| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2009 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

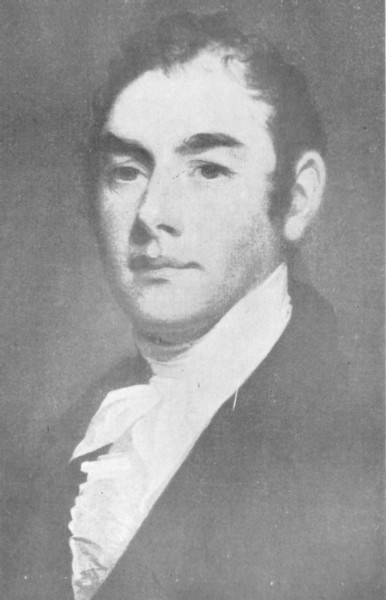

Governor King

By IONE B. FALES FOREWORD. William King was born in Scarboro in 1768, and his family was one of the most illustrious of his state. His grandfather, Richard King, came from England and settled in Massachusetts in the 18th century. William was one of the younger members of the family and the least favored in educational advantages, as his father died when he was but a lad. Entering the saw mill business in Topsham at the age of 21 years, he soon advanced to ownership of the business, and had extended his interests to extensive ship building and ventures. At the age of 27, he had already made a name for himself in politics, both locally and in national issues. In the War of 1812, he took an active part in the defense of Maine against the English and won military honors for himself. For years he was a Maine representative in the Massachusetts legislature and it was due largely to his efforts that Maine was finally separated from the mother state, in 1820. The people honored him with the position of Maine's first governor and he filled the place for a year with honor and dignity. In 1821, he was called by President Munroe to make one of a commission to settle the United States claims in Florida and left Maine for a time to take a place in national affairs. He died at his home in Bath on July 17, 1852, at the age of 85. In that city, Maine has erected over his resting place, an imposing granite shaft to mark his tomb. *

* *

THE ERRATIC cawing of a thieving crow, whirring in low flight above the cultivated fields of Scarboro, over a century ago, in quest of the tender tips of some luckless farmer's sprouting corn, snapped the impassive quiet of a country noon-day. To the stalwart country lad, halted at the fork of the Portland and Portsmouth pike, the harsh note of the raven seemed a voice of good omen. He lifted his eyes from idle contemplation of the separating highways before him to follow the course of the bird in its flight. Beside the boy, grazing half-heartedly by the edge of the road, two coal black steers were standing, in no more haste than their master to be on their way. Young William King, just turned 21, even in the crude homespun of his mother's weaving, bore his tall figure with a dignity that neither youth nor clothes could alter. He had been standing at the cross-roads for some moments before the crow's call had solved his problem for him. Before him, to right and to left, the two highways gave their invitation. On the one hand the road lay cool and serene, a damp brown ribbon of turf leading through tall aisles of forest trees. On the other hand, the vista was of equal worth. The pike, hot and dusty, reached out through cultivated fields and flowering meadows with the low roofs of farm houses visible at uneven distances along its path. Cattle were feeding here and the newly planted crops of corn and potatoes were growing toward a harvest. These evidences of practical industry offered themselves in mute contrast to the undisturbed serenity of the forest lane. "Caw! Caw! Caw!" The rude hunger song of the crow burst loud upon the air, then grew fainter and fainter, as the bird faded to a small black speck and was finally lost in the distances of the Portland pike. "I'll follow the crow," thought William King. So calling to his steers and driving them before him, he continued down the highway past the cultivated lands, where the crow had pointed out the way. Young King had that morning left his mother's home at Dunstan's Landing, a little settlement of the town of Scarboro and had started off with his steers, his sole heritage from his father's estate, to make his way in the world. In due time, he arrived in Portland and attempted to dispose of his cattle there. But Portland at the early date of 1789, was scarcely larger than Scarboro and offered no great advantages to an ambitious young man. No one, which was of greatest moment to him at that time, seemed desirous of a bargain in steers. Failing of a market, the young man continued his journey, this time turning his course to Bath, passing from there to Brunswick and thence to Topsham where he settled. Somewhere on the road, he had disposed of his steers and with this small capital in his pockets, William entered the saw-mill business in that village. On so small a happening as a raven's flight, that summer day, was a page in the later history of Maine determined and one of her greatest sons preserved to her whose steps chance might otherwise have turned to the sister state of New Hampshire. Such is the earliest glimpse that Maine history or legend, call it as you will, gives of her first governor, his Excellency, General William King. *

* *

Of William King, the governor, the soldier, the statesman and the captain of industry, the social leader and the polished gentleman, history is replete. Facts of his wonderful sway over the fortunes of Maine and his inestimable services in making Maine a separate state from Massachusetts, can be had in any volume of the history of his times.

