. It blew a

little in the afternoon,

and I hope to find it clear away this pall of dead white stratus that

stops us.

The ponies were in splendid trim for pulling this morning, but, alas 1

we had

to stop. Grisi and Socks did not eat up their food well at lunch or

dinner. The

temperature this evening is plus 9° Fahr., and the ponies feel chilly.

Truly

this work is one demanding the greatest exercise of patience, for it is

more

than trying to have to sit here and watch the time going by, knowing

that each

day lessens our stock of food. The supporting-party got under way about

9.30 A.M.,

and we could see them dwindling to a speck in the north. They will, no

doubt,

be at Hut Point in a couple of days. We are now at last quite on our

own

resources, and as regards comfort in the tents are very well off, for

with only

two men in each tent, there is ample room. Adams is sharing one with

me, whilst

Marshall and Wild have the other. Wild is cook this week, so they keep

the

cooker and the primus lamp in their tent, and we go across to meals,

after

first feeding the ponies. Next week Adams will be cook, so the cooking

will be done

in the tent I am in. We will also shift about so that we will take

turns with

each other as tent-mates. On the days on which we are held up by

weather we

read, and I can only trust that these days may not be many. I am just

finishing

reading The Taming ol the Shrew. I have Shakespeare's Comedies,

Marshall has

Borrow's "The Bible in Spain," Adams has Arthur Young's " ravels

in France," and Wild has "Sketches by Boz." When we have

finished we will change round. Our allowance of tobacco is very

limited, and on

days like these it disappears rapidly, for our anxious minds are

relieved

somewhat by a smoke. In order to economise my cigarettes, which are my

luxury,

I whittled out a holder from a bit of bamboo to-day, and so get a

longer smoke,

and also avoid the paper sticking to my lips, which have begun to crack

already

from the hot metal pot and the cold air. NOTE. The

difficulties of travelling

over snow and ice in a bad light are very great. When the light is

diffused by

clouds or mist, it casts no shadows on the dead white surface, which

consequently appears to the eye to be uniformly level. Often as we

marched, the

sledges would be brought up all standing by a sastrugus, or snow mound,

canted

by the wind, and we would be lucky if we were not tripped up ourselves.

Small

depressions would escape the eye altogether, and when we thought that

we were

marching along on a level surface, we would suddenly step down two or

three

feet. The strain on the eyes under these conditions is very great, and

it is

when the sun is covered and the weather is thickish that snow blindness

is

produced. Snow blindness, with which we all became acquainted during

the

southern journey, is a very painful complaint. The first sign of the

approach

of the trouble is running at the nose; then the sufferer begins to see

double,

and his vision gradually becomes blurred. The more painful symptoms

appear very

soon. The blood-vessels of the eyes swell, making one feel as though

sand had

got in under the lids, and then the eyes begin to water freely and

gradually

close up. The best method of relief is to drop some cocaine into the

eye, and

then apply a powerful astringent, such as sulphate of zinc, in order to

reduce

the distended blood-vessels. The only way to guard against an attack is

to wear

goggles the whole time, so that the eyes may not be exposed to the

strain

caused by the reflection of the light from all quarters. These goggles

are made

so that the violet rays are cut off, these rays being the most

dangerous, but

in warm weather, when one is perspiring on account of exertion with the

sledges, the glasses fog, and it becomes necessary to take them off

frequently

in order to wipe them. The goggles we used combined red and green

glasses, and

so gave a yellow tint to everything and greatly subdued the light. When

we

removed them, the glare from the surrounding whiteness was intense, and

the

only relief was to get inside one of the tents, which were made of

green

material, very restful to the eyes. We noticed that during the spring

journey,

when the temperature was very low and the sun was glaring on us, we did

not

suffer from snow blindness. The glare of the light reflected from the

snow on

bright days places a very severe strain on the eyes, for the rays of

the sun

are flashed back from millions of crystals. The worst days, as far as

snow

blindness was concerned, were when the sun was obscured, so that the

light came

equally from every direction, and the temperature was comparatively

high. November 8.

Drawn blank again In our bags all day, while outside the snow is

drifting hard

and blowing freshly at times. The temperature was plus 8° Fahr. at

noon. The

wind has not been really strong; if it had been I believe that this

weather

would have been over sooner. It is a sore trial to one's hopes and

patience to

lie and watch the drift on the tent-side, and to know that our valuable

pony

food is going, and this without benefiting the animals themselves.

