| Web

and Book design,

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2009 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

(HOME)

|

Under Jackson's Cloak; or the

Sawyer's Inheritance

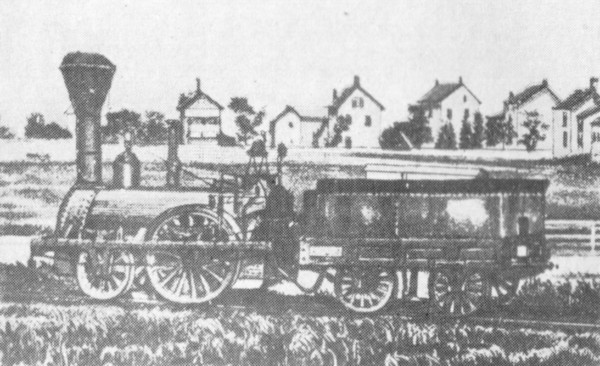

By MRS. HARRY DELBERT SMART SEVENTY miles up from the Maine coast it lay, this little village of Stillwater, lush green gardens dotting it, meadows and billowing hills of pasture land encircling it richly, then melting into the hardwood and evergreen of the great forests beyond. Westward from the Penobscot, Stillwater River divided the village, belying its name as it threshed noisily over falls and through mill races and then, remembering to whisper softly under clumps of elms and willows, crept beneath the rustic bridges and sang past lawns and gardens. And at the end, its work accomplished, the fair stream slipped gently into the embrace of the broad Penobscot. Cleanly sawed boards in huge heaps of sunny brown hugged close to the Stillwater edge mirrored in its blue. Tall, clear spars clambered tier above tier as if striving to peep farther down the Penobscot in search of shipping, well knowing they held the destiny of broad canvases of many nations, for when the vessels put out from the Maine coast, their sails set toward foreign seas, great loads of lumber filled their holds, and only when in a quarter circle of the globe they had traded this for cargoes at twenty ports did they turn their weary prows homeward, to be met at last with much rejoicing as wanderers of hazard. Across Stillwater River a low, weather-stained building, peeping from among huge elms, rejoiced in the name of the Cradle of Liberty. Gay ribands and Sunday coats drifted up its aisles, decorous Bible classes met for gossip and instruction, and under the well-smoked ceiling spirited discussions arose sometimes upon the Lyceum Question, or more often voices grew hoarse upon the imperious topics of the day. Andrew Jackson's broad garment of state-craft had slipped to the meager shoulders of Van Buren, wrapping them in heavy folds 'broidered with disaster. It was a year of vast import, this year of 1836. The National Bank reeled drunkenly beneath repeated withdrawal assaults. States' Banks sprang up luxuriant as mushrooms and with as little real substance. To secure the needed treasury ballast States' lands were offered for sale. A wave of speculation swept the country; fortunes grew from promissory notes; men were named after their holdings; finance drowned itself in a mad wassail. A tidal wave from the breaking surge came rolling in upon little Stillwater. The steps of the Cradle had gathered its nucleus of the wealth of the town, the setting sun lay broadly over eager faces. A tall man was speaking with a diplomatic drawl: "'Taint like land out west, 'n yer can't expect ter find cities there, but ef it's lumber yer wantin' I've got stumpage." "What's that No. 6?" Township No. 6 was a strip of land up the East Branch and proved a salient title for its owner. "It's this way, Grindstone, you'n Webster Plantation are nigher and cost less fer toting, but me'n Suncook have never seen an axe, we're surely in fer white-water drivin' beyond the blazes — with timber. Sawyer hez my contract fer a million." "Haint' got any more ter sell off'n yours, hey ye? Must be good ef Sawyer's in it." Rigby sat up jerkily. "Thought he took of Winslow." A soft breeze from the river brought the sound of fallen gang-gates, the mill-crew call for supper which served for all the town. Among the goodly houses of lumbering and shipping owners was the home of Enos Sawyer, with its lawns and gardens. The wide kitchen brooded over many children, warmed by the huge, cordial fireplace, and fed from the contents of the mysterious, craterous brick oven, ever redolent of past feasts and hankering for the fat geese, haunches of venison and choice spare-ribs its ravenous interior could reduce to the savoriness of the flesh pots of Egypt. "Art all alone, Grandma? Where is General Veasie? The engine is nigh about ready." It was a boyish leap through the window open to the breath of the bland, Indian Summer day, but William Burlingame was deferential enough standing before the old dame, who, gazing out across the river, seemed to have peopled the sunny morning with the ghosts of other years. A reluctant glance met his. "Sit you down, William, you're that tall my eyes get tired looking up so far. Is it the locomotive you are all mad about that brings you? Keep clear of its path, William, for it hath an eye like destruction." Deep age-lines that had cut through the fine contour of her features could not rob them of their lofty expression. Her glance wandered to the damask-spread table across the room, dainty with old silver and china. "It isn't far to see it start, Grandma," William's voice was persuasive. "Of what use?" her hand caressed a dark, inlaid cabinet upon her knee, "I have lived past my day these many years. It were sacrilege that I peep farther into the future. I would people it with splendors from the past, William; they are the heritage of my; the Mayflower carried many a scion of a noble family on its voyage of destiny. Courts and palaces were as ashes upon the bps to the adventurous spirit of these daring men — and it was thus with John Sawyer. The wide stormy sea — the wilderness — the great, new world, all opened arms to him from out the gates of the sunset. His spirit still lives, William. And it is a grand heritage waiting across the water — kings and princes showered favors upon the Sawyers, here are their tokens, the grant of Cape Elizabeth, the records of gold in the Bank of England, and even The ducal coronet. Our Almira must have her own.  "The papers lie in this cabinet, William. She are the circle of my life — free my hands that I may rest" She gazed with unseeing eyes at the freshly kindled log on the hearth and a bitter impotency grew in the strong face. "None seem to know, or care" her lips shook with a hard breath, "It lies with you, William — " Her voice was lost in the lilt of a song coming across thereat parlor. Welcome shone in the eyes of the two. Nigh a century is far seeing to recall a young man's personality transfigured in his granddaughter, but the carriage, the gold in the curls, the blue of the eyes were very like and the old dame smiled at the craft of two generations. And now the town's people had gathered beside the car track men and maidens, old and young. Their cries reached the kitchen: "She will never start, never — never!" "She has — she does! 'Rah! 'rah!" "Ho, she has tripped! Pick up your feet, Monster!" "A stop, a stop! Ha, ha, stuck!" A wave of derision filled the valley. "Fools and their money, Mose Greenleaf! Fools and their money, Sam Veasie!" The last cry silenced itself in suspense; slowly, surely, the baffled mechanism ground along, grumbling, shrilling, around a curve gone. It was a proud toast pledged across the wreckage of Thanksgiving feasting in Enos Sawyer's kitchen, and a genial host makes keen wits, it is said. This one may have known, for his flagons held somewhat of the contents of the hold of his brother's brig, "Lightfoot," since the sunny slopes of the Argonne lie in the route of trade with the looms of India. Certain it is the momentous day of November, 1836, slipped out bland and smiling as if with regrets that it must leave that gracious atmosphere of congratulation, and in the dusk Grandma Sawyer was saying softly as to a visible presence, "An' it were stately banqueting halls your Almira were fitting, Enos — it is a splendid heritage." Taverns did a thrifty business along the wood's trail of the Penobscot, their homely fare and rough beds a haven to the weary men and beasts on that far trail. Up beyond the way houses many a camp crouched back in the woods, sweet with balsamy fir and within sound of logging bells and rippling waters, and even the ring of steel mingled with the deep boom of falling trees. It was the last month of the year, clear and mild. The Matawan Trail was guided by a new blaze high above the fallen leaves. Here choppers, limbers and swampers followed each the other among the trees, ever in the three bands, and whether in the eager strength of morning or the lag of noon or night time a frequent call came for the number of trees between, sometimes in jest, but always with that bit of feeling that cut in the pride of the woodsman. It came out clearly now in the lusty shout: "Close up, close up, Willie Michels!" the cry was a challenge. " That's it! There you are, ha, ha! Now at his heels! Ho, there, Kinkade! Treed — treed by a curly-haired lad in his teens! Walk up and take an axe bit, Willie!" The ringing mockery deafened the chopper to another and sharper cry: "It cracks, my God, it is going — Willie, Oh, Willie!" They cut away the branches frantically, even Kinkade, the fierce fire in his eyes gone out. The afternoon sky showed brilliantly blue, the sunshine lay on a still form, a lad's curls holding its glory there above a deep splotch in the temple. Men with caps hanging from tense hands stood by, a yoke of oxen hitched to a team drag waited patiently. Back in the woods a sound of chopping trembled on the air with a driver's distant call, a bluejay trilled out vibrantly and under the leafless December branches panting, boyish lips grew still. A sound of hoofs beat earth and air as a rider cantered into view among the trees. He knew the meaning of that stricken, potential group, in a moment was kneeling on the sear leaves. None saw the curtain of blue slip out from the sky, nor a gray-white bank fill in the northwest; a wolf's far cry quivered in the slow rustle of the wind down the valley, growing more and more potent, harassing the softness of the air; an ox lowed uneasily as the sun dropped into the gray smother, and another wolf call was answered as though a scent lay lightly on the air. The man beside the lad arose — it was Sawyer, his stern face grieving. "I shall start for home with him to-morrow; tell Shannon to make ready." But the morrow wakened to a white waste of snow, earth and air one confusing element. Men and teams were glad of shelter. Dawn followed dark in a gray march, the drifts piling up and up. It was only when half-light and dusk had counted off five days that the sun shone out and a little band issued forth from the camp; they made a bed for Willie Michels under the century-old pines and set a wide, green slab, deeply scored with his name, at its head. Down in Stillwater his mother grieved, grieved sadly, but understood. It was only one of the many tragedies beyond the blaze. *