But the personal touches which should give him the niche he deĽ serves in the hearts of the later generations of his native state, have escaped the pages of history and are learned only by sympathetic gleanings among the stories handed down by friends and intimates of the splendid governor's own day. Sidelights upon his personality, gained now from the reminiscence of an old servitor, but lately dead, now from personal letters to a friend, and again from tales handed down to their children by some of the first families of early Maine, give intimate, human details of the life of the great man. History pictures him as a stern, just man, of wonderful ability in trade and politics, successful in both affairs of state and affairs of his home. It gives him a dignity and graciousness, eminently fitting to Maine's first governor. But it leaves the reader overwhelmed with his coldness and aloofness to humdrum every day problems. To unwritten history is left the duty of infusing into this historical picture, the warmth of the personal touch. During the lifetime of the father, Richard King, young William had served his appenticeship in the saw mill trade under a rabid old Saco lumberman, and his harsh but thorough training now served him in good stead. It was but natural that the boy with scant resources at his command, should turn to the one trade he did know and gladly step into the opening a vacancy in the Topsham mill afforded. King went to work with a will, but genius was not to be smothered under a mechanical occupation and he had scarce become known in Topsham before he was rapidly striding to the front in business and politics. In partnership with William Porter, a brother-in-law, who also came to Topsham, he soon became owner of the mill business and immediately began to push his trade to the building of ships. Financial success was gained immediately and it was but six years after he had come to town that, at the age of 27, he began to be a state figure in politics. William King, early in his political career, was sent to represent Topsham at the King, Legislature. In company with the Hon. Peleg he set out for Boston. The old story has it that King and Tallman were the only men in Maine at that date whose boots were good enough to wear to the capitol. At any rate, while there, the wise young politician got possession of the immense tracts of land where the town of Kingfield is now situated. The town gained its name from its former proprietor, Maine's first governor. Countless acres of land in the Dead River district were granted to King and Tallman by the legislature with the understanding that unless the territory was settled within a certain date, the tract was forfeit. As the years passed and the terms of the grant were not fulfilled, the matter again came up before the Boston session. King was always strong at arguing and Tallman left it to him somehow to circumvent the letter of the law and keep possession of the land. So, in a witty and able speech before the legislature, with Tallman on hand to second his efforts, King convinced the Boston law makers that the Kingfield district was rightfully his and that upon payment of a certain sum by him and Peleg Tallman their claim should be confirmed for all time. His eloquence and personal magnetism prevailed. Tallman started post haste for Bath to secure the needed money. King stayed calmly at Boston, signed a note and had paid for the land before Tallman could return. This irregular method of closing the deal, turned a friend into an enemy and nearly brought on a duel. King refused to fight, however, saying it ill befitted the makers of the law to break it. Tallman was more fortunate than appearances first indicated. He died possessed of $600,000, while Governor King, though rich in land, was practically penniless at his death. King built for himself a huge homestead in the village which bears his name and in an annual journey to the Dead River region, encouraged his settlers to clear the land and erect dwellings. The old King place is still standing and is the chief historical landmark of the town which celebrated its one-hundredth anniversary in August, 1916. On a Sabbath morning in one of the last years of the eighteenth century, the first families of Bath were calmly making their way to the Old North church. The ladies in the elaborate costumes of the period, with flaring silks and quaint beribboned bonnets, seemed to be occupied with other matters than the orthodox Sunday thoughts. They were talking excitedly with each other and with the men of the congregation in half-suppressed whispers of expectancy, while to right and left, strict watch was kept as though to herald the approach of some looked-for stranger. "She was the belle of the season in Boston society, last winter," murmured a stately dame to a companion as they paused at the entrance of the church. "Indeed, she is the biggest beauty of the year," commented a serious-faced gentleman to a group of his fellows. "And as charming as she is beautiful," added another. "And as wise as she is charming," remarked a dignified citizen in military coat who had just entered the church yard. "Her gown should be of the latest Boston style," hopefully suggested a fashionably attired girl whose thoughts seemed strangely strayed to worldly subjects. The church bell tolled its final summons and the curious throng passed within doors and settled themselves in the sombre-cushioned pews for the morning worship. William King was that day to bring his bride to Bath and, as was the custom of the times, her first appearance was to be at the services on that Sabbath morning at the Old North church. King was one of the most distinguished and most sought after young men of his day in the aristocratic community of Bath, while his bride rumor had hailed as one of the beauties of the decade. The young statesman had been to Boston on state business, it was told, when the charms of Mistress Anne Frazier had quite captivated him. He had pressed his suit with ardor and had sent fine messages home to Bath of his bride's surpassing loveliness.  