Indeed,

Socks and Grisi have not been eating well, and the hard maize does not

agree

with them. At lunch we had only a couple of biscuits and some

chocolate, and

used our oil to boil some Maujee ration for the horses, so that they

had a hot

hoosh. They all ate it readily, which is a comfort. This standing for

four days

in drift with 24° of frost is not good for them, and we are anxiously

looking

for finer weather. To-night it is clearer, and we could see the horizon

and

some of the crevasses. We seem to be in a regular nest of them. The

occupants

of the other tent have discovered that it is pitched on the edge of a

previously unseen one. We had a hot hoosh to-night, consisting of

pemmican,

with emergency ration and the cocoa. This warmed us up, for to lie from

breakfast time at 6 A.M. for twelve or thirteen hours without hot food

in this

temperature is chilly work. If only we could get under way and put some

good

marches in, we would feel more happy. It is 750 miles as the crow flies

from

our winter quarters to the Pole, and we have done only fifty-one miles

as yet.

But still the worst will turn to the best, I doubt not. That a polar

explorer

needs a large stock of patience in his equipment there is no denying.

The sun

is showing thin and pale through the drift. this evening, and the wind

is more

gusty, so we may have it really fine to-morrow. I read some of

Shakespeare's

comedies to-day. November 9.

A different story to-day. When we woke up at 4.30 A.M. it was fine,

calm, and

clear, such a change from the last four days. We got breakfast at 5

A.M., and

then dug the sledges out of the drift. After this we four walked out to

find a.

track amongst the crevasses, but unfortunately they could only be

detected by

probing with our ice-axes, and these disclosed all sorts, from narrow

cracks to

great ugly chasms with no bottom visible. A lump of snow thrown down

one would

make no noise, so the bottom must have been very far below. The general

direction was south-east and north-west, but some curved round to the

south and

some to the east. There was nothing for it but to trust to Providence,

for we

had to cross them somewhere. At 8.30 A.M. we got under way, the ponies

not

pulling very well, for they have lost condition in the blizzard and

were stiff.

We got over the first few crevasses without difficulty, then all of a

sudden

Chinaman went down a crack which ran parallel to our course. Adams

tried to

pull him out and he struggled gamely, and when Wild and I, who were

next, left

our sledges and hauled along Chinaman's sledge, it gave him more scope,

and he

managed to get on to the firm ice, only just in time, for three feet

more and

it would have been all up with the southern journey. The three-foot

crack

opened out into a great fathomless chasm, and down that would have gone

the

horse, all our cooking gear and biscuits and half the oil, and probably

Adams

as well. But when things seem the worst they turn to the best, for that

was the

last crevasse we encountered, and with a gradually improving surface,

though

very soft at times, we made fair headway. We camped for lunch at 12.40

P.M.,

and the ponies ate fairly well. Quan is pulling 660 lb., and had over

700 lb.

till lunch; Grisi has 590 lb., Chinaman 570 lb., and Socks 600 lb. In

the

afternoon the surface further improved, and at 6 P.M. we camped, having

done 14

miles 600 yards, statute. The Bluff is showing clear, and also Castle

Rock

miraged up astern of us. White Island is also clear, but a stratus

cloud

overhangs Erebus, Terror, and Discovery.

At 6.20 P.M. we suddenly heard a deep rumble, lasting about five

seconds, that

made the air and the ice vibrate. It seemed to come from the eastward,

and

resembled the sound and hakl the effect of heavy guns firing. We

conjecture

that it was due to some large mass of the Barrier breaking away, and

the

distance must be at least fifty miles from where we are. It was

startling, to

say the least of it. To-night we boiled some Maujee ration for the

ponies, and

they took this feed well. It has a delicious smell, and we ourselves

would have

enjoyed it. Quan is now engaged in the pleasing occupation of gnawing

his tether

rope. I tethered him up by the hind leg to prevent him attacking this

particular thong, but he has found out that by lifting his hind-leg he

can

reach the rope, so I must get out and put a nose-bag on him. The

temperature is

now plus 5° Fahr„ but it feels much warmer, for there is a dead calm

and the

sun is shining.  A QUIET EVENING ON THE BARRIER. |