* *

The bitter night nipped sharply at travelers abroad, but within the great parlor a keen blaze had crumbled so many logs in magic transformation that an atmosphere of benignant summertime lay over the logger in his arm chair by the fireside, and even in the far corner over the dark, old loom against which William Burlingame leaned lightly. There his dark eyes and locks were in sharp contrast with the fairness of the girl at her work. In other nooks a medley of yellow heads and brown located rippling, subdued voices, knitting needles clicked rythmically, the presence of a mother made itself felt, and in the cosiest corner of the hearth, grandma, in her deep rocker, rested her hands in a gleam of ebony beneath them. "Could you make use of another man up the Trail, Mr. Sawyer, to take Willie Michel's place?" The lathe of the loom ceased to swing. "I could were he a man. What could you do with the hands of a woman? Strong work lies up the Matawan Trail." A quick color arose in the face of the two by the loom, the steady resolve in Burlingame's eyes grew. "I'll not disappoint you." And now Sawyer swung his chair to face the corner in time to catch a quick shaft of sympathy not intended for him. The treadles bent with the rapid shift while the bright shuttle slipped between the threads on a swift errand and the reed beat up the pattern of fine linen. "I have to send two yoke of oxen, loaded, and drifts are nearer than camp, besides," hesitating, his keen eyes on Burlingame's face, "Rigby said the wolves closed up on his team so he had to shoot." The room seemed strangely still for a minute. Sawyer laughed shortly. "Know your way across Matawan Lake if it snows?" "I have been across." "Make Watson's place first night — ten good days ought to find you at the lake. May get there in time to send a team across. "That you, Winslow?" as the outer door swung back to admit a tall, stooped figure. "That's me, Sawyer. Heerd yer was down an' 'hero' int-rusted in loggin' — Haow's my town's timber turning out, man?" He drew a chair close to the logger. "Proper style, Winslow, proud deal that, proud deal!" "How's the Cradle nowadays? Changed your mind on the Mexican Policy?" "No, no. Not 'less Rigby has. Can't agree with him. Ef he's fer, I'm agin'." "Right or wrong?" "Right! I'm right which ever. Only need him ter reg'late by. Heerd frum Lish, yer say? Kent's darter, Victory, like ter slip under William's crown — he that low? The long journey comes to us all — mebby he's done his share of mischief so quick — poor man! Gladstun refused a peerage!" "Aye; and O'Connell sits for Ireland in the Imperial Parliament before Emancipation has given him the right of candidature. Now Ireland stands; and there is a man for you! What's the world comin' to with trouble brewin' in India. Guess I'll stay home and keep store." What was that vibrant tone in her son's voice? Grandma stooped toward him with intent eyes. Had a long silent chord responded, after generations, to the old-world cry for his birthright? Before the aged vision a vista opened. It was adorned with a splendid brocade woven of cloth-of-gold and the people who walked were courtiers for this highway was the highway of the King. The space between mother and son changed — took on form and seeming. She heard his incisive voice in the halls of Parliament, the steady eye, steely blue with unwavering purpose, and her words came brokenly in breath too soft for sound. "Ah, William! You may have a master hand at the stylus in tracing life scrolls, and Almira — " The huge forestick lurched between the andirons burned through its middle, the blaze snapping and flaring up the flue. Winslow had gone, there was a sound of mother and children on the broad staircase, and in the far corner the now silent loom shrank farther back into the shadows that enveloped the two in the deep window-seat. "Think you these months you are to lose will not put you at the foot of your class, lad?" The girl's words and tone did not fit her smile hidden in the gloom, "then what would become of Grandma's Legacy you promised me for a dowery against the time when my Knight should come riding by — " "Knight and Legacy are both pledged, Madam," bowing in mock humility, "and as for lessons, they are a sweet breath. It is your father who is the dragon in my road," ruefully. "I look up to him an he were a planet." "And his daughter, Sir!" "I have not his permission to say — but she is dear to me past telling." In the dusk Almira's lashes fell. Sawyer turned his eyes from the heaped coals and the two brands smoking in the corners of the hearth to the dark, old cabinet in grandma's lap. Was he seeing with a man's clear vision and did the broad lands, even the ducal coronet and cloak of scarlet with all they implied find favor at last, or did they still lie like ashes on the lips — the new world hold with its appeal. Long before daybreak the light from the kitchen flooded the yard as hoofs crunched and creaked in the crisply packed snow. The door closed sharply and the colt sped up the road taking sight and sound of logger and sleigh bells out of ken and leaving only the silent oxen with loaded sleds, dim in the shadows. "You will wait for father at the lake, William?" Almira dropped the toaster, her face flushed by the open fire. "And the wolves — are you not afraid? They are sore hungry now the snow is so deep." William's face was anxious. "I'm not afraid — of wolves, but Greek and Latin does not make for logging." "Then why do you log if your talents lie not that way?" "It is the measure of a man to a logger and holds no hardship aside from failure. Your father hath a grasp of that business beyond my knowing. I would not be a humiliation to either of you." The lad's face betrayed the stress of his emotions. The firelight lay softly over the kitchen with its warmth and brightness, the daintily spread table, the high-backed rockers, rich chests of drawers and broad dressers reflecting in polished tops the cunning of potter and fineness of clay. It rested as tenderly on two figures by the hearth. A softness crept into the girl's eyes raised in reply. "You could not be that, William, it surely is beyond your knowing. You will do us all proud in the story of grandma's box." "Your tongue hath a convincing quality, Madam, and your will is — my law." *