The Doorway of the Old Stone House Showing the Cathedral Window Service had begun in the Old North when the hush of the darkened church was gently broken by the rustle of a silken skirt and the bridegroom and his lady appeared. Down the aisle they came, observed by all the eager watchers. She indeed fulfilled the rumors of her grace. He, his tall figure clad in the famous military coat of blue, with its vivid scarlet lining and with his face alight with pride, looked every inch the "king" his name proclaimed him. The young couple took their places in the pew and divine service was begun. But following it, on the church green, the ladies and gentlemen, leaders in the social and civic life of Bath, welcomed Mrs. King to the place of leader, which she filled so graciously until her death. At the time of his marriage, William King still retained his business interests and home in Topsham. But as his ship-building trade had increased and his political importance had enlarged, he had built for himself an imposing homestead in Bath, where he could superintend from his own grounds the construction and sailing of his ships along the Kennebec. He was as well known in Bath society the last few years of the eighteenth century as he was in the home village of Topsham and was living a greater part of the time in that community. In 1800, shortly after his marriage, he moved to Bath with his bride to make of the mansion there a permanent home. From the very beginning of his connection with state and national affairs, King had always been a soldier. But it was during the War of 1812, that his services for Maine brought him into military prominence. His correspondence with the war department was voluminous and to him was entrusted the safeguarding of the Maine coast in such sections as it was feared the English might land. War duties took him, now General King, back to his childhood home at Dunstan Landing for the first time since he had left it as a boy leading his steers. Here the danger from the British was most feared and the intrepid leader of the Maine troops was called upon from every side to defend the homes of his native town. It was at this time, so one of the favorite legends of Saco tells, that the doughty old saw mill owner who had treated young King with scant courtesy back in 1785 when he was a raw country lad, learning his trade, now came to him, a quarter century later, and besought him for old times' sake, to protect the property of his former master. That King with a royal forgetfulness of personal injury, did all in his power for this man as for others, is never questioned. The years following the War of 1812, were again full of political strife for General King. In the Massachusetts legislature he put up a vigorous fight for the separation of Maine from the mother state. His forceful personality and his marked eloquence undoubtedly did much to support this cause. In 1820, when Maine became a Commonwealth in its own right, King was a prominent member of the body that formulated the State constitution, and his personal genius is responsible for some of its leading articles. His attitude toward prohibition soon brought him into difficulty, for Maine, even from its earliest history, has conspicuously concerned itself with the liquor question. He was not a drinking man, as such things were rated in 1800, but wine was ever served upon his table. He believed in temperance, but not in prohibition. Various quaint stories of his testy humor remain to emphasize his views. It seems that once he was entertaining a famous general from out of the state, and in due course during the dinner, wine was passed. "I never drink," was the reply to this courtesy. Later when melons were served at dessert, Gen. King poured wine upon his fruit and his guest did likewise. King said nothing, but the incident was not forgotten by him. It chanced that a few days later a judge, living in Bath, was a guest at the King mansion. When wine was proffered him, the judge refused. "Will you have it served with a spoon?" testily inquired his host. "A fortnight ago, General Blank refused to drink any of my wine but ate it with a teaspoon." At the first state election in 1820, General King was the one natural candidate for the office of governor. His election was practically unanimous. Everyone in Maine knew him. His personal history was a public record; his political life was an open book that any might read, while his universal popularity was almost phenomenal. Fur one year he served Maine as her first magistrate. The governor and his lady were a royal pair and in the old King mansion where the Bath customs house now stands, many of the nation's greatest men found hospitality. Though entirely successful in politics, in trade, and in his home life, Gov. King found not so much harmony in the church. His troubles there were continuous as his views were far too liberal for the orthodoxy of early Maine. The card parties of a Sunday afternoon, at the big house, were a source of never-ending controversy between him and the ministry. Often it was the custom of the governor, strolling home from afternoon service, to invite a group of intimates to the big house for a hand at whist. In the long parlor of the King mansion, with the breeze from the Kennebec blowing gently through the room, many a gathering of this nature passed a quiet Sabbath afternoon. The