* *

Laced with black branches, the deep-hollowed road stretched on and on under the low-dropping moon, the hoar frost silvered tree trail, then the delicate flush of gray dawn grew into gold and, in the lee of a clump of firs, a splendid purple light quivered and changed like a thing of life. Was there an indescribable presence lurking in the shadows of the tall pines, blowing its weird harp in vanishing music, filling the vast reaches of hardwood growth and deep evergreen coppices with the call of the wild? Cold, rain and snow wrapped the woods trail in turn, or mingled. It was a long way to fare for the woods road slid off or sank into slushy pools, the downpour drenching all abroad while a pale mist from the river fluttered like diaphanous drapery among the bare, mossy, seeping trunks; and now Lake Matawan lay before the traveler in a great sheet of ice, dark as water for the most part, but in places beat up into a fluff of treacherous honeycomb, in wavering, shelly rifts. A far search with hand-shielded eyes revealed a horse and sleigh zigzaging across the darkened lake. A fox barked shrilly among the dun flowage on the north shore and a sharp wind parted the gray drift to let a splendid shaft of sunset turn to jewels that sudden frost shower. The colt drew up, fretting and stamping. Sawyer busied himself inspecting the loads beneath the great sail-cloth. "Hard trip?" he asked, turning to Burlingame. "Ordinary, I guess." William stepped beside the leaders and swung his goad. "I got chilly driving, wind is keen. You may take my place for a while," with a kindly glance. "You've tramped a bit of a way. Tell me about it when we get to bunk." The tall, lean frame of the lumberman swung out over the ice in great strides; the weary, sluggish oxen, responding to a master's voice and touch, set out briskly. Wadleigh took the other team and Kinkade drew the rein over the colt. William tucked himself among the robes, his frozen slicker keeping out the wind. Then, free to look about him, he saw the heavy sled glide out over the ice, saw the old lumberman in the lead and Wadleigh closing up behind. Suddenly he straightened. "Why don't they separate if the ice is dangerous?" "Better ask Sawyer, guess he thinks he's boss here," with a laugh at the sharp demand. "Might be int'rusting ter hear his views." "I care not what you say!" William's voice was tense and angry. "Drive within hail, Kinkade, that will not implicate you!" The man smiled patronizingly. "I'll trust Sawyer with what's his'n" — and even as he spoke the great logging sleds slipped out into the night. Powerless but unconvinced, the young man strained his vision in the dusk. Only the sound of team bells rang back, mingling with chimes from the sleigh. Warmed from the cold, his muscles relaxed after the long journey, William drowsed at intervals, but ever caught himself listening, searching the night and listening. The horse was going at a walk, Kinkade finding it advisable, often, to take the lead and try the ice in order to avoid rifts; the hours seemed a strange, uncanny age. They were nearing the head of the lake when a sound, as of a cannon, boomed across the darkness. The ice beneath the sleigh shivered with the shock that sent the colt on her haunches. "It's that — they've broken through!" William seized the reins from Kinkade's trembling hands. "You don't mean —?" weakly trying to ward off positive assurance. "We must find them," the lad wheeled the horse sharply in the darkness. "Easy, now!" Kinkade snatched at the lines, "you'll have us under water, too. There's chance in this lake to sink an army. Lord, man! have a care," but a struggling mass came into view and William sprang from the sleigh flinging the lines to Kinkade. "Drive for men, tackle and blankets, and drive — drive!" It was a frightful mass in the black water — the heavy splash of the oxen and those horrible, groaning breaths. In the light of the lantern four black heads still arose above the surface. Sawyer and Wadleigh held, with desperate strength, to a line of rigging attached to an ox yoke, grimly battling to keep the brutes' heads above the water. Running steps and a flare of the lantern on the ice at his feet assured Sawyer of Burlingame's proximity. "Take my place, lad, and use your strength. The tongue must be cut to loose the sleds or they go down." William saw the dark shape of the man creeping farther and farther out over the shivering ice, hugging flat; heard the axe fall heavily with the hampered blow and clung with chilling hands to the fast freezing rope. The heavy axe plunged surely again and again. He thought a distant chime of bells was growing nearer, the wind pierced him, the dark closed around, but the circle of the lantern's rays outlined the jagged ice and the black water with the helpless beasts struggling in its depths — another plash and the axe had ceased to work. William held his breath listening. There was no sound. He threw the rope to Wadleigh and grasping the sled tongue slid down, was between the laboring oxen. A body washed heavily against him, thrust by the heaving of the animal on his right as the water surged with its stroke. Was Sawyer stunned? He lay heavy and inert in the boy's grasp. Drowning men grapple. Many lights blinded the lad, voices shouted and a rope end fell by his face. Mechanically the line knotted in his fingers about the motionless body, and, loosed of the weight, his knees tried weakly to follow his hands in the climb up the sled tongue, but the humming in his ears grew past endurance. Such a heap of logs piled, cross-piled, with red, reeking tongues of flame creeping with a whirring sound through the interstices, rising in a united flame up and up. William watched it wearily, not caring to think. Presently the log walls about him took shape, and he wondered if stars were peeping down the opening through which the smoke arose in volumes, voices came as from a distance. "Poor lad, he's about out. It was a grand plunge — quick hands and a clear thinkin' — it is life Sawyer owes him." *

* *

Red dawn crept in at last, its ruddiness promising hopefully. Sawyer and Burlingame saw its light as from out a great blank. With the return of consciousness came knowledge of the stress of business and from his bed the logger gave orders to his crews. The weeks slipped by with every man at his post as spring drew near, the freezing at night lasted but through the hours of morning, and now the under-thaw was sapping even the main roads. Breakfasts were served at midnight and empty sleds came to camp over the slush of noontime. It was a good fight and winning, but the cough and chills which followed the plunge in the lake grew rather than lessened and Sawyer remained in camp. "You'd better git home on the snow," Shannon cautioned him, "you've had 'bout enough for one winter 'n I can handle all here now — hey Burlingame take ye." Despite the cough and weakness every man in camp was surprised to see Sawyer quit the woods before the last stick of timber was on the lake and perhaps none were more so than Sawyer himself. "I don't understand it!" he muttered again and again on the Trail, "but I must get home — home." *