old governor was passionately fond of the game and would clap the cards down upon the table with a thund'rous noise. But never was be known to forget to be the perfect host, and always there was wine for the gentlemen and tea for the ladies. After the cards were put away, the huge old coach of the Kings would be called forth and the guests would be whirled away through the summer twilight behind the governor's own fast horses. Some worthy of the Old North church, considering it his sacred duty to remonstrate with the governor over his evil ways, took him to task with the remark: "Card playing means cheating. I could never refrain from it if perchance I were to play." Quick as a flash the retort came from Gen. King, whose temper never was of the finest: "I dare say this is true. But have no fear for me. I never allow myself to play in such company as yours." Matters went from bad to worse until the governor in a rage severed his connections with the Old North and with a sudden shifting of course, joined the rival organization of the Old South. He tried in vain to induce his wife to join him, with the highly characteristic though rather profane remark: "Jine, Nancy, jine! Good God! Ain't you as good as I am?" His argument seems not to have greatly affected Mrs. King as no record of her attendance at the Old South has ever been found. Later, the governor again had religious difficulties and returned to his allegiance at the Old North Church. "It's about like this," said his Excellency. "Once there was an obliging young chap of a woodchuck who had dug a hole for his winter home and had stored it full of nuts and good things for his winter's food. The storms came on and it was bitterly cold, but Mr. Woodchuck was comfortable in his warm bed. "A shiftless devil of a skunk came along, whining in the cold and asked to be let in. Little Woodchuck opened his door and gave him hearty welcome. "Well, Skunk got warm and time came when he should have thanked his host and left. But he didn't. He stayed and stayed and ate the Woodchuck's food and slept in the Woodchuck's bed. Then by and by he began to smell like a skunk and pretty soon things got so bad that Mr. Woodchuck had to move out. "Then Mr. Skunk settled himself for a long sleep in the warm shelter the Woodchuck had made, while poor Woodchuck had to live out the winter as best he could in the cold and snow. "Now that's about the way it was with me and the church." In 1821, at the call of President Munroe, Governor King refused renomination as governor of Maine and accepted a place on the commission appointed to investigate the Florida claims of the United States. Though at the time he won much adverse criticism by his act from Maine people who felt he should have continued to serve his own state rather than turn to federal affairs, Gov. King gained much distinction for his work on the commission. With other notable qualities the stern old governor had a keen wit and sense of humor. While on his government mission concerning the Florida Treaty in 1821, he was walking with another distinguished gentleman, through the streets of a North Carolina town. His splendid figure attracted the admiration of two girls who persisted in following the general and his companion. The men turned down a side street but the girls still pursued. At last the patience of William King, short at best, was exhausted, and turning abruptly, he remarked: "Ladies, I assure you, we are not members of Congress." Needless to say, the general and his companion continued their walk without further embarrassment. Toward the last of his life, the mind of the splendid old governor lost much of its brilliancy and his later years are clouded with poor health, enfeebled intellect and a long series of domestic sorrows, which were ended for him only at his death. It was on July 17, 1852, at the age of 85 years, that William King passed away in his old home city of Bath. The state, in recognition of his services to her, has erected an imposing granite shaft which marks the resting place of one of Maine's greatest sons. A visit to Bath discloses much of interest to the sight-seer, interested in the life of Maine's first governor. The old mansion by the Kennebec is now the site of King Tavern, while a few miles from the business section of the town, a quaint old stone house, with tall cathedral windows and with the gay garden and spreading trees of an olden time, is still standing, just as it was when Governor King and his lady so royally welcomed guests to the summer home. Note: Erastus Cunningham of Edgecomb, 89 years old, is one of the few men living who attended the funeral of Gov. King. Mr. Cunningham was made a Master Mason soon after he attained his majority. He was raised to the third degree in the lodge at Wiscasset. In his capacity as a Mason he attended the funeral of Governor William King at Bath, said funeral being, to quote Mr. Cunningham, religious, civic, Masonic and also under the auspices of the State. To hear Mr. Cunningham tell this story, as we heard it on the porch of the grocery store and post-office at Edgecomb on a Saturday in late August of 1916, one would think they buried the old governor about six times. We tried to obtain from this very old man some personal memories of this funeral, but we found they were very scant. He remembered that it took all day, but he could not remember the year or the time of the year, or any of the incidents. Mr. Cunningham has perfectly good hearing; fairly good eyesight, though he says it is failing; a perfect understanding of current affairs; and is a consistent, unfailing, prompt, and unregenerate democrat. "I never voted anything but the democratic ticket," said he, "and I don't never intend to." A. G. S. |