* *

Burlingame threaded a strand of linen through the harness of the loom and tendered it to Almira for drawing in the reed. "It was grand what you did, William. You know father never says much, but he holds you what — you are." "And what may that be?" "An awkward lad if you upset the baskets and tangle the web." "Lad! When shall I be a man, Miss?" "It is a long journey, William, and does not lie in years away." Through that strange spring the last of the logs were dragged over made roads, and the ice broke up in the lakes leaving a clear line to the sea by the middle of April. Back at the landing the Matawan boss was ready with men and tackle for booming the lakes and now great fires were kindled all along the river. Boat crews separated each logger's cut, the men working day and night for the river never slept and there was no other chance to catch the logs for sorting. A sharp change of temperature chilled the rain to snow that beat in the faces of the drivers, icing the log marks past recognizing. Clothing was soaked and then frozen, a slip on the icy logs might mean life pounded out by the oncoming drive. Many logs drifted out to sea; others, lodged by a rapid fall of water, choked the streams. Summer came. The great financial panic of 1837 was permeating every branch of industry. Money that had been issued by national and state banks came in already repudiated; metal had paid for the importation of luxuries from across the water; the country was without hard money save for that one foresight of Andrew Jackson which required that public lands be paid for in gold and silver, and even these had changed hands so many times that their present holders had given script to men who had themselves given script. This paper was now due. Men, who had paid hard money for chimerical western cities giving paper for a part loan, were swept off their feet to meet panic stricken demands. In Stillwater many stores were closed till lumbering settlements could be made. Mills had ceased to work and the river was filled with logs waiting to be sawed, but with no money to pay workmen. A silence fell over the little village. Men lounged about in groups, talking abolition and the last battle with the Seminoles, then went home with empty hands to empty cupboards.

Winslow had closed his store with the rest, remarking: "They all want to pay paper fer oorn'n tea, an' wholesalers wunt take it. I can't feed all Stillwater," jingling the few coins in his pockets. "Is it because my stumpage hasn't been settled, that you do this?" Sawyer asked from the hearth rug of his parlor. His lean frame was thin to emaciation now and a restless weariness was in his movements, a great pity and impatience lay in the deep eyes. "No, no, Sawyer! No hurry. I'm hevin' my little corn mush, n bem' mush 'stead of loaves and fishes it mount boil the kittle fer all Stillwater. Keep you quiet when yer gold comes in an' I'll bury it in an iron pot like Captain Kidd did. It'll be safer thet way — guess we all would be," chuckling grimly. His eyes met Sawyer's and winced as from a thrust. "Mebby you hed better git inter business. Better look inter yer affairs," rising jerkily. "When Lish comes. I'm tired, Winslow; and it won't be a lad's work to do everything that needs reckoning these days." Winslow's suggestion was repeated by many men, but always elicited the same reply. "When Lish comes I'll settle. I'm tired now." *

* *

Summer slipped by and the great oxen, that had been rescued from the lake, grazed with others on the sunny pasture slopes, fruit came in its season, but gardens and plowed fields flourished weeds instead of grain, and the pinch of want crept into homes that had known only plenty. Then, one day, Enos Sawyer slipped out very quietly. Men, hearing of his going, came from far and near for he had dipped deep in business and finance, and they laid him away — a comrade in the work of the world. And now his paper began coming in. While the man, himself, sat by the fire or looked from his door, confidence had remained unshaken for it was a clear eye and able hand in control, but now he was gone. "I can't git over it," Winslow grumbled. "Let's see! Was that stumpage settled?" Rigby quizzed. Winslow eyed the man from head to foot, his lean, stooped figure almost straightening itself. "All men don't hey jackal thoughts, Art Rigby. Him that's gone was a man." The mother of the bereft family, Clarissa Sawyer, now broken and worn, searched for records, tried to recollect the few words her reserved husband had spoken on business, turned a face of unswerving faith and patience to all. "You shall have what is yours. He would want it should be so," was ever on her lips. Gradually the work slipped into William's hands. He had been with Sawyer and in his confidence as much as any. Records were turned over and over again and again to no purpose. The fabric Sawyer had built, sapped here and there by paper money and dishonesty, crumbled. The National Bank may have had his gold. Biddle never admitted it — and there was but one result of such inquiry. Anxious and distraught Burlingame came into the Sawyer parlor. A September glory of warmth and color lay over the room, goldenrod heaped the hearth, apples red as wine filled a basket on the table, while asters in delicate shades leaned out over the mantle vases. The spindle and loom grew quiet. It was this they had waited for through the long days. Words were slow in coming. "You will have this house and lot — " He missed the shriek of saws down the river perhaps for the first time, his lips getting stiff. Across the river the Cradle of Liberty must be humming with recitations. The children were gone from kitchen and parlor, even Enos and little Mahalah. He turned from the window and lifted his face to the three women. " — That is about all." The mother of the brood stepped into the kitchen with a brisk word and the door closed. Grandma slipped up to her room closely clasping the dark box and whispering: "The crest has the strawberry leaves — that is a duchy, and the falcon — Ah, William! You will heed now, and my Almira — " In the long parlor William sat down weakly, his head in his hands. Had he done his best — if he knew — if he but knew! It was such a bitter ending and they had trusted him. The sunshine mocked his baffled desire for service. Of what use was the good work he had done in his books? What need to go on? And now through the confused irritation of his mind came a shaft of light. Perhaps Grandmother's Legacy had a real working basis even for his mind. He would empty the inlaid box of its contents, work out the long line of heredity and, then if it might be, lay the title to lands and gold, even the ermine and crest at the feet of its rightful inheritor. He saw the girl regally clothed, her fair face shining out like a star. Saw, among courtiers, the hand that had plied the shuttle, bearing the silver rod of her estate. Wooing and betrothal flashed out in the picture and the brows of the thinker got damp in his hands, the breath of his lips hurt; there was a princely wedding and the old line proudly made its offering of brave sons and fair daughters who, equally loyal, should perpetuate — in love and honor. William Burlingame stood up and the familiar room, mellowed in sunshine; the dark, old loom; the spinning wheel; even the fresh tufts of goldenrod on the hearth had a look of unreality of the frame of a picture with a blank in the place of a dear, accustomed face. He was seeing the girl half the distance of the room away, realizing how much wider that distance must grow by his own efforts only, for the blue eyes were meeting his full of understanding for his recent defeat. As he gazed a shyness crept into the imperious face, the glance avoided his; was he only to hold this trust till another came to claim — never gather for himself? He told the girl his plan very quietly; that his resolve was made and that it but needed the records he should find to win a circlet to bind her brow. A joyous laugh brought the picture back to its setting. "A pretty romance, truly, Sweet William, but not befitting a New England maiden who hath John Sawyer for ancestor and with her knight — pledged. Or else, so it please you, she will wait till another come riding by." "You gave no pledge, Almira; I only — " And now the curls fell over the flushed face for the distance no longer lay between them. "Shall we keep it together, Almira — here?" "Aye, William." Neither of the two saw grandma at the door. She was standing with her clasped hands over her heart, an inlaid box hugged tightly beneath them; a white, set strangeness crept over her features, her eyes held a haunted darkness. A joyous call came up the river path. "Uncle Lish is home with the 'Lightfoot'!" but she heeded it not. The two young people went to meet him down the hill, and in the eyes of William Burlingame lay the trust that had become his. The chatter of school children hovering about the bronzed, old seaman reached them and they joined the happy throng. The lumber had sold well, the hold was full of stores, the lockers of gold. It had been a good voyage and this was truly a glad welcome home. The parlor door swung back to admit the gay company. Before the hearth sat grandma, white and crumpled like a bit of parchment, an empty inlaid box was open on her knee and under the scorched goldenrod between the andirons lay a heap of blackened papers.

AUTHOR'S NOTE: My authorities for my story are Sketches of Oldtown by David Norton, The Sawyer Genealogy and Family Tradition, stories of early logging I have heard and the story of the Sawyer Inheritance as told me by my great-aunt, Mrs. Alvin Lenfest, in substance as follows: The Sawyers were of English family holding a duchy, of which the strawberry leaves in the crest is the emblem. Of these Sawyers an Edmund Sawyer died, leaving no wife, children or will, and a large fortune was never administered upon (I find this latter a fact from data in our Bangor library). A grant of Cape Elizabeth to a Sawyer with papers proving titles, genealogy, etc., was supposed to be in grandma's cabinet. Grandma had been so sure that William Burlingame was to be a scholar and bring about the great desire of her life that the loss of her son's fortune made for delight, bringing the necessity of this nearer. The shock of finding that William had decided against school and therefore the probability that the claim to the inheritance never would be proved, caused her despair culminating in the destruction of the papers. |

||||